Gems and Treasures from the College of St. Scholastica Book & Media Sale, 1

The Library at the College of St. Scholastica, once a year, both weeds its collection and accepts donations (I presume from faculty and staff) for a sale. Popular reading starts at a dollar, I think — recent bestsellers. The rest starts at a quarter and slides, over a week, down to a dime, then to “free, just please take them.”

Content Warning: The following materials involve some complicated representations of indigenous cultures in Canada and the State of Washington. Some are produced in partnership with indigenous peoples, while others promise to tell the stories of a people lost to time. In any case, my hope is to look at what happens when a people control their own representation (the Japan Tourist Library), collaborate to shape their representation with their colonizers (Our Totem is the Raven), and when they lose control altogether (The Loon’s Necklace). “Looking at them” doesn’t mean I know what I think or what to say, yet.

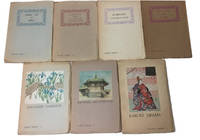

Japan Tourist Library

I picked up a few books clearly purchased in the 1970s or ’80s on a trip in Japan — from something called “the Tourist Library,” a “series of pamphlets published in the Showa period by the Board of Tourist Industry of the Japanese Government Railways, to explain important aspects of Japanese culture and national life to visitors from overseas.”

According to Wikipedia, “The Shōwa era (昭和, Shōwa) refers to the period of Japanese history corresponding to the reign of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) from December 25, 1926 until his death on January 7, 1989. The pre-1945 and post-war Shōwa periods are almost-completely different states: the pre-1945 Shōwa era (1926–1945) concerns the Empire of Japan, and post-1945 Shōwa era (1945–1989) is the State of Japan.”

So what was Japan, to tourists, in the postwar era? It was traditional — as if the State of Japan wanted to communicate that it was still the Empire of Japan, as if the second World War didn’t happen and change everything.

While these books were clearly donated by someone who had taken a trip to Japan (as they were inscribed), a lot of what I found were weeded from the library collection, including some CDs and some films — movies on film!

I like trying to learn about people from the records and the books they accumulate. So institutional cast-offs are less interesting to me, but these have some resonance. I’ll write about the compact discs in a separate post (like I wrote about other found music here and here). The films were interesting, though.

Our Totem is the Raven

I’m a kid of the seventies, so I wanted to like this, but I was wary. I was in my thirties when I discovered that the crying Indian in the anti-pollution campaign was not actually an Indian. So I was prepared to be disturbed. It’s a creature of its time — mentor stories were common (Shazam! featured a character who guided young Billy Batson specifically called Mentor).

But to call it a creature of its time is not to say it’s not valuable, and as co-produced with United Indians of All Tribes and with the Quinault Tribal Council, it’s at least a document of a community struggling to tell its story within the media and narratives of its colonizers.

The Loon’s Necklace

This one is the one that smarts, a bit, stings. The catalog text here, about this Canadian film, reads thus:

Describes the Indian legend of how the Loon received its neckband. The story is portrayed by actors wearing the authentic ceremonial masks carved by the Indians of the British Columbia coast from the collection of the National Museum of Canada …

The film begins with the following creeper: “The Story of “The Loon’s Necklace” is based on an Indian legend. No one knows when the legend was first told, but it was long before the white man came to the British Columbia Coast … This film grew out of a visit to the National Museum of Canada and discussions with Dr. Douglas Leechman, the archaeologist there. The masks used are from the Museum’s collection, and though they were carved many years ago the colours have not been retouched.

“In presenting, ‘The Loon’s Necklace’ The Canadian Education Association commends to all the rich inheritance of our country which awaits the visitor in our museums.” The film concludes with the following creeper: “This film was made available to the Canadian Education Association for showings in Canada through the courtesy of Imperial Oil Limited.”

This film won the inaugural Canadian Film Award for Film of the Year in 1949. It’s as enchanting an example of film-making as it is wrong-headed in its representation of indigenous peoples as almost mythically lost to time. It seems mostly to exist to validate the collection of artifacts and masks in the museum. (And don’t get me started about the odd sponsorship of Imperial Oil — intended as philanthropic and yet with the potential unintended consequence of weakening contemporary indigenous claims to land and environmental rights.)

I wish I had some thesis about representation and communities, from these three artifacts. I don’t. I have a lot to think about, and maybe you do too.

And I have a lot to be thankful for, living in a community with so many voices telling their stories. Moira Villiard, Ivy Vainio, I appreciate your work more when I see these videos, the strength and integrity of your vision. In the first week of December, an exhibit about being Asian-American in northern Minnesota will open at Lake Superior College and at UMD by Nancy XiáoRong Valentine, a powerful voice, too. I appreciate those voices more seeing these books and films.

Anyway. A lot for me to think about. Thank you for listening.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments