PDD Geoguessr #31: Gridlock

Duluth formed from the merger of multiple smaller townships, with these townships themselves comprised of multiple different housing additions. These additions were almost always laid out on a grid, but the orientation of that grid was often effected by the often challenging elements of Duluth’s geography, such as rivers, streams, hills, and Lake Superior, as well as the existence of other grids. In the early days of Duluth, the different grid systems had gaps between them, but as the city grew, the gaps closed, resulting in some novel intersections and street patterns. This Geoguessr looks at the conflict between different grid systems in Duluth.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 required townships established after the Revolutionary War to be laid out in grids of six square miles oriented on north-south/east-west axes. For the reason’s noted above, Duluth’s topography made fulfilling this requirement challenging.

Growing up on the East Hillside, I always assumed that the streets in my neighborhood were oriented in the East/West cardinal directions. I lived on East Fifth Street after all, not Northeast Fifth Street. More than that, on the hillside, Lake Superior creates an omnipresent orientation point that overwhelms the abstraction of compass directions. The city of Duluth itself chooses this orientation toward the Lake and the St. Louis River for its official neighborhood map.

My mental map of Duluth is so fixed into this orientation that it wasn’t until putting together this post that I noticed the alignment of Woodland Avenue. I’ve always thought of it as a diagonal that cuts across the grid of the hillside but the lower part of Woodland Avenue is precisely oriented on a North-South axis. The hillside is the diagonal.

The purple line reflects two ways of visualizing Woodland Avenue and the city of Duluth as a whole (images from Google Earth)

In looking for locations for this challenge, I saw neighborhoods all across Duluth where the cardinal orientation and lake orientation came into sudden conflict. I find the most dramatic of these conflict points to be North Central Avenue, shown in the image at the top of this post. To the west (and south, of course) of this dividing line, the cardinal grid becomes the dominant guiding force more than in any other part of the city, but even here Grand Avenue cuts its way across this otherwise uniform street system before finally conforming to the compass directions by the time it turns into Commonwealth Avenue, where it reaches the unwavering North-South grids of Gary-New Duluth. And even within this nearly uniform part of the city, the entirety of Norton Park has gone counter to all the other neighborhoods and aligned itself with Grand Avenue and the St. Louis River, not the compass.

Even in areas with similar topography, throughout the city you can see different choices being made in how to align the streets — north-south orientation or lake-river orientation. These choices were made long ago and are now largely fixed. The orientation we choose for the city within our own mental maps, however, is not. While I was college, a few years before the introduction of smart phones, a guy showed up at my friend’s house somewhat intoxicated with a story of having lost something on the way over but only able to provide a somewhat vague description of where he may have lost it. I got out the physical map of the city that I generally took with me when biking and everyone in the house immediately became somewhat offended and indignant. One person explained, “We live here. We don’t need a map.” Ultimately, we found the right spot using the map, but the general mood remained one of annoyance more than appreciation. This sense of pride in wayfinding from experience strongly favors a lake orientation of the city, as the lake dominates one’s experience of the city.

Lake Superior, an orientation point that is often difficult to miss when making a turn at an intersection. (Photo by Matthew James)

But now time has passed and the appearance of a physical map would likely be treated as novelty rather than an offense. We all have access to Google maps with precise location data and real-time optimized directions that we use out of convenience as much as necessity. And nearly all new cars now have large map displays built into the dashboards. All of these devices have compass North as the default. There is no “Lake Orientation” setting. This makes me think that the North-South orientation will eventually dominate people’s mental maps. But I can’t say that with any certainty. It might be that people new to Duluth hold a north-south orientation but eventually the omnipresent lake slowly shifts their sense of the city. Or maybe people who grow up in North-South neighborhoods hold a North-South orientation and people who grew up just a few blocks away on a street oriented along the lake continue to orient themselves along the lake. For myself, I have a map based model of the city oriented to the north and a memory based model of the city oriented along the lake, and these are generally, but not always, in alignment.

This Geoguessr challenge tests your own sense of alignment. It provides five locations where the streets do not meet at orderly right angles. The locations are a bit set back from the intersections to obscure the street signs as much as possible, as that would make the challenge much less of a challenge. And to maximize the disorientation, this is a no-move challenge. Each round lasts three minutes.

How to Play Geoguessr

GeoGuessr can be played on a laptop or desktop and on Android or IoS mobile devices with the GeoGuessr app. Just click on the link that fits how you play. You can create an account to keep track of your scores and see how you compare to other players or just click on the link above to play as a guest without having to create an account or log in.

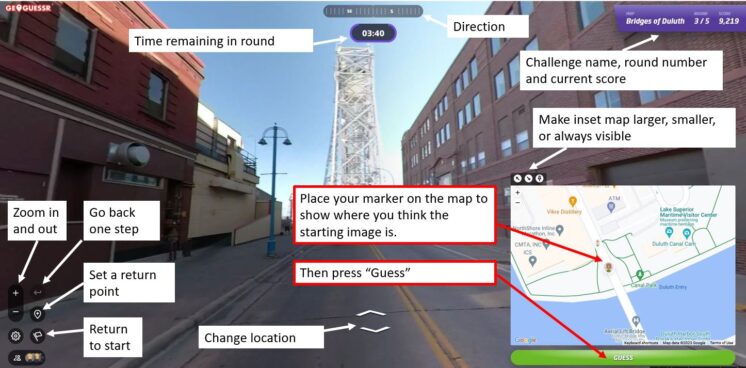

Every game consists of five locations based on a theme chosen by the game creator. You are shown a Streetview image stripped of all the informational labels that are normally overlayed onto the image. Unless the challenge specifically restricts it, you can move around and look for clues like street signs and business names to find out where you are. The image below shows a basic overview of the Geoguessr screen layout and controls.

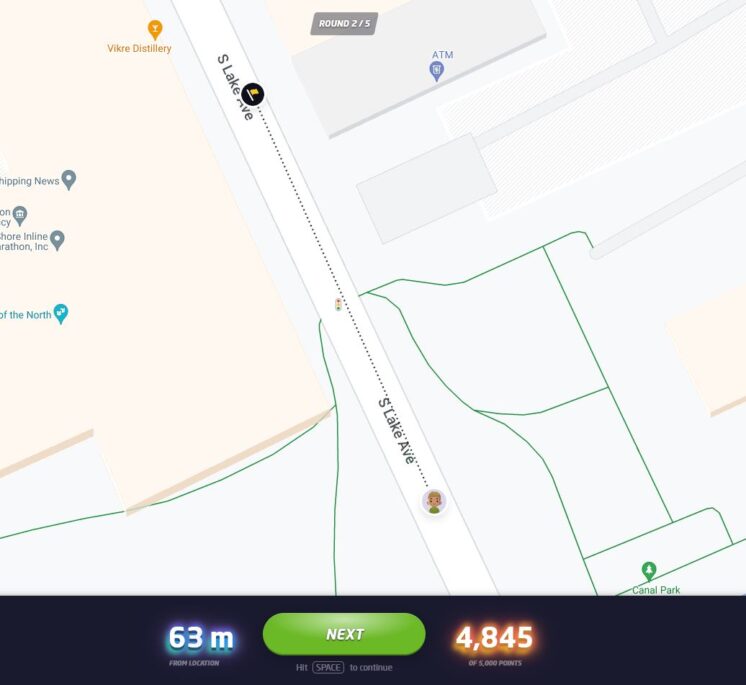

Once you think you know the location — or are nearly out of time — you use the inset map to place your marker where you believe the round started. After you hit “Guess,” you will see how close you were to the correct location and how many points your guess earned. The closer you are to the location, the higher your score, with a maximum score of 5,000 points. On a map that covers a small area, like the Gary-New Duluth neighborhood, being off by a few blocks will cost you a lot of points. On a map that has locations from around the world, you will get nearly all the points just for finding the right city. The maximum error for a perfect score also changes by map size, but in general if you are within 50 feet (15 meters) you will always get the full 5,000 points.

Not often, but every now and then, GeoGuessr gets a little buggy. If the underlying Streetview imagery has changed since the game was made, sometimes it repeats the last round, gives a black screen, or doesn’t allow a guess to be made. If that happens, please let me know and I’ll update the challenge.

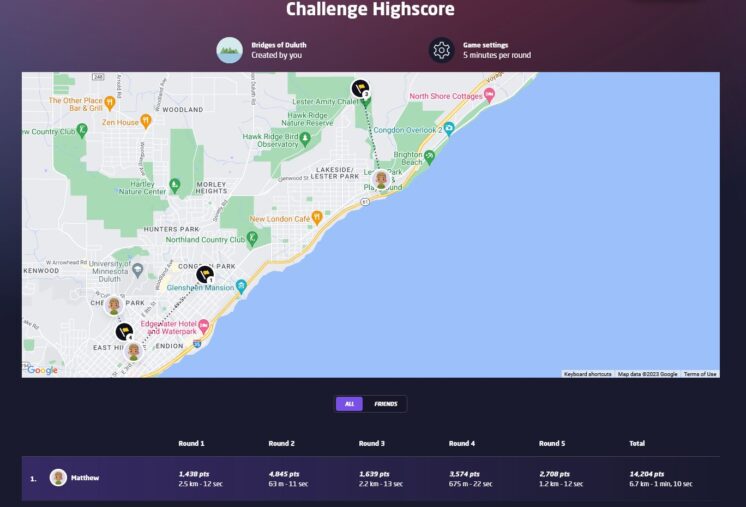

At the end of the five rounds, an overview screen shows your score for each round in addition to your guessing time and how far off you were from the correct location. The correct locations and your guesses are also shown on a map and you can click on any of the round numbers to review the locations. Additionally, the final screen in a challenge will show how you rank compared to the top scorers of the challenge. When choosing your user name, keep in mind that your user name and score per round will be visible to other players of the challenge.

If you have feedback on this challenge or ideas for future challenges, please share them in the comments below.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

1 Comment

Gina Temple-Rhodes

about 1 month ago