Avant-Garde Women: Gertrude Stein Makes No Sense

Stylistically it is appropriate to link Gertrude Stein’s experimental 1914 book Tender Buttons: Objects, Food, Rooms to Dadaism, because the book makes no sense. It pre-dates Dada’s 1916 anarchic language-destroying sound poetry, so we can’t say the Dadaists invented nonsense. Perhaps we can say the Dadaists invented “sheer nonsense.” Stein hadn’t taken it quite that far. But Tender Buttons began her mission to explore the strange new worlds of the sense/nonsense boundary.

Else Lasker-Schüler explored that same boundary in 1913, in her language-subverting experiments that also influenced Dadaism. The Dadaists paid homage to, and expanded, Lasker-Schüler’s work: her “nonsense sound poetry in Berlin cabarets, poems that would be used a few years later by the Zurich dadaists in the Cabaret Voltaire” (Baroness Elsa by Irene Gammel, pp. 146-147). Lasker-Schüler was the only woman in the inner circle of German Expressionist poetry, a Stein-esque figure in her own right who cross-dressed and ruled the Berlin nightlife. And one of her innovations was the performance of poetry that didn’t make sense.

For that reason, both she and Stein represent a proto-Dadaist spirit, even though technically Lasker-Schüler was an Expressionist and Stein was a Modernist. All the cool kids were doing it. Stein’s writing of Tender Buttons was contemporary with Lasker-Schüler’s nonsense performances, which Stein very well may have been aware of, her hyper-senses tuned to the avant-garde. Like the birth of calculus, many artists were developing similar approaches around the same time. Nonsense was in the air.

Classifying Stein as a Modernist in the vein of James Joyce and T.S. Eliot, one notes they also made little sense when they felt like it. For instance Jorge Luis Borges, one of the most literate readers of the 20th Century, said of Joyce’s Ulysses, “Let’s face it, it’s unreadable.” And as the Poetry Foundation says, Joyce’s “masterpiece of modernist writing, Ulysses, was composed after his exposure to Stein.”

In 1916, Joyce lived in Zurich while Dadaism formed there at the Cabaret Voltaire. Did he appreciate that his book’s “unreadability” — influenced by Stein — pointed the way to ever-more-difficult work, until Modernism became Dadaism, and stopped making sense altogether?

Margaret Anderson on Joyce, Stein, and Dada

Margaret C. Anderson was the premier avant-garde publisher of the day in the form of her magazine, the Little Review. Anderson was Joyce’s first publisher in the U.S. and lost an obscenity trial for the privilege. What did she think of Joyce and Stein and Dada?

In her 1930 autobiography My Thirty Years’ War, Anderson relays a comment from Joyce’s wife, on “his necessity to write those books no one can understand” (p. 246). But Anderson goes on to say, “Joyce doesn’t consider it a valid excuse for people to say they can’t read him because he is too hard to understand. When he was a young man he wanted to read Ibsen — wanted it so much that he learned Norwegian in order to read him in the original. He feels that people can make the same effort to read him. He sees no reason why he should make it easier for them” (p. 248).

What did Anderson think of Stein?

Gertrude Stein to-day is noted for….her ‘incomprehensible’ literature….She is convinced that the incomprehensibility of her own prose is a thing of the past. ‘There is of course no one now who has any difficulty in reading me,’ she said, adding that she meant anyone of the younger generation [like Anderson herself]. I for one still have difficulty, a difficulty that is often unrewarded by understanding. And my understanding is often unrewarded by interest….I find the system uninteresting. I don’t deny that it gives weight, but to me it is the weight of boredom….I feel a limitation to the ‘vital singularity’ she is capable of being interested in….I am not at all convinced that her imagination would respond to even a preliminary examination of what I would call significant singularity. [My Thirty Years’ War, pp. 248-249]

And Anderson on the Dadaists?

“May, 1923, was one of those springs when everyone was in Paris….The Dadaists gave performances at the Theatre Michel where the rioting was so successful that Andre Breton broke [Tristan] Tzara’s arm.”

“Nouns Must Go”

Tender Buttons is a short book of prose whose sentences only occasionally make sense. When they do, it feels accidental. There are no characters, plots, events, or situations. There is little punctuation except for periods. Commas are used but sparingly:

When Stephen [Haweis, the painter husband of avant-garde poet Mina Loy] pleaded for the insertion of commas in [Stein’s] long, unpunctuated sentences, Gertrude replied that ‘commas were unnecessary, the sense should be intrinsic and not have to be explained by commas and otherwise commas were only a sign that one should pause and take breath but one should know oneself when one wanted to pause and take breath.’ Following this mimetic demonstration of her principles, Gertrude added that while she had granted Stephen two commas in exchange for a painting, on rereading the manuscript she took them out. The passage concludes: ‘Mina Loy equally interested was able to understand without the commas.’ (Becoming Modern: the Life of Mina Loy by Carolyn Burke, p. 130)

Stein also “struggled with the ridding of myself of nouns. I knew that nouns must go in poetry.” An impossible and ridiculous goal, “nouns must go” has a truly Dadaist flavor. She was a language theorist unafraid to play the iconoclast. Representative excerpts from her essay “Poetry and Grammar” include:

A noun is a name of anything, why after a thing is named write about it. A name is adequate or it is not. If it is adequate then why go on calling it, if it is not then calling it by its name does no good. [….] I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagraming sentences. [….] nouns cannot please, because after all you know well after all that is what Shakespeare meant when he talked about a rose by any other name. [….] I never could bring myself to use a question mark, I always found it positively revolting.

Far from not making sense, Stein made sense sideways. She tweaked the rules of grammar to suit herself and put a bunch of words through its permutations. Since the meaning is so occasional and abstracted, the sound and rhythm take more of the reader’s focus. In 1914, the “dandified journalist” Carl Van Vechten wrote “a piece called ‘How to Read Gertrude Stein,’ explaining in Stein-influenced prose that she ‘has really turned language into music, really made its sound more important than its sense’” (Becoming Modern by Carolyn Burke, p. 150).

Dada evolved “nouns must go” into “words must go,” stated using incomprehensible noises. They swept everything off the table with their nihilisms, their anti-art. The Letterists of the early 1950s did the same thing, and Greil Marcus argued that the Punks of the 1970s did it too. They spit in the eye of making sense.

Most of Tender Buttons reads like the first line: “A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing.” It is plain to see that means nothing in particular. It is difficult reading but the effect can be impressionistic or expressionistic, and intelligible for that. And every few paragraphs, a full sentence arises that refers to nothing, but seemingly makes sense aphoristically, almost accidentally. Here are examples, from the first few pages, of full sentences making half-sense:

Sugar is not a vegetable. [….] What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. [….] A little calm is so ordinary and in any case there is sweetness and some of that. [….] A single image is not splendor. [….] If the party is small a clever song is in order. [….] A lamp is not the only sign of glass. [….] A dark grey, a very dark grey, a quite dark grey is monstrous ordinarily, it is so monstrous because there is no red in it.

That is a rate of one remotely intelligible sentence per page.

Stein and the Dadaists

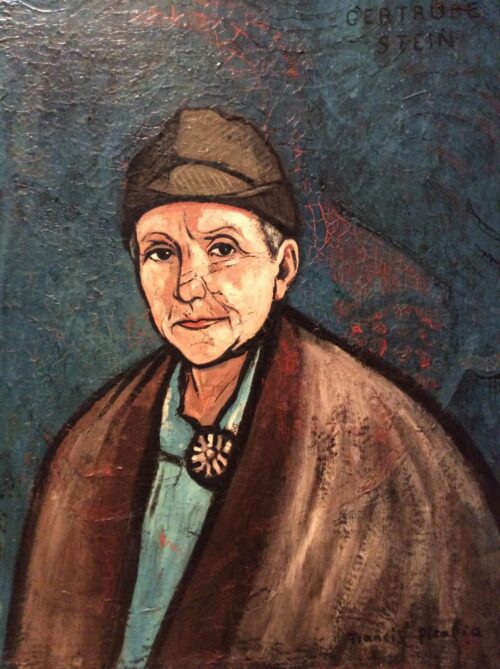

Stein has even been called the “mother of Dada” (a title also sometimes granted to the New York Dadaist, Baroness Elsa; but of course Dada’s true birth mother is the Zurich Dadaist, Emmy Hennings). Stein received a couple of Zurich Dadaists at her salons, Francis Picabia and Tristan Tzara, while mentoring Mina Loy who was associated with New York Dada and Duchamp. Stein befriended Picabia, who painted two portraits of her.

Stein thought Tzara might be good for Loy’s writing, and introduced them. Tzara later offended Loy when he publicly referred to her recently deceased husband, Arthur Cravan, as a President of New York Dada. Loy was appalled; her fresh personal tragedy had been used as a Dada publicity stunt.

Stein later included Tzara in the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which Tzara did not appreciate. Linda Wagner-Martin described it this way: “Tzara called Stein and Toklas ‘two maiden ladies greedy for fame and publicity,’ surely in retaliation for Gertrude’s comparing him to ‘a pleasant and not very exciting cousin’ (“Favored Strangers” p.201).

In “Testimony Against Gertrude Stein,” Tzara continued, “I cannot believe it necessary for me to insist on the presence of a clinical case of megalomania [.…] the measure of the poverty of what we are accustomed to call today ‘intellectual life’.” He’s one to talk. Tzara, who wore a monocle, was an insufferable megalomaniac if there ever was one, “greedy for fame and publicity” indeed.

Tender Buttons, although it barely made sense, still used words. But it helped prepare the ground for Dada’s noise-scapes. Tzara had also borrowed “ideas on vowel structure” from the Futurists. Explicitly writing as a Cubist influenced by Picasso, Stein was trying to see around the words to the subject. There are worse things you could call her than a Surrealist, although she went on to criticize them.

Jewish Lesbian Nazi Sympathizer?

Modernism never fully exorcised Dadaism from its body. Neither did Modernism fully exorcise Nazi sympathizers from its body. Let’s just say some World War II-era Modernists, even the geniuses, were backing the wrong horses. In Stein’s case, at issue is her relationship to the collaborationist Vichy regime of Nazi-occupied France. She was pals with one of the Vichy bigwigs, Bernard Faÿ, who protected her from Nazi persecution for being a Jewish lesbian Modern art collector and all. Stein also praised the collaborationist Vichy President, Philippe Pétain. Both Faÿ and Pétain were later convicted of treason to France. Even if one admires Stein’s writing, her politics were terrible. For instance she opined that America should “control the color line” in its immigration policies. It may also be true that Stein’s detractors overreach, as in the photo included on page 188 in Barbara Will’s 2013 book Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma. This is Stein’s so-called “Nazi salute” at Hitler’s bunker. The photo actually shows Stein and company pointing to something unrelated, and I can only imagine the photo removed from later editions since it does not show what is claimed of it. But given Stein’s politics, the confusion is sadly understandable.

Gertrude Stein vs. Peggy Guggenheim

Compare the WWII stories of two of the most influential avant-garde art collectors: Peggy Guggenheim and Gertrude Stein. There are some similarities and at least one stark difference. To wit, both women contributed incalculably to the early years of Modern art by amassing renowned collections, which supported many crucial artists and movements. Both had amazing, forward-thinking taste. Both were Jewish. Both were narcissists. Both were financially independent. Both led scandalous private lives for their time: Guggenheim was openly promiscuous, and Stein, although monogamous, was openly gay.

Both were in France when the Nazis invaded. Guggenheim had a home in London, but Stein lived in Paris and is still claimed by the French even though she was an American citizen. Guggenheim got as many artworks and artists out of Europe as she could, shipping priceless masterpieces through sub-infested waters before the Nazis could burn them.

Stein meanwhile left her collection in her Paris flat, and moved to the village of Culoz in the French countryside. Her identity and lifestyle were protected from the Secret Police by Bernard Faÿ, one of her best friends, who personally gave a thousand mostly Jewish names to the Gestapo resulting in 600 deaths. But Stein’s name was not one of them. In addition to his silence, Faÿ used misdirection to keep Stein safe (see below). He also may have been able to convince his higher-ups that Stein could be useful to their propaganda machine. In this capacity, she translated Faÿ’s speeches into English, and hoped to get them published in the Atlantic.

How did she rationalize not getting out of France when she had many chances to? Picasso faced the same questions by staying in Paris. He said, essentially, that he didn’t want to move. Stein was similarly glib. In Wars I Have Seen, the totality of her explanation for not fleeing is “I am fussy about what I eat.” The countryside she moved to leaned rightist/pro-Pétain, but as the war dragged on it became more fashionable to aid the French Resistance. Stein did so to some minimal extent, to get the Germans out of what she hoped would continue to be a right-wing France.

Instead, after the war both Pétain and Faÿ were tried and convicted of treason. When Faÿ escaped prison and fled to Switzerland, it is viewed as plausible or even likely that the Stein household financially supported him.

That is how Gertrude Stein survived the Holocaust, and that is the difference between her and Peggy Guggenheim.

Mortal Danger

Which is not to say Stein did not endure mortal danger. Faÿ could keep the Gestapo at bay, but he could not protect Stein from the war on the ground. German soldiers routinely came through the little country village and requisitioned rooms in the Stein-Toklas household. The two American women survived only because they could fake being French, and hid their English-language books. The Germans didn’t even suspect they were Jewish-American lesbians. One slip-up could have been fatal. Another layer of protection was that Stein and Toklas employed servants, and could mostly let them deal with the soldiers. As the war dragged on, some people ratted out their neighbors, and some people in the village were shot on the mere suspicion of aiding the Resistance. Stein and Toklas spent the occupation “obsessively hungry and often afraid [….] hoping theirs would not be one of the French villages burned in the retreat” (“Favored Strangers”: Gertrude Stein and Her Family by Linda Wagner-Martin, p. 255-256).

Stein’s important art collection also barely survived at her Paris flat:

In Culoz, in November [1944], Gertrude and Alice [Toklas] read a friend’s letter telling them the story of the Gestapo’s attempt to take their paintings from the rue Christine apartment. During the last days of the occupation, a group of Germans had entered the flat and, when discovered by a young American neighbor woman who had quickly called the police, were threatening to burn the paintings, which they called ‘Jewish filth.’ Turned away by the authorities because they had improper papers [….] had the Allies not been successful, the Stein-Toklas story might have ended very differently (“Favored Strangers”, p. 257).

All our stories would have ended very differently.

A paper edited by Charles Bernstein, “Gertrude Stein’s War Years: Setting the Record Straight” contains a slightly different, and more detailed, version of how Stein’s collection narrowly survived:

Stein and Toklas returned to Paris in mid-December 1944. It was only after their arrival that they learned from Picasso and others that two Gestapo agents entered their apartment on July 19, 1944 with authorization to search for papers. They showed the concierge photographs and demanded to know how these two Jewish women had remained in their apartment. While the Gestapo searched the apartment, the concierge sent her son down the street to alert Picasso. Picasso immediately telephoned to Faÿ at his office in the Bibliothèque Nationale. The Gestapo returned the next day, and before they left they took a small footstool that Toklas had embroidered after a watercolor by Picasso, some pieces of silver, and some linen. They threatened to return in a few days to confiscate the pictures. As documents seized in Faÿ’s office when he was arrested on August 19, 1944 reveal, he alerted two different German agencies and insisted that they each had authority over Stein’s pictures. By the time the Germans had begun to sort out under whose authority the collection fell, the Paris insurrection had begun and the Germans had more important things to think about.

Regarding Picasso

Regarding Picasso, according to Wagner-Martin, he had “remained safe in Paris, lionized and courted by the Germans [….] and [Stein] had doubts about his companionship with the Nazis” (“Favored Strangers” pp. 255-258). This is poppycock. Wagner-Martin bends over backwards to ignore Stein’s collaborationist sympathies, then dumps on Picasso, who was not “safe in Paris” but regularly harassed by the Gestapo. The frivolous charges that he kept “companionship with the Nazis” is a slur. Whatever else may be true of Picasso, he was a known, lifelong anti-fascist.

If only Stein could say the same. Picasso went on to say of her, to their mutual biographer James Lord: “Gertrude was a real fascist. She always had a weakness for Franco [the Spanish fascist responsible for the “Guernica” atrocities]. Imagine! For Pétain, too. You know she wrote speeches for Pétain. Can you imagine it? An American, a Jewess, what’s more” (Six Exceptional Women: Further Memoirs by James Lord, p. 15).

Best-Case Scenario

Once the war was over, the French government who convicted Pétain and Faÿ of treason probably felt that, since Stein was a famous American who had chosen to be French, she was an overall propaganda win, even if her braying about Pétain was truly obnoxious.

The best-case scenario for Stein’s collaborationist sympathies is the one presented by Bernstein’s paper: that Stein promoted the Nazi-friendly Pétain to save the Nazis the trouble of installing a German government, which would have been worse. Scholars are still fighting about it. But I can’t figure out which makes less sense: her writing, or her politics. I love her writing and I agree, with her, that she was a genius. But like a lot of geniuses, her politics kind of feel like she’s huffing her own farts.

An index of Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here. including more of the Avant-Garde Women series, “from Dada to Situationism”

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments