Duluth’s Granny: Nazi Sub Hunter

August 8, 1945. Duluth, Minn. Heavy with depth charges and a crew of four, the B-25 bomber Beach Baby grumbles off the dusty airfield into the sky on routine sub patrol. The pilot, a Jewish kid from St. Paul, heads into the sun over gleaming Lake Superior. He is the oldest aboard at 22. Light moves around the cabin. The shore drops away and open blue water comes into view all around.

August 8, 1945. Duluth, Minn. Heavy with depth charges and a crew of four, the B-25 bomber Beach Baby grumbles off the dusty airfield into the sky on routine sub patrol. The pilot, a Jewish kid from St. Paul, heads into the sun over gleaming Lake Superior. He is the oldest aboard at 22. Light moves around the cabin. The shore drops away and open blue water comes into view all around.

The tail gunner, a mook from Milwaukee, pipes up on the com: “Everybody knows there ain’t no Nazi subs in the Great Lakes. Hitler’s been dead three months.”

“Tell that to Granny down there,” the pilot says, “War’s not over.”

They spy the fishing boat to starboard and the zig-zag black-and-white lines of its weird paint job. The navigator speaks with his Michigan accent:

“She’s doing up here what Hemingway’s doing in the Caribbean: hunting for U-boats at the bottom of a whiskey glass.”

The side gunner laughs like the North Dakota yahoo that he is. “Well what do you expect, she’s from Duluth.” Now they’re all laughing.

They quit laughing as engine #1 flames out. Holes appear in the fuselage, the engine breaking up throwing shrapnel of itself. The pilot says, “Ope — stabilizer’s gone. Brace for impact.” He skips the plane along the calm water like he’s skipping a stone. Then it sinks like one.

Three days later. No land in sight, the sun sets on the somber bomber crew, alive but sunburned and uncomfortable in an inflatable life raft. They paddle up to a large yellow rescue buoy.

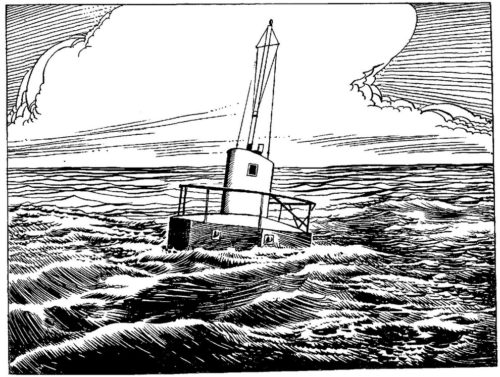

It is a rectangular platform of welded steel, 25 feet by 15 feet, two feet higher than the water line. Ringed with a railing, it is accessed by ladders sticking in the water. An eight-foot tall conning tower in the center stands painted with the Red Cross. A yellow flag flies from a flagpole clustered with an antenna and a roundtop stovepipe.

Lake Superior rescue buoy, 1945

“There’s a fleet of these out here since Pearl Harbor,” says the pilot.

“It looks like a little submarine tower,” the tail gunner says.

The pilot reaches for a ladder: “It’s the opposite of a submarine — it’s for rescue.”

They haul themselves aboard, peer in the tower’s little portholes. A ladder descends into a dark volume.

“This thing has a floor or two below the waterline,” the pilot says, “It’s a floating hotel.”

The hatch displays a plaque: “Welcome to Rescue Buoy #7. You are 12 miles from shore anchored in a depth of 1000 feet. Make yourself at home. May your wait be a short one. Inside are all the comforts.”

“That’s quite welcoming, isn’t it?” the side gunner remarks.

The pilot, flatly: “Uncle Sam bought ’em from Canada.” They open the hatch and, finding a light switch, climb down the ladder one by one.

They stand inside a rectangular living room with a kitchenette at one end, gentle slapping of the waves audible above their heads. Cupboards of food and first-aid ring the wall of the kitchenette side. Shelves of books, games, and amusements line the living room side, around a square inset table with seating for four. Off of the kitchenette, a wall-mounted two-way radio hangs over a folding stool and a drop-down writing surface, tethered pen and compass by a pouch of maps and graph paper.

“Hey this place is alright,” says the navigator.

“You like those maps,” teases the tail gunner.

The pilot stands at a ladder going into the floor. “Bunks are down here.”

Four bunks against the walls by racks of towels, fresh clothes, and toiletries. Fishing poles and an acoustic guitar lean in a corner.

“Where’s the bathroom?” asks the side gunner.

“The lake’s a giant toilet,” says the navigator, slapping him on the back of the head, “Where do you think the birds go?”

The pilot kneels by a hatch he’s opened in the floor. He pulls out a bottle of cognac. “Wine cellar’s this way, lads.”

Tail gunner from upstairs: “I found the cigarettes!”

A few days later. The woman known as Duluth’s Granny pilots her dead husband’s wood-hulled steam-powered fish tug, the Sea Hag, up and down the shore like she’s done these decades without him. The angular crosswise zebra striping confuses the boat’s true contours. But it’s her boat now and everybody knows it.

The papers quote her: “Nazis past the locks peering through periscopes think they see a battleship at a distance, when it’s Granny’s tug on top of them. Hunted German subs here in the first World War. Ain’t stopping now.”

Accompanying photos show this gruff old eccentric seadog with her black rain gear and the corncob pipe she chews like a piece of fish jerky. Her weathered face like an old elephant seal frames itself with the wiry white hair escaping the brim of her sou’wester.

Wearing a cork life jacket over her oilskin raincoat, she turns the pilot’s wheel toward a silhouette that could be the conning tower of a U-boat. She hears a whiskey bottle rolling across her deck. Or maybe it’s a loose grenade. She’ll find it.

Steaming closer now, the silhouette resolves into one of the brightly colored rescue buoys. She’s got a chart of them somewhere. The Sea Hag rolls up to it. She sees the inflatable life raft bobbing tethered to the railing.

Amid the fishiness of her own boat lousy with salmon scales and damp nets, she detects a whiff of flapjacks and cigarette smoke escaping the thin chimney on the conning tower. But the signal flag is still solid yellow, indicating the buoy remains vacant.

“It’s full of instructions, can’t they read? Maybe they’ve got head wounds. I’ll check it out and radio the Coast Guard, as if they’ll listen to me.”

Alongside now, she leans over her deck rail and bangs on the buoy’s hull with a gaff hook.

“Hello in there! Anybody home? Hello!”

Presently the pilot emerges, peeking through a porthole in the tower. Then he sheepishly opens and steps through the hatch. Granny hears Billie Holiday playing on a gramophone down inside while billows of cigarette smoke escape into the open air.

The pilot says, “Is that Duluth’s Granny with her famous dazzle camouflage? Hey guys, come up, it’s Granny to rescue us.”

Indistinct voices from below. The pilot faces her. “You see Granny if it’s not too much trouble, we’re playing a sweet cribbage tournament and it’s my turn. So, perhaps you could come back, say, Tuesday?”

“Why aren’t you flying the striped flag? You’re supposed to raise it so people see you’re here.”

“Striped flag? I don’t know anything about a striped … hey fellas, do you know anything about a …”

“Haven’t you radioed for help? Is the radio broken?”

“Battery’s dead, but we left a note in the comment box about it.”

“Come on with me then, I’m rescuing you right now. We’ll be in Duluth by nightfall.”

“No really, we’re good, I mean thanks but …”

“You’re the B-25 crew shot down by that Nazi sub a few days ago, aren’t you?”

“What! Goodness, we had engine failure. Why do you think …?”

“I was there. I would’ve picked you up but I had to give chase. Glad you understand.”

Plaintive voices from inside. The music changes to bebop.

The pilot says, “Well I don’t know who’s drunker Granny, me or you. Look. Can you just report us rescued? I mean, we are, you’ve just … when you come back, I mean …”

Granny chews her pipe, grumbling, “Don’t know when I’m coming back.” She turns to her wheel, calling over her shoulder, “I’ll check on you.”

The pilot shouts, “Bring puzzles?”

Granny came back three weeks later.

Sub hunting had been slow and quiet as usual. Some rough weather but nothing too terrible. Full sun lately, a fine end of summer. The sea was moody but the rescue buoy only swayed back and forth like a loving mother. The crew had installed a clothesline, and the tail gunner worked on his tan while fishing from a lazy hammock. She tossed him a mooring line.

“I have groceries,” she said.

He called the fellas and she refused their thanks as they transferred the goods: cases of wine, sacks of flour and rice, beans, cheese, eggs, powdered milk, sugar, salt, dried fish, dried fruit, canned ham, cartons of cigarettes, matches, candy, toilet paper, coffee, ice, socks, underwear, some sweaters, some puzzles, and lastly, a newspaper.

Her hand reached from the indistinct borders of her crazed boat like she was handing the pilot news from another dimension. He unrolled the paper and read the headline. The other crew looked wide-eyed over his shoulders.

Granny said, “War’s over, boys. For you anyway.”

She puttered off as they read the paper in the sun.

An index of Jim Richardson’s essays here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments