N is for Nostalgia: Peak Bradbury

When my father died, I had a surrogate dad waiting in the wings: the work of Ray Bradbury. I was obsessed. I felt I would devote my life to him, a feeling common to loves which last no more than a couple years, as this one did. But they were timeless years. Between my 13th and 15th birthday, with my adult future on the horizon, I was still young enough for summers to last forever.

When my father died, I had a surrogate dad waiting in the wings: the work of Ray Bradbury. I was obsessed. I felt I would devote my life to him, a feeling common to loves which last no more than a couple years, as this one did. But they were timeless years. Between my 13th and 15th birthday, with my adult future on the horizon, I was still young enough for summers to last forever.

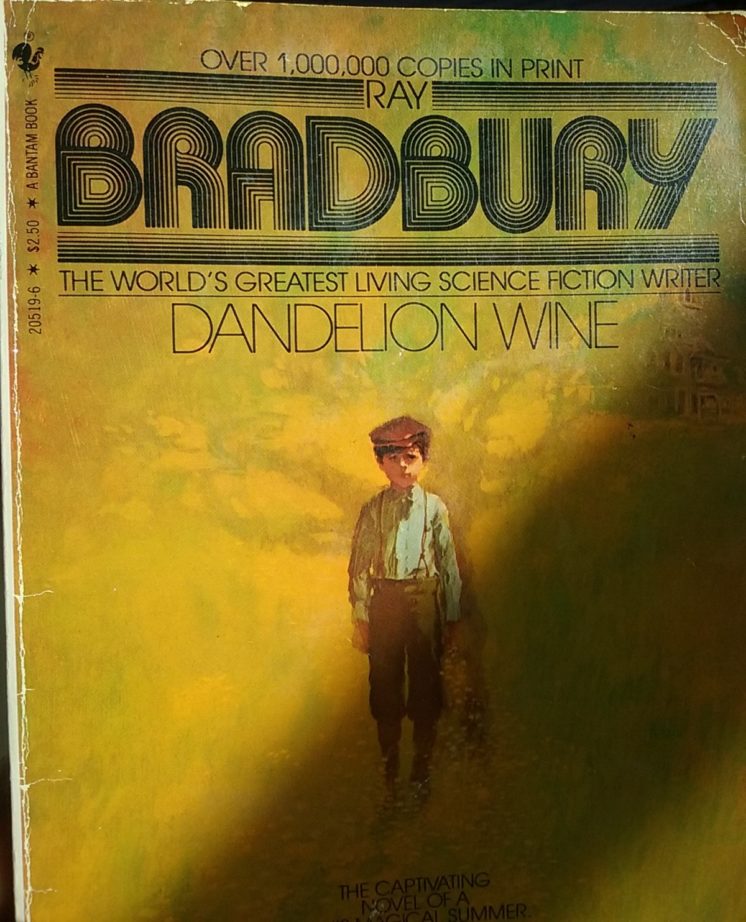

Now in my 50s, I retain the suite of Bradbury paperbacks I collected back then. I have no use for them, although no library contains merely useful books. I quit re-reading them decades ago. But there are many reasons for books to be collected. I moved on to obsessions with writers less old-fashioned and less overly lyrical, although not before his lyricism infected my own style. Yet even for me, Bradbury is too breathless and too wordy (although not chatty like Harlan Ellison). He wrote terrible poetry. He became a cranky old man. Film and TV adaptations of his work are, by and large, bad. I now consider him (along with his contemporaries Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein) to be a branch of Young Adult (i.e., children’s) literature. But I still give his books a treasured pride of place on my shelves, which overflow with his successors. Strangely, most of my adult favorites also begin with the letter “B”: Burroughs, Ballard, Borges, Bowles … but Bradbury got to me first.

When I was 14 — peak Bradbury — Dad died of a heart attack. That may be one reason why I have failed to return to the once-treasured pages: the weight of nostalgia burdens them. But back then, with Dad suddenly gone, Bradbury remained, becoming the first of many substitute fathers. Now he too dwells in the past like my real father does. As Bradbury described death in his time-travel story The Toynbee Convector, “He was travelling in the past now, forever.”

Shortly before Dad dropped dead, I was gifted a Bradbury book by my friend Andy Prior for my 14th birthday. Andy knew of my obsession. The book was Dandelion Wine. Like the Martian Chronicles, it is called a novel but it’s really a collection of short stories in a common milieu. And like Something Wicked This Way Comes, it is Bradbury’s semi-autobiographical meditation on the twilight of childhood, which I was living without knowing it.

Set in the summer of 1928, Dandelion Wine’s main character is 12-year-old Douglas Spaulding. I opened the book for the first time while sitting in a tree in Maryland in that April of 1983. Douglas had an annoying little brother like I had, and a larger-than-life father like I had. I came to the following lines in the first chapter, where Douglas and his brother are roughhousing in the forest as their father looks on, a scene I had lived my whole life. Bradbury describes Douglas becoming conscious in that moment. As I read the words, my own self-awareness blossomed, and I felt the same sensations Bradbury felt in 1928. The book conjured me to life with these words:

In silence they lay, hearts churning, nostrils hissing. And at last, slowly, afraid he would find nothing, Douglas opened one eye.

And everything, absolutely everything, was there.

The world, like a great iris of an even more gigantic eye, which had also just opened and stretched out to encompass everything, stared back at him. …

I’m alive, he thought. …

The grass whispered under his body. He put his arm down, feeling the sheath of fuzz on it, and, far away, below, his toes creaking in his shoes. The wind sighed over his shelled ears. The world slipped bright over the glassy round of his eyeballs like images sparked in a crystal sphere. … Ten thousand individual hairs grew a millionth of an inch on his head. He heard the twin hearts beating in each ear, the third heart beating in his throat, the two hearts throbbing his wrists, the real heart pounding in his chest. The million pores of his body opened.

I’m really alive! he thought. I never knew it before, or if I did I don’t remember! … Think of it, think of it! Twelve years old and only now! …

Dad knows, he thought. … He’s in on it, he knows it all. And now he knows that I know. …

I mustn’t forget, I’m alive, I know I’m alive, I mustn’t forget it tonight or tomorrow or the day after that.

It was my first satori. The experience electrified me, a literary magic trick to rejoice the dreams of Dr. Frankenstein: “He’s alive!”

Two months later, I was to visit my older friend/big brother figure Jason Bauer, in New York City for a week. Saying goodbye on the train platform, Dad informed me I was an adult now, and ceremoniously shook my hand. He did indeed know that I knew.

In New York, Jason (an actor who loved giving theatrical readings) read me Bradbury’s story about irrevocability and death, A Sound of Thunder.

Dad died while I was away. Bradbury had only just inducted me into life. Dad had only just inducted me into adulthood. Now I had to grow up in a hurry, and I did so with my head in books.

Mom moved us to Texas and I went off to ninth grade. In between classes, I quizzed my English teacher Mr. Heberling about Bradbury. Heberling appreciated my love of reading and my enthusiasm, but he did not share my feeling that Bradbury was the greatest writer in the universe. He listened, and then tried to let me down easy. He explained, “Bradbury uses too many exclamation marks — if a sentence works, it doesn’t need one … He’s good at what he does, but he’s sort of a one-trick pony.” True! But what a trick it was!

The summer between 9th and 10th grade, I found a used bookstore in Houston within walking distance. It had a wide selection of vintage science-fiction paperbacks and I scooped up all the Bradbury books I didn’t already possess. In his short story collections, with fantastic titles like R is for Rocket and S is for Space, I learned to stop myself from accidentally spoiling the endings. While reading down the second-to-last pages, if I wasn’t careful, my eyes could see the last line waiting in the future. From necessity, I developed the lifelong habit of putting my hand over the end, until its time came. The practice serves me well to this day.

Once I’d read all the Bradbury books in the bookstore, my hunt continued at a finer level of granularity. I discovered those wondrous objects called short-story anthologies. Things with titles like “Best Sci-Fi Stories of 1951” and “Nebula Award Winners of 1964.” The shelves were full of them stretching back into unimagined epochs, collected by year, by awards won, and by pulp magazine titles. In these pages, lesser-known Bradbury stories hid among those of other authors. I opened endless anthologies one-by-one as summer progressed, to the tables of contents, and scanned methodically for these unknown gems. When I found one, I read it right there, sitting on the tile floor. The staff never kicked me out.

I spent those afternoons among the smell of old paperbacks, like a Biblical scholar poring through Dead Sea scrolls for lost fragments. I can recreate the memories at will by cracking open an old Bradbury and inhaling. Like smelling the aged newsprint of comic books, I no longer have to read them, a single whiff transports me. Scent is the closest thing to time travel. I “vanish from the present” (Toynbee again). I “run back down the years home” to the era when Ray Bradbury first informed me, to my astonishment, that I was alive.

An index of Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

2 Comments

mlatsch

about 3 years agoJim Richardson (aka Lake Superior Aquaman)

about 3 years ago