Duluth, Minnesota and the Lost Confederate Gold

In 1861, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey was in Washington D.C. when the Confederates started the Civil War. He was in the Oval Office when Lincoln received the fateful telegram detailing the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina — the most serious in a string of Southern aggressions, including the seizing of Federal armories across Dixie. Heeding Lincoln’s call for troops, Ramsey walked right up to the President and said, “Mr. President, let Minnesota be the first state to commit 1,000 volunteers to answer this latest outrage from the disloyal states.”

In 1861, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey was in Washington D.C. when the Confederates started the Civil War. He was in the Oval Office when Lincoln received the fateful telegram detailing the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina — the most serious in a string of Southern aggressions, including the seizing of Federal armories across Dixie. Heeding Lincoln’s call for troops, Ramsey walked right up to the President and said, “Mr. President, let Minnesota be the first state to commit 1,000 volunteers to answer this latest outrage from the disloyal states.”

Ramsey’s commitment created the famous fighting force known as the Minnesota First Infantry Regiment. They were the Civil War’s earliest northern enlistees, and they saved the Union at Gettysburg as every Minnesota schoolchild knows. On the third day of that pivotal battle, after Pickett’s Charge, Pvt. Marshall Sherman of St. Paul emerged with the scarred battle flag of the 28th Virginia Infantry. Virginia whines about it to this day but we’re not giving it back neener neener neener.

A Duluthian, Buckminster Wilde — hunter, trapper, moonshiner, bachelor, and disowned cousin of the financier Jay Cooke — was among those who had heeded the Governor’s call to form the Minnesota First. Duluth at that time had few large buildings — mostly sawmills. The city was mainly a collection of shacks and tents. To enlist in the war, Wilde made his way on horseback down the old army road to Minneapolis, the milling capital of the world. Those who enlisted here formed the First’s Company D, the so-called “Lincoln Guards.”

After his sharpshooting skills were recognized, he transferred to the First’s Company L, also known as the Second Minnesota’s Sharpshooters Company, under Captain William Russell. As a sharpshooter he could place ten consecutive shots in a ten-inch circle at 200 yards without a scope. His uniform was dark green, and the infantrymen teased him, calling him “Robin Hood.” He was issued the best rifle of the day, the Sharps Model 1859, with its triple-fast loading time and supersonic hollow mercury rounds that hit you before you heard the shot.

Wilde formed a bond within Company L with three other Duluthians, a company within the company calling themselves the “Hillside Irregulars.” As they marched far from home, they reminisced about the way blazing light pooled on Lake Superior in the mornings.

The Minnesota First are remembered for being particularly tall, strong, and hardy men who knew their way around axes and guns. It was noted they could build bridges better and faster than any other regiment in the army. And Company L received more extensive training than most infantry. In addition to sharpshooting, they were expert skirmishers — the finest soldiers in the country.

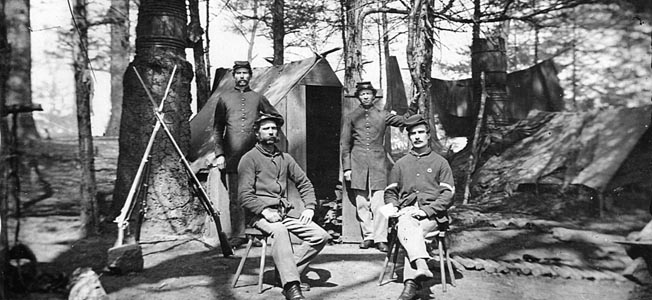

The Hillside Irregulars. Clockwise from lower left: Buckminster Wilde, “Fancypants” Nettleton, Henri “Enragé” Cloquet, “Old Babyface” Bong

The Battle of Gettysburg

During the Battle of Gettysburg, Wilde witnessed many sights that made him wonder if Hell had come to the surface of the Earth. He witnessed Lt. Col. Douglas Fowler shouting amid cannon fire, “Dodge the big ones, boys!” and the very next second Fowler was decapitated by an unexploded shell spattering his brains across his men.

Wilde then witnessed Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson amputating his own leg with a pocketknife while continuing to bark orders.

Then Wilde survived the largest artillery barrage in the Western hemisphere, albeit because the Confederates’ mis-aimed cannons shot clear over the Union’s heads. The empty field behind the Union lines took an awful beating however, leading to Wilde’s famous quote, “Maybe those boys should have stayed at West Point instead of thinking they know how to win a war.”

Wilde was one of the 250 men tasked with charging 1,500 of Stonewall Jackson’s men, which in effect saved the Union at a cost of an astonishing 85 percent casualty rate including the middle finger on Wilde’s left hand. Faint with blood loss during the three hours of intense fighting, Wilde collapsed amid the scorching summer temperatures, and thus missed the moment when his compatriot Marshall Sherman captured the Confederate battle flag.

As documented on the website Blurred Bylines, an unnamed soldier from the First wrote these lines about the charge:

If men ever become devils that was one of the times. We were crazy with the excitement of the fight. We just rushed in like wild beasts. Men swore and cursed and struggled and fought, grappled in hand-to-hand fight, threw stones, clubbed their muskets, kicked, yelled, and hurrahed.

I’ve lost the reference but history also notes, “Only smoke and twilight saved the regiment from complete destruction.” Historian Tucker Glenn wrote, “No soldiers on any field, in this or any other country, ever displayed grander heroism.” And according to William Watts Folwell, “There is no more gallant a deed recorded in history.”

Two days later, among dead soldiers, horse carcasses, and swarms of large green flies, war photographer Alexander Gardner and his men rearranged a pile of bloated corpses to make a better picture. Wilde revived and, clawing his way free of the putrefying stack of bodies, he nearly frightened Gardner half to death.

Wilde was sent to recover in hospital at Camp Letterman. According to army records, this is where he died from his infected wound. The Minnesota historian Peter S. Svenson turned up an entry in the journals of Walt Whitman, who was a Camp Letterman nurse:

Vex’d at the sudden death of B. Wilde. Just yesterday he had been rosy-cheek’d as we vig’rously and warmly discuss’d natural philosophy. Alas today his bed lies empty and I have receiv’d the dreadful news. Infection they say — how quick Death rides us down. Would that I might hold him to my bosom e’en once more.

The Secret Service

At least, that was the story until 1989, when Svenson discovered a few lines in the 1865 diary of U.S. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase. According to Svenson:

Chase worked closely with Jay Cooke the financier to fund the Union war effort. In the process of forming the national banking system, Cooke secured loans from Northern banks and sold bonds that funded the Union army. But money was tight. Secretary Chase and Cooke set their sights on an alternate source of funding: the Confederate Treasury. It was the rightful property of the United States, after all. And thus began a secret chapter of the war, a spy mission to repay the war-loans of the Northern banks, recouping the war’s costs from the Confederates by stealing their money.

Nothing else was known of the plan until anomalies turned up on Wilde’s death certificate during the course of filming Ken Burn’s 1990 Civil War documentary. It didn’t make the final cut of the series because it opened up a can of worms that warranted its own as-yet-unmade movie. But a forensic analysis showed the certificate to be a clever forgery. Why should a random soldier — a patriot — have a fake death certificate? And the answer appeared to be: because Wilde had been deputized as a prototypical Secret Service Agent, an agency so new it had not been officially created yet, like the OSS was the forerunner of the CIA. Wilde was going deep undercover behind enemy lines. His backstory had to be flawless. Receiving fake documents supplied by Union superspy Allan Pinkerton, he assumed a fake identity as a Confederate soldier — Wilde was now a Maryland secessionist volunteer named John Buzzcock. Flawlessly imitating a Baltimore accent, he infiltrated the Confederate Treasury guard with the help of the Union spy network, and pulled off the greatest heist in the annals of crime.

When General Lee surrendered, Confederate President Jefferson Davis escaped the rebel White House in Petersburg on two trains — one full of his cabinet and their families, and one hauling the combined funds of the Confederate Treasury: millions of dollars in gold nuggets, gold coins, silver bars, Mexican silver coins, and Confederate paper money currently under pressure of 9,000 percent inflation and food riots. Their guard was two hundred Confederate troops, some as young as 12 or as old as 86, and they were all hungry. Among their number: John Buzzcock, 30. The fox had been put in charge of the henhouse. Wilde had been analyzing the best way to relieve the rebels of their filthy lucre for two years since going underground. One thing he found was that your average Confederate soldier disliked physical labor and considered it “slave work.” No stranger to physical labor, Wilde quickly advanced in the ranks, aided by strategic sniper attacks against the Confederate officers ahead of him in the chain of command.

The Greatest Heist in the Annals of Crime

By this time the other Hillside Irregulars had been captured at the Battle of Mine Run, escaped, and were conducting guerrilla warfare against the South. They played the role of Wilde’s guardian snipers, making contact with him and shadowing Jefferson Davis’ very slow getaway trains pulled by degenerate Confederate engines.

At a junction one midnight, they distracted the weary guards with a pile of sandwiches and some of Wilde’s “special recipe” moonshine the Irregulars distilled at their camp in the boonies. They relieved the Treasury car of its filthy lucre, loading the spoils onto a getaway train supplied by Pinkerton. This is the now-famous spy train christened as the John Henry Pepper, a train in disguise: it looked like one of the broken-down and busted Confederate engines, when really it was a federal stalwart capable of the then-unheard-of speed of 60 miles per hour. When the Confederates opened the decoy crates and barrels of their money train, which they expected to be full of precious metals, all they found were rebel bodies, rocks, and garbage. By the time Jefferson Davis realized the money had been stolen, Wilde and the Hillside Irregulars were halfway to Washington D.C., waved through at every Union post by agents of the U.S. Treasury.

Davis, already drunk on apple brandy in the late morning, nearly had a stroke. Here he had been trying with all his might to conjure mighty armies from his imagination. Now hundreds of millions of dollars had disappeared overnight as unpaid rebel soldiers and starving southern citizens rioted. By the time Davis was captured — whether or not in his wife’s petticoats is irrelevant — the boxcar of Wilde’s loot was being put under guard in the National Bank.

Wilde (now Agent Buzzcock) and the Irregulars were honorably discharged, and took a train to Chicago. There they chartered the schooner Phoenix, and sailed through the Soo Locks to Lake Superior and Duluth.

It was around then that Treasury Secretary Chase and Jay Cooke became aware of a problem at the National Bank. The crates and barrels of gold and silver were in fact full of rocks and garbage, topped with a little bit of money to look stuffed full of riches. But all told the total amount, out of an expected $200 million, was closer to $35,000.

A mysterious 1873 letter to Cooke, found in the Cooke archives by the historian Svenson, reads:

Dear Cousin,

In appreciation for all you have done for me, I fought for years in intolerable conditions behind enemy lines and retrieved what you asked for — in exchange for a generous cut of the profits of course for which I am very much thankful. But as for who was delivered the lion’s share of this fount of wealth, was it not right that the people should have it, instead of the powerful? For who has lost more, businessmen like yourself pushing papers behind a desk, or the civilians who kept the home fires burning, or men like the Irregulars who watched over me like angels in the heavenly sights of their rifles? Those men — Old Babyface Bong, Fancy-Pants Nettleton, and Henri Enragé Cloquet — vowed with me to build this ramshackle city into a fantasy metropolis on the waters. If you want your money, come and get it — you will find it in the railroad, housing stock, city streets, and all the great landmarks of this town which we have built with our own hands — like our new canal which flows as freely as the tears of Jefferson Davis. We have made a down payment on a grand bridge to span it. You can even take the credit if you wish but the money’s all spent. Those who wish to recover the lost Confederate gold can come melt down our city. Try it. Just as the state of Virginia whines like a spoiled child to get its battle flag, together with all right-thinking Minnesotans I invite them to kiss my ass. I salute them with the phantom pain of the middle finger I lost during that charge.

There are still a few stacks of Confederate paper dollars left but most of it we have gleefully used to light our cigars, and the woodstoves of our social clubs in the wintertime. They burn brightly casting a joyful light upon our faces. We have created this city on a hill on the death of the slave-owners and those poor whites who aspired to be slave-owners. Many at our own hands as we slit throats in back alleys behind Georgia taverns and the twilight riverside ports of the Carolinas. Let Minnesota always remember our great victory over those who would enslave their fellow children of God. If the crackers hate the Black Man, their ancestors should not have shipped them here in chains by the boatload. What they hate is a Free Black Man.

And I want no part of your Indian Wars you bastard; have not the previous ones been bad enough? I hear your new railroad is doing so poorly it has cost you the job of Secretary of the U.S. Treasury and collapsed the economy of the Western world. Shame. Remember cousin, I know where all the bodies are buried, and so I know you will continue to keep your silence. One letter from me to the New York Times and your goose is cooked, even more thoroughly than it already is. You suck harder than ticks on a mule.

On my honor, John Buzzcock.

An index of Jim Richardson’s essays can be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments