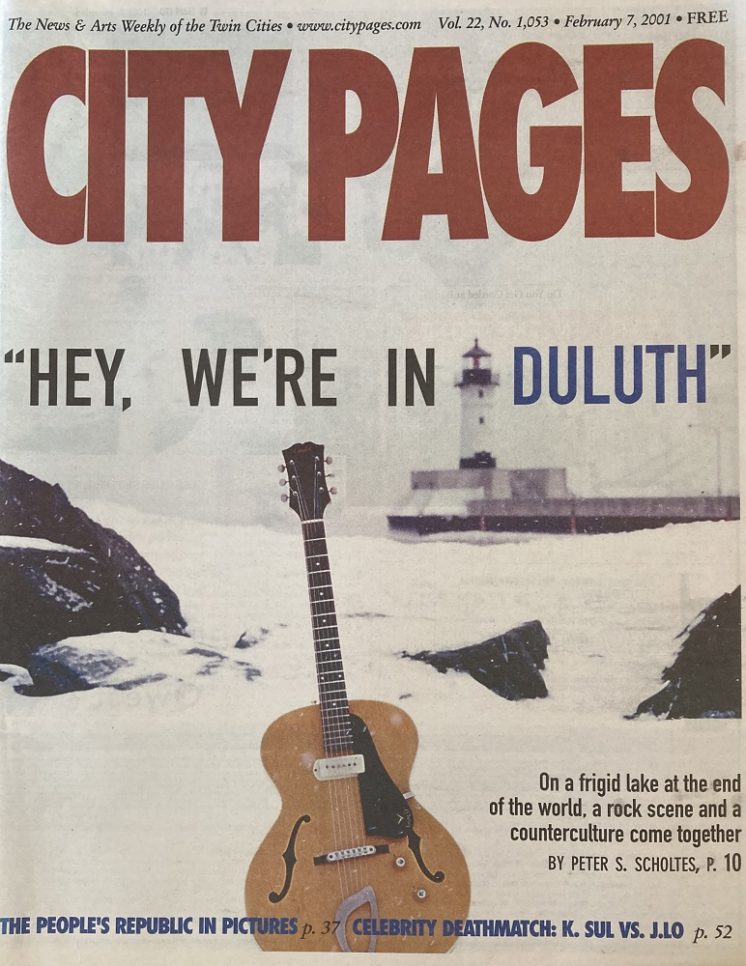

City Pages: “Hey, We’re in Duluth!”

Twenty years ago today — Feb. 6, 2001 — City Pages published a cover story on Duluth’s “tiny counterculture.” The Twin Cities alternative weekly paper ceased operations last fall and its online archive is on hiatus, but Perfect Duluth Day is here with the flashback goods.

The Minnesota Historical Society, Hennepin County Library and Newspapers.com will be hosting online archives of City Pages in the future, according to a notice on the homepage of citypages.com.

“Hey, We’re in Duluth!”

On a frigid lake at the end of the world, a rock scene and a counterculture come together.

by Peter S. Scholtes

photos by Teddy Maki

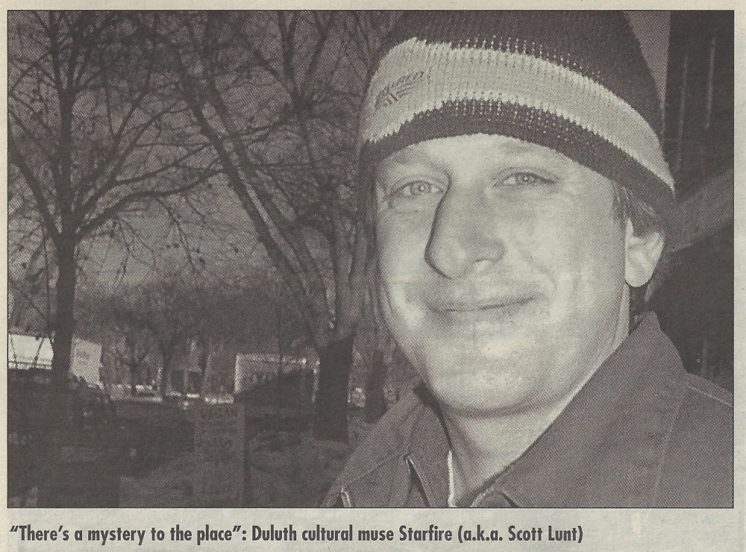

Starfire’s jacket is not warm enough. The wind off the lake seems to be bypassing his measly layers of T-shirt and skin to pierce right through to his vital organs. Yet Starfire, who is well accustomed to a malicious climate, lifts his hands up as if to rub the air between his thumb and forefingers and discover just what substance is blasting through his cotton delivery jacket. “There’s a definite vibe to Duluth right now,” he says, gesturing toward the space between us. “There’s a mystery to the place. And I don’t know what the secret is or how to explain it. I almost don’t want to figure it out, because as soon as I do, it might disappear. I don’t want to ruin it by thinking about it too much.”

Leave that to me, I say. And we laugh, cutting across the cobblestone toward an almost empty parking lot that curves steeply uphill, like the rest of downtown Duluth, toward the gray mists of the waterfront sky. I’m convinced that the “vibe” Starfire can’t put his finger on — call it the emerging sense among Duluthians of an emerging sensibility among Duluthians — might be gauged by the water levels in his eyes. These pools are known to overflow before the live majesty of Duluth’s best-known band, Low. Today they shine like a bluish version of Bill Bixby’s “Don’t make me angry” irises in The Incredible Hulk. You can believe, from their intensity, that this onetime ambulance driver would power his own pirate radio station, as he did on the sleepy hillside between 1997 and 1998, before the FCC mailed out the usual threats against person and property.

If Duluth is like a New Orleans cemetery, beautiful but dead, no one has told Starfire, who seems to hope for spring weather in January. Right now he’s too busy making local culture to explain its causes, so I give him a lift, driving past the one-of-a-kind R.O. Carlson’s Used Book & Record — my ideal store: a garbage house with price tags — toward a large warehouse filled with art studios. Inside, we come upon a dark rehearsal/recording space adorned with oil paintings and white Christmas lights, a room that Starfire says his country band — of course this sentimentalist fronts a country band — shares with a few other groups for a total of $100 a month. He introduces me to sound engineer Eric Swanson, a grizzled industry vet with a white ponytail and plenty of mellow production advice for Starfire, who is polishing off vocals for what will be the debut album from Father Hennepin.

“I always feel like ‘We Are the World’ when I sing like this,” Starfire says, clamping a pair of headphones around his dirty-blond bed-head and sidling up to the standing mic.

“A friend of mine worked that session,” remarks Swanson, remembering an anecdote about Stevie Wonder showing Ray Charles the way to the urinal — the blind leading the blind. The tale has the scent of urban legend, though it’s also the kind of yarn you want very much to be true.

Anyway, Starfire is ready to go. “What would Jesus do,” he begins in a Martin Zellar-pitched quaver, “if he spent a day in my shoes?” I look at Starfire’s shoes: suede tennies. How perfectly thirtysomething punk, I think. Like his “Technicolor DJ” title in place of the blunter birth name Scott Lunt. Or the modest cultural transformation he has tried — and tried and tried — in this perennially depressed industrial port.

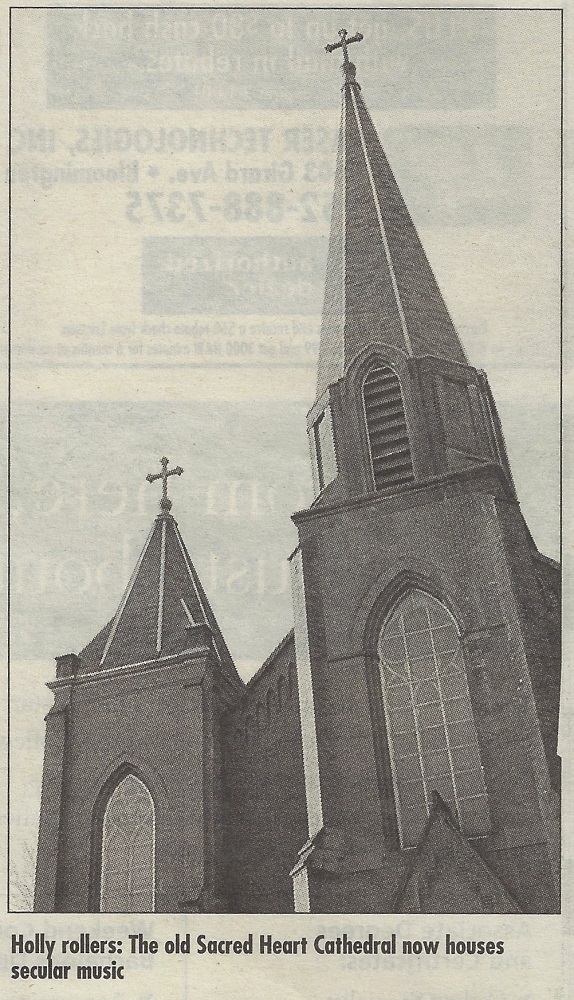

Watching Starfire sing, I’m put to mind of an incongruous but memorable image that I return to whenever I think about Duluth’s revitalized alternative culture, which lately is a lot: the sight of a lawn mower jutting out from beneath the curtain of a church confessional. I noticed this very thing upon my first visit to the century-old Sacred Heart Cathedral, a historic landmark that was saved from the wrecking ball by preservationists who turned the place into a secular music center. Just think how much good humor was required to relocate the garden tools to the booth of contrition. The mower struck me as a characteristically “Duluth” balance of defiance, self-deprecation, and practical good sense. (In the end, somebody probably just needed to find a place for the damn thing.)

This is also the composite attitude you find among counterculture types beneath the layers of army rags and wool. You can even hear a certain practical defiance in Starfire’s song about what Jesus himself would do after a day of being Scott Lunt. Answer: “He’d probably just say, ‘Shame on you.”

Swanson says that he once wondered how Low guitarist Alan Sparhawk, a former member of Father Hennepin and a current Bible teacher, felt about “What Would Jesus Do?,” the first song Starfire wrote for the band. But there’s nothing offensive there, he adds. “Oh, and that $5,000 microphone Starfire is recording on was loaned by Al, too,” Swanson says — one of the many benefits of having a nationally known indie-rock trio in your cozy midst. In a few short days Starfire will hit the road with Low to assume yet another hat — as nanny to the ten-month-old daughter of Sparhawk and drummer Mimi Parker — and he wants to finish the album before he leaves.

So Starfire moves on to the next song, “I Like it in Duluth,” trying on the melody in various voices. Between takes, friends and lovers start quietly trickling in. Eric Swanson’s fiancée shows up with soup; Father Hennepin’s guitarist arrives with beer. Chris Monroe, a cartoonist for Duluth’s alternative weekly the Ripsaw News, and the Star Tribune, walks in and smiles when she hears the lyrics of the song, a “California Girls”-style tribute to the Twin Ports written, I’m told, by a local jug band from the Seventies with a name that screams ‘local jug band from the Seventies”: the Moose Wallow Ramblers. “Where else in the nation can you get cheaper refrigeration?” goes one line.

Those lyrics notwithstanding, this room is warm, and it grows warmer and more relaxed with the company. Finally Starfire sets down the headphones to take a break. Everyone talks about recent events in town — like the decision of Lake Superior College not to fund a downtown charter school. And everyone seems engaged by issues with a neighborly immediacy. The folks in the room all seem locally active in a social way — in art, music, and politics — and everyone seems somehow connected to the Ripsaw News, a weekly newspaper that combines all the dark, close-knit community humor of a doomed Russian submarine with up-to-date broadcasts and broadsides written for activists who, on second thought, might yet storm the palace.

“The political climate here is really in turmoil,” Starfire tells me. “I love it. Because there’s an old-boy network of developers who are used to just sort of pushing things through — like the Tech Center.” He’s referring to the Technology Village/Soft Center project, a block-long downtown office complex that spurred the muckraking Ripsaw into existence two years ago and where the charter school was slated to take up tenancy. Volume 1, issue 1 of January 1999 broke the story that the city had begun demolishing historic buildings before a wrecking permit had been won (or even legally bid), in order to dodge a legal appeal. The paper went weekly last April and has since become the hub of the local counterculture, drawing dozens of volunteers, while the hopeful Soft Center stands largely vacant. Starfire, who shares an unpaid paper route with Chris Monroe, says the newspaper has, in many ways, picked up where his 100-watt station, Random Radio, signed off. The Ripsaw is its own sort of village and center.

The very notion of alternative culture has become so co-opted and commercial and debased as to have lost all meaning; it’s a marketing term now. But living in a city where nearly the only live music is rawking cover bands, and the only movies on offer are those at a solitary six-plex — which is to say, Duluth about three years ago — will erase one’s cynicism, and fast. The existence of an organic alternative to prefab national entertainment product takes on a special urgency in a town where paint huffing is said to be on the rise.

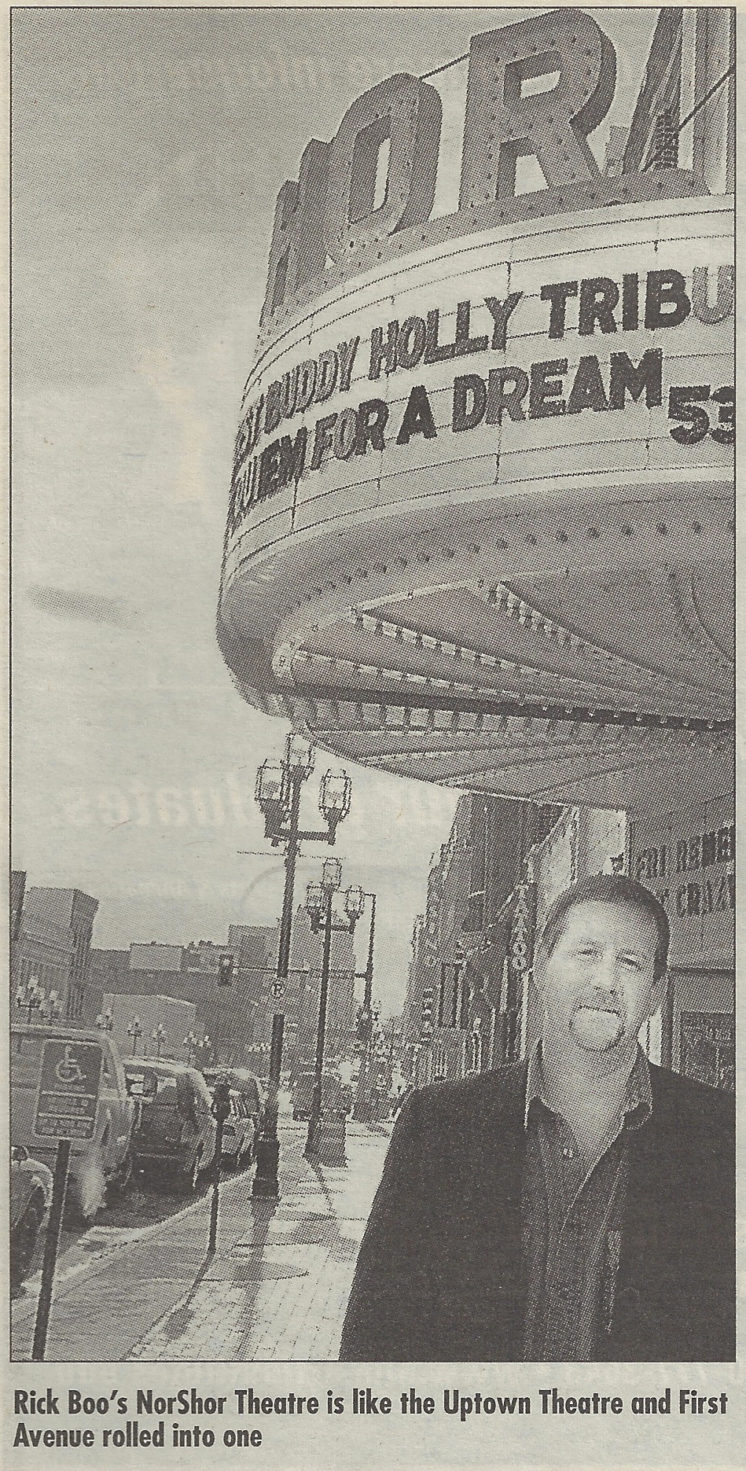

Besides, imagining alternatives to Duluth’s stark economic situation — the city has been losing population for some 25 years running — may be less an issue of “lifestyle” than a matter of civic survival. As the state steel industry does its impersonation of Pittsburgh in the Seventies, the search for some other local identity takes on new meaning. This would help explain why the sighting of two city-council members hanging out at the NorShor Theatre — sort of the Uptown Theatre and First Avenue rolled into one — might be seized upon as a sign that the revolution is nigh. The 90-year-old Norshor is a concrete metaphor for how art people know music people know political people in Duluth. By day it features an art gallery and art films; by night it hosts concerts on the elegant mezzanine. Remarkably, the key to the venue’s revival has been local music, which began rallying three years ago with the Homegrown Festival, organized by Starfire for his 31st birthday.

Duluth has since become almost giddy with its own momentum. It’s a feeling perfectly captured on a descriptively tagged new compilation, Duluth Does Dylan (Spinout), which features 15 active local bands and sleeve art by Chris Monroe. “Dylan’s our ticket,” explains the ever-frank Swanson. “He was born here, so we might as well use him to get noticed.”

Swanson says the music scene is better than it has been for 30 years, and he should know. He remembers attending dances at the National Guard Armory as a kid, the same place Dylan saw Buddy Holly before the 1959 plane crash. Swanson watched local rock ‘n’ roll sputter to life here in the Sixties, from the teenage Titans through such hippie bands as Trinity Freak. The antiwar counterculture left at least one enduring local institution: The Whole Foods Cooperative. But like a lot of residents, Swanson left when the going got tough in the Eighties, landing a $50,000-a-year job at a guitar company in L.A.

“I had to put up with too much corporate bullshit out there,” Swanson says of his L.A. years. “I came back and said, ‘Hey, the air is clean, there are no drive-bys.”” He has been here ever since he returned for a visit in 1990 and has lately been busy mixing yet another local CD, this one of live music sponsored by the Home Grown radio show on KRBR-FM (102.5).

Other people in this room have left and come back, like Chris Monroe, the cartoonist who took the death of the revered Charles Schulz as an opportunity to introduce a sphere-headed boy of her own who vomits up “gummi wrestlers” from the Walmart, only to see them lapped up by his dog “Snoppie.” A mother of a nine-year-old, Monroe strikes me as particularly in tune with little-kid belly laughs.

Speaking of, a knock on the door announces Low’s Sparhawk and Parker, who greet everyone while cradling their blanketed baby. They’re trailed by a reporter for the Star Tribune, who also happens to be my roommate in Minneapolis, Simon Peter Groebner. “Isn’t there some antitrust law against that?” Sparhawk jokes.

The general coincidence of this roommate reunion amuses everyone, and perhaps allows us to seem less like “big”-city media intruders. And though it’s my first visit to Duluth, I begin to feel at home. This is the “vibe,” I think. A moment’s pause from recording — and reporting — and the all-important end product suddenly doesn’t seem all that important.

If there is one certainty at the heart of Duluth’s mystique it is Lake Superior. The lake is always there and always cold. It will always be there and it will always be cold. Nothing about the physical landscape of the lake’s corner should make a visit this spring more pressing than one the next. In summertime the highway to the south will always feel like an ear-popping ramp into heaven. In winter, the endless rows of roadside birch will always look gray, like the dull edge of a spotlight on the earth. The hillside at the center of town will always be steep enough to allow downhill skiing on Lake Avenue.

Dylan couldn’t bring himself to face this hill again for most of his life, and a lot of residents speak of the panorama as if it were some sort of general reminder of our insignificance. “One of the many pleasures of living in Duluth is that you have to look at the lake a lot,” writes Barton Sutter in his 1998 book Cold Comfort: Life at the Top of the Map. “You might only mean to get some groceries or a hammer from the hardware store, but on your way you see something so grand, so terrible and beautiful, that you absorb your daily requirement of humility just by driving down the street … I finally realized that the lake was God.”

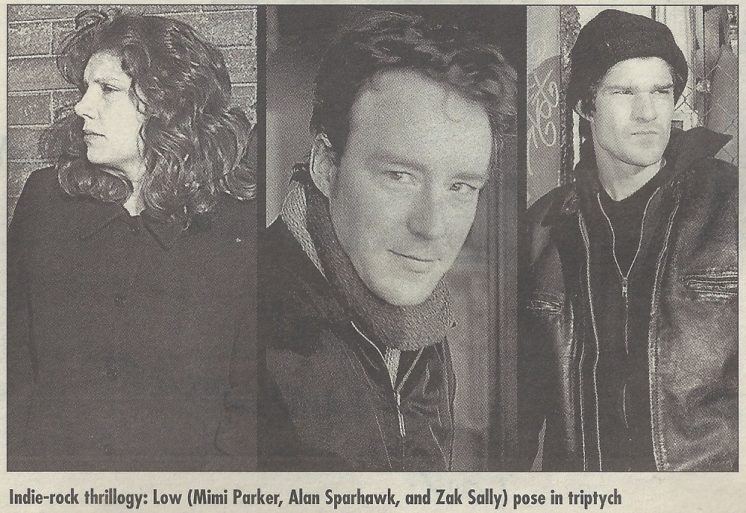

Certainly the thought must have crossed the minds of Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker, who reside in a modest brick-and-stucco house overlooking the neighborhood that probably qualifies as the town’s slum, with the vast lake looming beyond. You can see Superior from the kitchen, where a few Jesus postcards on the fridge offer the only outward sign of the house — hold faith: Sparhawk and Parker, who are married, belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Their only chemical indulgence is Toblerone, which Parker graciously offers before placing little Hollis Mae in a Jolly Jumper, one of those bouncing chairs suspended from the doorway’s arch by springs.

Shuffling quietly into the adjoining living room, the band’s three members gather to watch the caterwauling baby. Hollis announced herself ten months ago during a band rehearsal in the basement — that’s where Parker went into labor — and has been “singing” ever since. She may yet inherit her parents’ serenity and angelic curls, but for now she’s as thin-haired and loud as Ian MacKaye and seems ready to release all the rock ‘n’ roll energy Low have been sublimating for eight years. A week later, her vocal improvisations will be all I can discern on my interview tape.

In person, these musicians are as farmer-quiet, intelligent, and, ultimately, inscrutable as their famously glacial pop. Bassist Zak Sally, a dark-eyed Duluth native who has since moved to the Twin Cities, still retains a certain rural wariness. That this is the band that might put Duluth “on the map” may be hard to believe. Low’s use of stillness, their loud privacy, their elderly pace — all recall the suppressed passion of an Ozu film, hardly the new beat that’s sweeping the nation. Their response to the challenge of covering the hackneyed “Blowin’ in the Wind” on Duluth Does Dylan was to sing the words without the slightest inflection rather than take them into their mouths and personalize them. Their music is a lot like Lake Superior: a beautiful blank that withstands considerable projection from those observing it.

But I have little doubt that whatever God is, Low writes about it. No band is more suited to singing lines like “What is the whore you’re living for?” inside the Sacred Heart Music Center, the words hovering ethereally in the room. Even Zak Sally’s Chester Brown-inspired comic book, Recidivist, contains a tale of Dostoyevsky’s faith-reviving brush with the firing squad — and Sally would seem the most secular of the trio.

The arrival of Hollis might explain why Low sounds more musical — dare I say happier? — on the new Things We Lost in the Fire (Kranky), a chamber-pop opus augmented by strings, keyboards, horns, samples, and roomfuls of overdubbed Als and Mimis. Low is a production now. And in Minneapolis, the band will play its largest CD-release concert ever at the Woman’s Club Theatre on Thursday, February 8. Last year they collaborated with big names in drum ‘n’ bass Springheel Jack (call it poetic justice after the major label that dropped them released a remix album without Low’s participation in 1998), and soundtracked a Gap ad. They were more recently featured in Spin and GQ — coverage that Sparhawk jokingly attributes to the fact that their fans have gotten better jobs.

But it also occurs to me that the adults watching Hollis bounce seem to have welcomed an addition to an already good life, and that this life is inevitably bound up in the changing moods of Duluth. “Everywhere you go, there are people with bands,” says Sparhawk, tidying up the living room by returning baby toys and a copy of Wired to the designated mess of the band office. “And for some reason, lately, it’s really self-aware: Like, ‘Hey, we’re in Duluth!'”

Such pride seems to amuse Sparhawk and Parker: The place is home to them by force of habit, they say, not to mention the convenient proximity to parents, and a central location for touring. The singers get their fair share of the world on the road but say they miss sushi. If somebody opened a sushi bar in Duluth, Sally deadpans, the local news would run an item explaining what sushi is. Not that everyone in town is chafing at its limits.

“It’s close enough to Minneapolis that anyone who wanted to get out of here did,” says Sparhawk, smiling. “There’s not a feeling of, Oh, we’re stuck in this small town.”

In fact most natives, like Sally, move away. And who could blame them? When Sally was in high school, and Sparhawk and Parker were attending the University of Minnesota-Duluth together, his favorite driving song was Big Black’s “Kerosene,” a pyromaniacal rant against small-town life written by the Missoula, Montana, native who recorded most of Things We Lost in the Fire, Steve Albini.

Like a lot of artists who stay, Sparhawk and Parker originally came from even smaller towns — they graduated as high school sweethearts in a class of 28 students from Clearbrook. “I thought it was a big city when the first time I was downtown someone tried to sell me crack,” says Sparhawk. “I just thought, whoa, man, I am in the cit-ee!”

“Was it ____?” Sally names a mutual acquaintance, and everyone laughs. Although turning down a piece of the rock, Sparhawk and Parker seized on the small arty fringe already existing in Duluth. It seems significant now that Low formed in one housing co-op (the Emerson Tenants Cooperative still overlooking the lake) and played their first gig in another (the now defunct Recycla-Bell, a housing space in the old Bell Telephone Building).

Low’s start, in other words, was hardly filled with glamour and hype, which makes the band’s current slide toward celebrity all the harder to take. When the crew packs up Hollis to get dinner at Lake Avenue Café on the redeveloped, touristy riverfront, the waiter asks, “You’re the people who phoned in?” When I mention this apparently grudging behavior to Sparhawk, he responds quietly, “Oh, no, he’s just a big fan.”

Do a lot of people act strangely around the band now? “No,” Sparhawk says, “but we’ve had enough experiences where you could almost guess what it’s like being famous — how weird it is.”

The members of Low have never set themselves apart from their community, and Sparhawk even writes occasionally for the Ripsaw News. He enthusiastically recommends the columns of one Slim Goodbuzz, which always begin with the headline “Gettin’ Ripped at the … — and then name yet another bar where slurred high jinks have been witnessed and/or participated in. Identified in print only as “a resident of Central Hillside,” this “booze-scene” critic serves as a check on the palpable self-romance of the local arts community. Goodbuzz assumes the persona of the perpetually dissatisfied Bacchanalian overjoyed to find, for instance, a bar attached to a laundromat.

I can imagine Sparhawk eating this up: Mormons don’t drink, and I wonder if the Goodbuzz fan isn’t the same side of his personality that would dub himself Chicken Bone George and play distorted Muddy Waters tunes with his side band the Black-eyed Snakes — a sort of Sunday 3:00 a.m. to Low’s Sunday 11:00 a.m.

And speaking of the dark side, Sally tells me about something called “meat parties,” where men in drag get together, invite other men, and eat meat. He grumbles, tongue in cheek, that it took him until he was 26 years old to get invited to one. Is this the “vibe”?

No, Sally says — though his attempt to summarize Duluth is as vague as everyone else’s. “It’s not a city and it’s not a suburb and it’s not a small town,” he says. “It’s just sort of exactly what it is.”

А week later I’m in a van with Brad Nelson, drummer for Father Hennepin, and his brother Tim, guitarist for rap-folk rockers Gild. Brad and Tim sit in the front of the vehicle, wearing hats emblazoned with iron-on patches of the other brother’s band. They share red hair, sideburns, lankiness, and effusiveness. This last attribute makes them perfect tour guides.

Brad also happens to be the publisher of the Ripsaw News (oh, and also the drummer for the Black-eyed Snakes). Tim organized Duluth Does Dylan and co-owns Fitger’s Brewhouse. Next to me sits Ripsaw circulation coordinator Susan Stone, a quieter soul who will serve as designated driver later on. And in the back sits Slim Goodbuzz himself, whose identity I’m duly sworn to protect. The only feature I’ll give away is a steadfast ironic glint in sad eyes that might otherwise be given to disappointment — as if his blurred vision quest were doomed from the outset.

We are all following an old Duluth custom: hitting the highway at 12:30 a.m. on a weekend night to head over to Superior — the even rustier, less populated, more impoverished Wisconsin “sister” city, where bar time is 2:00 a.m. and where life’s anxieties are rendered blotto under the knowing, helpless eyes of mounted bears and elk. With its dubious billboard slogan “Next to Duluth, We’re Superior,” the second of the Twin Ports makes up for its inferior culture by having more fun. To get there, I’m told, you take either what’s called “the high bridge” or the Bong Memorial Bridge — the joke being, “If you can’t get high, go to the Bong.” But ask for directions and you’re a goner: In Duluth-Superior’s Bizarro World, east is north, and north is west.

And bongos are in. When we arrive at Norm’s Beer & Brats, a packed dance-floor’s worth of flesh-baring young liberal-arts students is screaming at tonight’s new-wave outfit, Ballyhoo, who are in the midst of a frenzied conga solo. Goodbuzz informs me that, for some reason, a lot of local bands favor extraneous percussion. Anything to get noticed, I suppose. Besides Low, the most famous band with roots in the area remains the Fuckin’ Shit Biscuits, whose very cognomen suggests a certain need to grab attention by its private parts. One local legend has it that when a pre-bankruptcy MC Hammer played Duluth in the early Nineties, the Twin Cities band Dogshine, whose members hail from the Twin Ports, printed up flyers saying, “Fuck MC Hammer, come see our show,” and slapped them up all over Hammer’s tour bus, later going so far as to phone the venue to make a bomb threat.

Around the time that I’m feeling driven to storm the stage, grab the mic, and wail out a version of “Kumbaya,” I meet one of the new twentysomething Duluth city-council members, Donny Ness, and begin to grill him about the remarkable turnout for Nader in northern Minnesota. Before we can really get into it, though, a busty waitress hands me something green with a plastic alligator in it and I find the drink mysteriously paid for. Everyone knows why I’m here by now, and the goodwill overflowing around the occasion — Brad Nelson’s 31st birthday — has begun running in my direction. Gradually, the green concoction does its brutal work.

… and I wake up the next morning to find this alligator staring at me, sitting on top of a beeping clock radio: 10:15 a.m. When I flop out of bed and down the stairs of the Nelson residence, Brad and Tim greet me with coffee and a bunch of local CDs. Apparently they are no longer affected by their own green drinks. Our designated driver, Susan, has nearly completed her managerial shift at the co-op, they say. So we have time to grab brunch before she shows us around. I feel like taping a sign to my throbbing forehead that says “slacker” and putting a bullet through it — or maybe consuming a scale of the alligator that bit me.

Today Brad and Tim are in full slacker-with-cell-phone mode. The slightly older, gaunter Tim has streaky blond highlights and an earring. Brad looks more boyish and neat; he has become a newspaperman. They take me to a greasy spoon called Uncle Loui’s Café, shed a layer, and climb into the booth facing the door.

“Uncle Loui’s is a rock ‘n’ roll institution,” declares Brad, adding more quietly: “You get to see who slept together the night before.” Later the door swings open and they both look up at once, as if the middle-aged waitress had posted a centerfold on the menu board. I don’t know what couple just came in, but the Nelsons look at each other as if to say, “So that’s who he went home with!”

These brothers and friends embody just how completely the Ripsaw and local music culture overlap. Everyone on the paper’s staff seems required to play in at least one band. And it’s telling that the very first issue ran a music column on the cover. When I speak to NorShor Theatre owner Rick Boo, he describes the Ripsaw benefit held at the theater last year as a general bohemian coming-together, with “improv-painting” and bands playing. Noise-rockers the Dames volunteered even after receiving a bad review. Now the paper depends on every corner of the arts community — not to mention the preservationist and environmentalist movements — for support.

These brothers and friends embody just how completely the Ripsaw and local music culture overlap. Everyone on the paper’s staff seems required to play in at least one band. And it’s telling that the very first issue ran a music column on the cover. When I speak to NorShor Theatre owner Rick Boo, he describes the Ripsaw benefit held at the theater last year as a general bohemian coming-together, with “improv-painting” and bands playing. Noise-rockers the Dames volunteered even after receiving a bad review. Now the paper depends on every corner of the arts community — not to mention the preservationist and environmentalist movements — for support.

“Duluth is still a lot of old money,” says Brad. “It’s built on timber and steel, and a lot of that money is still in those old families — it sort of hovers there. And I don’t really know how it all filters down, but it’s more far-reaching than we realize. When the Ripsaw first started, we sort of pissed off the establishment, and all of a sudden we were banned from all these hotels for distribution. People wouldn’t look at us for advertising because they were worried about reprisals from the city. Rick Boo at the NorShor was afraid to advertise with us because he was worried city inspectors would shut him down.”

“At the Brewhouse,” adds Tim, “we had electrical inspectors come in more frequently after we started advertising in the Ripsaw.” Brad says he heard that someone at city hall had called Allete, the power company where he coaches skiing, and urged that they dismiss him as a reprisal for his muckraking.

To understand how such theories could seem anything but far-fetched, it’s worth remembering Duluth’s history of class warfare: The place once had more millionaires per capita than any city in the world. After French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut (or Duluth), made peace between the Dakota and the Ojibwe in 1679 — cementing the deal with reciprocal marriages — the fur trade began in full swing. After that came the sawmills, the ports, the railroad, and the mines. By the early 1900s, the rich had begun building mansions on the Great Lake as monuments to their own permanence. Duluth boasted ten newspapers and six banks — and even its first skyscraper, the Torrey Building, where the Ripsaw relocated last month.

After breakfast, the Nelsons take me to the new office, which still has “Pinkerton’s, Inc.” painted on the door — the name of the security company descended from that old strike-breaking goon squad of yore. The rooms have high ceilings with giant cracks in the plaster — “the Bosnia look,” Brad jokes. On the floor sits a photocopy of the original Duluth Rip-saw, a local paper published between 1917 and 1926 by John L. Morrison. Although a notorious racist and puritanical Christian, Morrison crusaded against the corruption wrought by the railroad boom (and took the opportunity to extort money from potential targets while he was at it). Headlines such as “Corporations Seek Baxter’s Scalp” left no doubt where his class loyalties lay.

In a hilarious, anonymously penned account of his own arrest — a September 7, 1918 issue headlined “Captain Bruce Palmer is Rotten Dinner Host” (subhead: “Invites Morrison Home to Dinner Then Orders Him Jailed”) — he described an argument with a recently arrested saloonkeeper who objected to being publicized in the paper. “He called names and attacked Morrison’s business integrity,” goes the Onion-like prose. To which Morrison responded: “Do I owe you anything?”

The idea that the press owes business nothing is certainly part of the new Ripsaw’s spirit of practical defiance. The first breaking story about Mayor Gary Doty’s push for the Soft Center received the Morrison-worthy headline “Dotygate!” (Subheadline: “City administration attempts bribery?”) One subject in the story, A&L Development, threatened a lawsuit, then backed off. And to this day, Doty refuses to grant interviews to the Ripsaw.

“When we first started, people hated it because they wanted Minnesota Nice,” Brad Nelson explains. “And still, nobody wants to talk, because a handful of people hold all the cards, and if you piss them off they can really hurt you.”

This is every reporter’s dream, really — at least every reporter writing for an ostensibly alternative weekly. Duluth’s small-town politics have the effect of magnifying everything, including the reported word. A well-put sentence can spook the executives; a sharp editorial might shake city hall. Council member Russ Stewart once told the Ripsaw that he moved to Duluth “because it’s a funky, eclectic place with a bunch of artists and weirdoes.” I’m sure he never anticipated how much power those weirdoes, including him, might one day wield.

“I think the complexion of the city council changed a lot because we were there,” says Brad. “All the coverage that the Duluth News Tribune had given [the Soft Center] amounted to cheerleading. And we came along and poked holes in how the process had gone down — and the negative effects of destroying a square city block of historic buildings. It turned into a big issue during the mayoral race and city council race, and now we have Russ Stewart of the Green Party representing this Central Hillside district.”

In Duluth, lovers of new music and old buildings are natural allies. I’m not surprised to learn, for instance, that the same local gadfly, Eric Ringsred, who sued to save the Sacred Heart Cathedral, encouraged Brad Nelson and co-publisher/art director Cord Dada to start the Ripsaw in the first place. It follows, too, that when city officials recommended foreclosing on the NorShor — the business was late in repaying a low-interest loan from the Duluth Economic Development Authority, and one official had taken a fancy to the idea of a ballet house — the Ripsaw rallied to owner Rick Boo’s defense.

“All these things are more like a cooperative than businesses,” says Brad. “Everybody knows he’s not making money on this. And when the Ripsaw ran an editorial, someone called up and asked, ‘How much do you need?” As it happens, the theater has done well by local music in the past year, and paid its loan up to date in December.

Of course, there is always the danger that the new Duluth will become too friendly with itself, that the bonds of solidarity will become so tight that matters of aesthetic discrimination, not to mention reportorial objectivity, will become ethically squishy.

“It was easier when the Ripsaw started, because I was a nobody and everybody I knew was nobodies,” admits Brad Nelson. “Now my friends are assuming power — like Donny Ness. As you slowly become The Man, it becomes harder to attack The Man.” Hence, the paper has toned down its headlines and attack-dog posture. “Basically, if we were going to make this a viable business –”

“– you couldn’t have subheadlines like ‘Is the City Run by Nazis?’” I ask, picking up an early issue.

“Yeah, we had to take headlines like that out,” Nelson says, smiling.

Before I leave town, Brad and Tim want to make a pilgrimage to the Sacred Heart Music Center, the hundred-year-old Cathedral with a lawn mower in the confessional. So we drive up the hill to Second Avenue West and Fourth Street, where we come across a soft-faced woman sitting in the passenger side of a van, alone, with the motor running. She tells us the person we want is just locking up, but we catch him at the door, a pleasant and rotund man with a thick beard of gray.

John Ward is eager to show us the blue, white, and gold interior of the chapel, with its grand piano up front where a marble altar once stood. As we walk toward it, bathed in stained-glass sunbeams, Ward wheels around and points to the 30-foot-high pipes of the Felgemaker organ in the balcony. The mighty instrument was built right into the structure of the church, and that, he says, was what ultimately saved the place. But his take on the destruction of monuments seems practical. “I guess what makes places like this more valuable,” he says, “is people tearing them down.”

Low will play a concert here on Wednesday, February 7, and Ward reports that anything louder or faster than the slowest, quietest band on earth will just muddy up “the sibilants” — whatever sibilants are. But slow ballads work just fine with the room’s acoustics. And, to demonstrate, he sits down at the piano and gives us an impromptu performance, singing and playing at length to his surprised guests and the empty pews. It’s as if he has something he wants to reveal, and us being there is reason enough to do it. I don’t recognize the song as it cascades through the vaulted arches. Outside, the van is probably still sputtering exhaust, its passenger still seated patiently. But, in the practical scheme of things, what’s happening here this moment is as important as anything happening anywhere else.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

3 Comments

vicarious

about 4 years agoBuzzard

about 4 years agotoyota200x

about 4 years ago