Avant-Garde Women: The Hundred-Jointed Dancer and the Laban Ladies

Art history is weighted toward objects like paintings and sculptures, and so the performing arts have gotten less attention. Dadaism, which began in Zurich in 1916, was an art movement that generated objects — but it was also a highly performance-based phenomenon. The origin and center of Dada activity was in fact a rollicking cabaret. What happened on stage was every bit as important as the paintings on display; this also held true in the later Galerie Dada, which centered around performance-based “soirees.”

Art history is weighted toward objects like paintings and sculptures, and so the performing arts have gotten less attention. Dadaism, which began in Zurich in 1916, was an art movement that generated objects — but it was also a highly performance-based phenomenon. The origin and center of Dada activity was in fact a rollicking cabaret. What happened on stage was every bit as important as the paintings on display; this also held true in the later Galerie Dada, which centered around performance-based “soirees.”

A great number of Dada stage performers were women, but art history emphasized the artworks of the Dada men instead. This is slowly being corrected. The female dancers on Dada stages have been characterized as being “associated with” Dada; they have also been called “fringe” members. But the more I look into it, the more they seem like central players. These women were from the nearby dance school of Rudolph von Laban (pronounced like “Le Bon”); Dadaist Hugo Ball called them the “Laban Ladies.” Their star dancer was founding Dadaist Sophie Taeuber, who Ball called the “hundred-jointed dancer.” She was the only person with full membership in both groups, and it was through her that Laban Ladies filled Dada’s stages. Looking at connections between the Dadaists and these avant-garde women reveals: the Laban Ladies were Dada’s secret weapon.

Dance Denigrated as a Trivial Women’s Art

It irritates me to read, more than 100 years after the fact, that the argument over the Dada women persists. From the “Sex and the Cabaret” paper by Ruth Hemus:

The fate of Dada’s dancers in accounts of the movement has been paradigmatic of the fate of women artists and writers excluded from histories of art and literature .… some materials chosen by women (handicrafts for example) or art forms (dance) are considered less appropriate or trivial … women’s lives are analysed more than their work … women’s concerns are labelled ‘personal’ or ‘intimate’ as compared with some elusive male standard … Whilst dance was central to the atmosphere, practices and appeal of the cabaret, its potential as an experimental art form was not fully realised either by Dada protagonists at the time or by critics at a later stage and this, in large part, because of attitudes towards women, the female body and sexuality. Dance has been perceived as peripheral to ‘real’ Dada concerns, rather than integral, Dada’s dancers as less noteworthy than Dada’s painters and poets, and Dada’s women then — and now — as ‘other’ to Dada’s men.

For example, in Dada’s seven-person inner circle were two women, Emmy Hennings and Sophie Taeuber. They were both primarily performers, although each had multiple artistic talents. And in each case, these women’s status as “founding members of Dada” is most often put into question.

The denigration of women’s arts and materials includes dance and textiles in Taeuber’s case; and the cabaret routines (including dancing) in Hennings’ case. But both women were experts at captivating crowds, which cannot be underscored enough. Dada was performative at its core: Hennings and Ball had founded the Cabaret Voltaire which kicked it all off — the foundation of the cabaret was Hennings’ songs backed by Ball on piano. Some even say the idea to start the Cabaret was Hennings’ to begin with, which by one measure would make her the Dada founder. It is ridiculous to diminish her status because she was a performer instead of a painter. She should be elevated and recognized as absolutely central. (More about Hennings in the next installment of this series.)

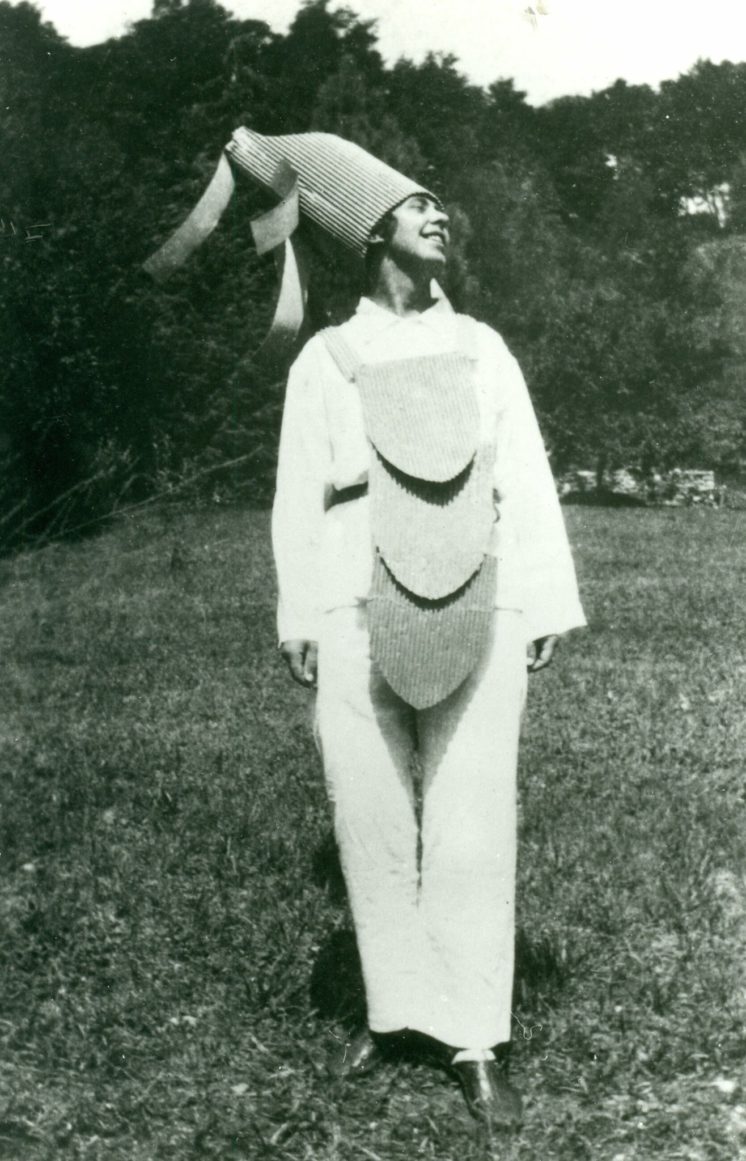

Taeuber’s centrality to Dada also needs to be recognized, as I argued in a previous essay, strictly on the basis of her artwork. But Dada events featured much dance and Taeuber did a lot of it. She was iconic. Art and dance historians are still talking about one of her dances, a performance which lasted a few minutes, more than a century ago. She wore a mask and a restrictive costume, and danced to Ball’s sound poem “Song of the Flying Fish and the Sea Horses” (see below). If the Dada events had been videoed, my assumption is we would gain an immediate appreciation of the huge role played by Taeuber and the other Laban Ladies.

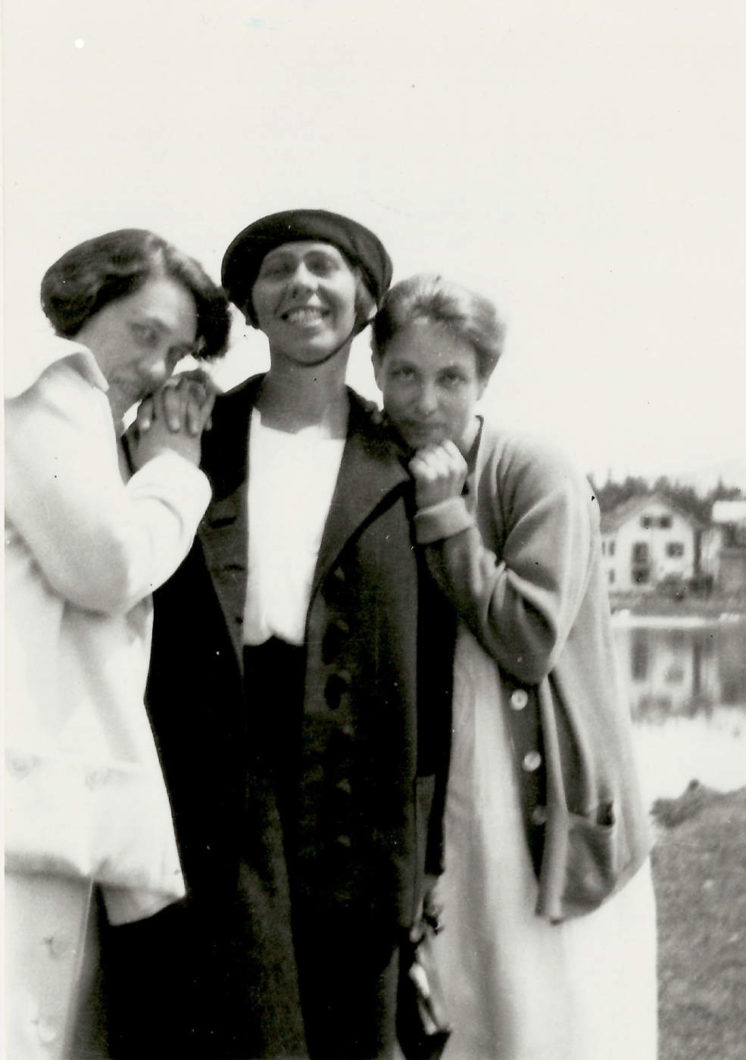

Mary Wigman, Sophie Taeuber, and Berte Trumphy, 1918.

Dada Needed Dance

According to the article “Zurich Dada and Dance: Formative Ferment” by Naima Prevots, Dada had “a profound effect on twentieth-century dance, bringing new possibilities to a rapidly changing field.” The paper notes there were two types of “dance activity” going on: “One was the movement exploration that happened as a component of the experiments with sounds, words and masks. The other aspect of the dance activity consisted of the movement ideas presented in more formal dance compositions, performed and choreographed by women studying with Rudolf Laban.”

The way I look at it is, the Dada men as untrained “dancers” were essentially goofing around, in keeping with the Dada spirit of zany irreverence. And this was balanced with, and in tension with, the highly-trained Laban Ladies performing expressionist modern dance — which would have seemed new and strange to audiences. Thus the Labanese style was quite at home at the cabaret. But as Hemus writes of the academic response, the two types of dance represented an “opposition … not only between expressionist and dadaist concerns, but also between male and female dance performances. The implication is that women’s dances were not ‘edgy’ and ‘anarchic,’ and not quite Dada.” In other words, early scholarship about Dada ignored or downplayed the women’s contributions. But eventually the contribution of the Laban Ladies became unignorable. It may not have been “strictly Dada” (a definition with a male bias), but it was avant-garde AF.

And there was a mutual influence and benefit between Dada and Laban. But, as Hemus breaks it down, history cut against the women:

The connections between Laban and Dada might be fêted as mutually productive … With Taeuber acting as a bridging-point between the Laban school and the Cabaret Voltaire, dance became a component of soirées in the spring and summer of 1916. By the time of the establishment of the Galerie Dada, Laban dancers, too, were taking part in Dada soirées, alongside untrained [male] dancers like Ball, Huelsenbeck and Tzara. A comment by the [Laban] dancer Käthe Wulff testifies to an active dialogue: ‘If someone wanted to do a dance, for example Sophie Taeuber, I would have her show me the dance and discuss it with her.’ Here was an opportunity for the Dadaists to reach into another area of the ‘Arts with a capital A’, to both interfere irreverently with a traditional art form and to discover more about the potential of stage performance to jolt the expectations of their audience … Masks were similarly Dadaist in this respect. Wulff recalls, ‘A new addition was the masks: that belonged to the group, to us and to the time.’ And Ball writes: ‘What fascinates us all about the masks is that they represent not human characters and passions, but passions and characters that are larger than life.’ The dancers’ masks and costumes, as in the photograph of Taeuber, are discomfiting, their effect contrasting starkly to the traditional European aesthetic of dance. Why, then, should Laban’s dancers and Taeuber fall into a different category from Ball and Huelsenbeck, dancing to their drums? It may be that this is an issue of reception, whereby women’s activities and women on stage are perceived differently from men: the men are ‘at play’; the women are being ‘expressive.’

I think that’s exactly it. This video below features a rough re-creation of a typical Dada-style cabaret performance:

This was produced years after the fact by unaffiliated persons for educational purposes; for one thing it is clearly in studio; the actual cabaret would have had a riotous, interactive audience. At the 1:30 mark, note that the men are accompanied by a pair of ballerinas; these represent the Laban Ladies. Granted the re-creation deals in generalities, but you can see what Hemus is talking about: the men are “at play” while the women are “expressive,” yet the performance as a whole relies upon the tension between the two types of “dance activity.” The interplay ultimately defies rational analysis, and thus it is “strictly Dada.”

Laban’s teachings bordered on the Dadaistic in their own right. For instance, if Ball’s sound poems were experiments in divorcing sounds from their meanings, compare that with this account of a Labanese exercise: “More advanced courses involved words and simple sentences, and some lessons grew to include improvised singing. Sometimes, ‘Laban made up the words to which we moved,’ or the students made use of ‘phrases, small poems that [they] composed together,’ suggesting a clear genealogy back to the work of Dalcroze [another pioneer of modern dance whose students frequently found their way to Laban]. These experiments occurred in largely improvisatory gatherings, held in darkness. As [Laban Lady Suzanne] Perrottet paraphrases it, Laban directed them: ‘Now we will choose a word, and pass it back and forth among ourselves and make it into a musical theme.’”

Ball’s bizarre sound poems would have made the Laban Ladies feel right at home, and they would have been trained to dance to them effectively.

Another point of connection is mentioned by Prevots when she argues: “Laban may well have fully developed his theoretical material without the presence and ideas of Sophie Taeuber and the other Zurich Dadaists. However, he was working with movement in a new and different way and it would seem likely that both his own early training in art and architecture [was] compatible [with the] simultaneous investigations of Taeuber, Arp, Janco and others connected with Zurich Dada [like the Laban Ladies].”

In April 1917, Hugo Ball wrote in his journal about working hand-in-glove with the dancers:

Preparations for the second soiree. I am rehearsing a new dance with five Laban-ladies … in long black caftans and face masks. The movements are symmetrical, the rhythm is strongly emphasized, the mimicry is of a studied, deformed ugliness … ugliness awakens the consciousness and finally leads to recognition — of one’s own ugliness … Our present stylistic endeavors — what are they trying to do? To free themselves from these times.

The Dadaist Hans Richter wrote in Dada: Art and Anti-Art of the final soiree:

The ballet Noir Kakadu, with Janco’s [African-inspired] masks to hide the pretty faces of our Labanese girls, and abstract costumes to cover their slender bodies, was something quite new, unexpected and anti-conventional.

Dada needed dance, and dancers. Trying to “free themselves from these times,” together they created “something quite new” i.e. avant-garde. And it lasted — some aspects of the Dada-Laban fusion are still with us. As Hemus writes:

Dance offered the Dadaists huge potential: to explore ‘primitivism’; to break with tradition in an art form that was severely restrained by expectations; to democratise dance (anyone should try it); to exploit the fact that it is unmediated by the worn-out language of words; and to communicate directly and physically with the audience. Taeuber, in particular, recognised this potential. Moreover, she could act with comparative autonomy, possibly because it was not an art form in which the men had any experience … The body as the artist’s tool or material anticipates later modern and postmodern performance where the body becomes the artwork, and the performance space the artwork event.

Second and third from left: Suzanne Perrotet, Kathe Wullf. Far right: Rudolph von Laban. Location is the Laban dance school at Monte Verita.

Laban

From 1913-1918, Rudolph von Laban founded and ran his School for Art; his focus shifted to dance and he referred to the school as his “dance farm.” This was located at Monte Verita near the Swiss village of Ascona. The Laban Ladies included his assistant Mary Wigman, dancer-musician-composer Suzanne Perrottet, and Katja Wulff (all of whom eventually started schools of their own), and others. This period has been called “the birth of modern dance.” Since 1900, Monte Verita (“Mount Truth”) had housed the “Co-operative vegetarian colony Monte Verita.” This was, not to mince words, a vegetarian free-love sunbathing nudist colony. The site became popular with anarchists, feminists, and artists, including the Dadaists.

Laban found people looking for a kind of freedom that his liberating dance techniques could provide:

Laban, the rebellious, charismatic son of a general, described the ‘dance-farm’ he established there as his ‘little kingdom’; he would summon his followers each morning by sounding a gong, and they would garden, cook, weave, and make their own clothes, costumes, and sandals. In Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935, the historian of dance Karl Toepfer writes of the radical, frenzied style … that Laban and his group pioneered: ‘German dance equated the liberated body not with an enhanced power to signify a wide range of emotions but with the power to signify and/or experience a single, great, supreme emotion: ecstasy. The basis for a free and modern identity lay in that most difficult to feel of all emotions.’ Ecstasy was seen as a tool to shatter bourgeois conventions, to return the alienated, mechanized modern subject back into harmony with the body, nature, and the unconscious rhythm of life.

One of Laban’s core principles was that dance existed independently of music. It was not opposed to music, but if you looked at dance as its own thing entirely, it didn’t need music. As stated in this lecture, Laban and others were trying to liberate dance. Traditional ballet subordinated dancers to the music, where the dancers’ job was to illustrate it. Laban on the other hand wanted dance to explore “what it means to be a body in space,” i.e., it shouldn’t matter if music is playing or not. Dance was not about music, it was about movement. This turned the notion of dance on its head, making it a co-equal to music and other arts, not subordinate to it. This was revolutionary at the time, and it marked an important evolutionary stage in the development of modern dance. Laban’s techniques produced dance that was weird, haunting, and sensual. Therefore Laban-trained dancers were ideally suited to be on the program at Dada events. And they were uniquely qualified to dance in performances without music, such as when Taeuber danced to Ball’s sound poems. Laban’s methods supercharged his dancers’ ability to perform without conventional trappings.

Laban branched out from Monte Verita to found the experimental ballet school in Zurich. He performed in the city with his students. One of his innovations was the “movement choir;” another was his dance notation, still in use. Often Laban’s students danced to his atonal compositions, but the students also worked with other Zurich artists and performers. If Laban students weren’t on stage, they were likely to be in the audience supporting each other or just enjoying the arts.

The journalist Claire Goll noted at the time:

The musician Laban had started a dance class … Sophie Taeuber, Arp’s girlfriend, danced there, and all the ballerina fanciers danced along behind.

Through Taeuber, the Laban Ladies and Dadaists joined forces:

Laban’s dance students, together with the Dadaists, organized choral festivals, masquerades, and other events during the summer months.

Ball notes in a journal entry from April 2, 1916, the Cabaret audience that night included “Mr. von Laban with his ladies.

For a cabaret that was only open a few months — which turned into a gallery series that ran for 11 weeks — the Laban Ladies were all over the performance world of the Dadaists. Not to put too fine a point on it, but I myself have done Dada-flavored events and trust me, you need dancers. Through Taeuber, the Dadaists had access to a troupe of some of the most experimental dancers in the world. They were so important to Dada that the 1974 introduction to Ball’s autobiography Flight Out of Time recognizes the Laban Ladies as Dadaists, albeit at a “fringe level … where Dada ended and Zurich at large began.”

But I think this understates the case. The Laban Ladies should be promoted from “fringe” members to full-on, established Dadaists, without whom Dada would have been irretrievably different. Dada would have been more still, less electrifying, and less influential.

The names of the Laban Ladies I have found in Dada literature are (with varied spellings as some anglicizations are evident): Sophie Taeuber, Mary Wigman, Berte Trumphy, Claire Walter, Suzanne Perrottet, Maria Vanselow, Ludmilla Vachtova, Käthe Wulff, Maja Kruscek, Maya Lenares, Raya Belensson, Jeanne Rigaud, and Maria Cantarelli. It was a pan-European student base including East Europeans, Russians, and women of color.

The Sex

Some Dada-Laban scholarship argues that the dancers’ artistic contributions to Dada have been overlooked because the women were written off as sex objects. For instance Hemus writes:

Hans Richter’s memoirs, in particular, suggest that gender was a powerful factor in the reception of the dancers. According to his accounts in Dada: Art and Anti-Art the male Dadaists viewed the Laban school dancers chiefly as potential, or in fact actual, sexual conquests. Richter writes: ‘If the [Café] Odéon was our terrestrial base, Laban’s ballet school was our celestial headquarters. There we met the young dancers of our generation: Mary Wigman, Maria Vanselow, Sophie Taeuber, Susanne Perrottet, Maja Kruscek, Käthe Wulff and others. Only at certain fixed times were we allowed into this nunnery, with which we all had more or less emotional ties, whether fleeting or permanent.’ Richter makes a clear distinction between the Odéon, (a forum for camaraderie and intellectual discussion) and the dance school: a feminised, sexualised arena. His references to the heavens and to a nunnery call on feminine stereotypes of angel and nun, and contrast with the women’s actual existence as corporal and sexual human beings. He writes about love affairs between the dancers and male Dadaists (Maja Kruscek and Tzara; Maria Vanselow and Georges Janco; Maria Vanselow and himself) declaring finally: ‘[Dadaist Walter] Serner, on the other hand, fickle as he was, did not like to pitch the tents of Laban (or anything else) in these lovely pastures for too long at a time. Into this rich field of perils we hurled ourselves as enthusiastically as we hurled ourselves into Dada. The two things went together!’ The equations are staggeringly unequivocal: using a decidedly macho metaphor, Richter declares that Dada, masculinity and sexual conquest go together. Of course it can be argued that this activity has nothing to do with dadaist cabaret activity, but already we note that Richter fails to go into any detail about the potential of working with ‘the dancers of our generation.’

I would argue that while the above is certainly true, it is not the whole story. For instance, the notion that Richter would be giddy about sexual relationships with beautiful dancers is not in itself disrespectful per se. While one can’t disentangle his attitude from his male privilege and his male gaze — nor mine — his comments are juvenile, but not crude or vulgar. They strike me as merely sex-positive. In addition, I do not believe he should be dinged by Hemus for “failing to go into any detail about the potential of working with” the Laban Ladies, since the list of things he fails to mention is infinite. Rather I would note, they were working together, and it is positive that he praises them as “the dancers of our generation.”

I would also attribute more sexual agency to the Laban Ladies than Hemus does. These adult women were entirely unencumbered by Victorian morality. They were utterly modern feminists drawn to the Laban school in part because of its origin at a free-love nudist colony. Even though we can pick apart Richter’s “less measured” comments for their patriarchal underpinnings, the sexy time between the Laban Ladies and the Dadaists strikes me as beautiful and natural and good. It was part of the overall exchange, interplay, and influence between the two groups. What performances were brainstormed during pillow-talk, I ask myself.

That Laban was boning, like, half his students is far more problematic, because of the power relation between student and teacher. There is a certain cultish, harem-like flavor to this handsome, charismatic man with his dance school, among whom I believe at least three students became mothers to his children. So if anything, that is where a pretty stark analysis of sexual power relations could be made, as opposed to the relatively innocent-sounding fun of sharing beds with Dadaists. Even in Laban’s case, I have not seen evidence that he was controlling anyone’s sexuality; everyone was apparently free to bed whomever they chose. The overwhelming impression I get is of a sexually empowered attitude among this group of very early feminists.

Some prominent Laban Ladies in Dada are profiled below.

Suzanne Perrottet

Suzanne Perrottet

The Swiss Perrottet trained as a violinist before studying dance and movement. First she studied with Dalcroze (who invented the “eurythmics” method, a way to integrate the learning of dance and music). Eventually her pursuits led her to Laban. Several Laban Ladies went from Dalcroze to Laban, a pipeline of progressive modern dancers. Perrottet performed several times at Galerie Dada events, the “soirees.”

For instance, the second soiree on 3/29/1917 at the Galerie Dada not only featured Taeuber dancing to Ball’s sound poems in the Janco mask — a legendary performance analyzed below — but “Mme. Perrottet” played “new music.” She also performed at the third Dada soiree on 4/28/17; the program for that night listed “S. Perrottet: Compositions by Schonberg, Laban, and Perrottet.” Wigman was mentioned as audience member on both nights, and Laban on at least one of them. Perrottet also performed at the eleventh and last Zurich Dada soiree, and likely additional ones I can’t verify. Perrottet composed for piano and violin. Influenced by Schonberg, an atonal composer whose music she was also performing, Perrottet’s music was atonal as well. And according to the article “Dance, Sound, Word: The ‘Hundred-Jointed Body’ in Zurich Dada Performance,” by Catherine Damman:

Perrottet’s influence — she was a trained musician and composer — even led Laban to experiment in musical composition, a fact that evidences Laban’s own interest in the possibilities of sound, not just as subsidiary accompaniment to dance movements but rather as artistically significant in its own right. In fact, Perrottet played Laban’s atonal compositions at the Galerie Dada on April 28, 1917.

As an atonal composer and a Labanese dancer on Dada stages, Perrottet was at the edge of the avant-garde. She said of her involvement in Dada: “I wanted to get away from harmony, from a consistent style … It just didn’t work for me any more. I wanted to screech, to fight more.”

After World War I ended, she went on to take over the Laban school in 1918 and renamed it after herself. She is considered one of the co-founders of modern expressionist dance along with Laban and Wigman.

Upon her death was discovered her archive of tens of thousands of photos she had clipped from magazines and newspapers, cataloging the range of human movement and expression. She was “an obsessive recorder of the physical possibilities of the human body.”

Mary Wigman

From “Dance of the Century” @1:49-3:15:

Mary Wigman went to meet Laban … Wigman became his pupil and then his assistant. Laban needed a student to challenge him. This Mary Wigman did, and they began a period of intense experiment. Laban and Wigman were at Monte Verita until … war broke out. Then they moved their school to Zurich, where it shared quarters with the Dadaists … Wigman created a strange echo of the Dadaists’ own research. For her it was a question of creating a discourse where the communicative strength lay not in a grammar, but rather in a rhythmic pulse. The [Dada] artists met at the Café des Banques, the precursor to the Cabaret Voltaire, where Mary Wigman often performed.

June 1916: At Ball’s legendary performance with Taeuber, he mentions seeing Laban and Mary Wigman in the audience. Her attendance at Dada performances was typical. As Laban’s assistant, his dancers were her dancers too.

The Laban school and Dada shared an enthusiasm for masks and masked dancers, and after she started her own school, Wigman continued the practice of using masks in dance performance. It’s difficult to sort out who influenced who. On the importance of masks, in the video below @10:00 Wigman says, “The mask knows transformation and horror. It changes throughout the dance. It breathes and lives like a frozen face within its form.”

Ball’s journal entry of 3/18/17 notes: “Last Sunday there was a costume party at Mary Wigman’s.” At the party, art critic Lucien Neitzel read Arp’s poems which everyone was hearing for the first time; it was a dry run for an upcoming performance at the Galerie. The Dadaists were going to parties at Wigman’s house which was full of Laban Ladies, and art was on the menu.

Kathe Wulff

Wulff was initially a gymnast. From there she studied dance, and then modern dance at the Laban school. She and Suzanne Perrottet founded a school teaching the eurythmy of Dalcroze. Dancer Mary Delpy said of Wulff “she walked like a queen, had perfect posture, and continued to teach beyond the age of 90.” She died in 1992 aged 101.

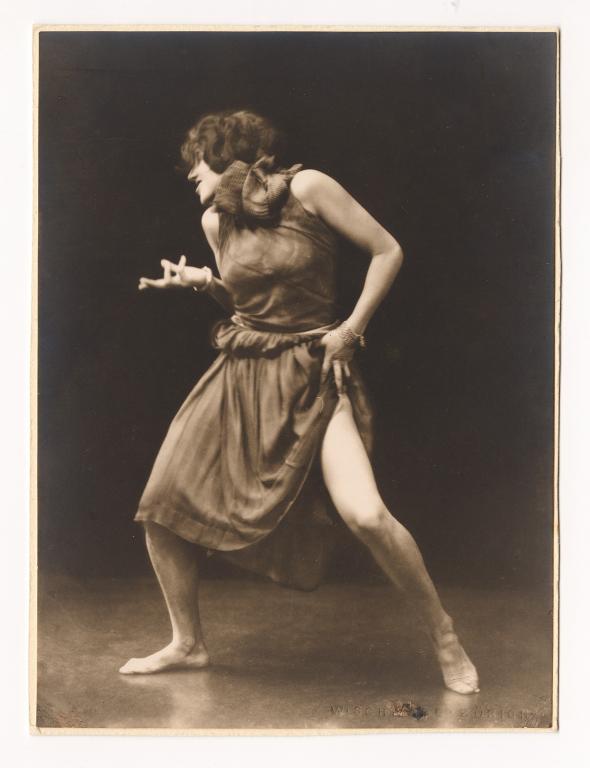

Sophie Taeuber, the “hundred-jointed dancer,” dancing to a sound poem by Hugo Ball at the Galerie Dada, Zurich 1917. The mask, by Marcel Janco, was painted with ox blood.

Sophie Taeuber, the Hundred-Jointed Dancer

And then there’s Taeuber. Her epic dance to one of Ball’s sound poems, “Song of the Flying Fish and the Sea Horses,” has become a cipher for the entire scope of the Dada-Laban Lady connection. One of the great tragedies of art history is that video did not exist in 1917 to capture the moment. But many Dadaists wrote about this performance, and many art and dance scholars have analyzed what it might have been like, in an almost desperate yearning to recreate it.

In Isabel Wünsche’s article “Exile, the Avant-Garde, and Dada: Women Artists Active in Switzerland during the First World War” we read: “At the opening of the DADA Gallery, in March 1917, Taeuber danced to verses by Hugo Ball, wearing a shamanic mask by Marcel Janco.” Hemus notes the mask was “painted with ox blood.” Note that her costume also contains a face.

The Taeuber online exhibition states:

The most famous image we have of her, from 1916, shows her midway through a dadaist dance at the Cabaret Voltaire [this is likely incorrect, most sources say the photo is from the 1917 Galerie Dada performance]. She is wrapped up in an absurdist costume, her hands sheathed in gloves and her face concealed behind a Marcel Janco-designed mask. Sophie Taeuber … was dancing to a recitation of Hugo Ball’s poetry. Her act was just as much a pillar of dada as Janco’s designs and Ball’s words, albeit one that lacked their concrete, recorded form. This moment stands as a spectral forerunner of performance art.

Ball himself wrote of the performance in his journal: “A poetic sequence of sounds was enough to make each of the individual word particles produce the strangest visible effect on the hundred-jointed body of the dancer.”

Ball also said her dancing was “tragic-absurd,” which is echoed in this paper: “She embodies the absurd, and thereby might more viscerally communicate the tragicomic sentiment particular to wartime Dada.”

According to Catherine Damman’s paper “Dance, Sound, Word: The “Hundred-Jointed Body” in Zurich Dada Performance:

Only a month prior to the presentation of Laban’s [Perrottet-inspired] atonal compositions, Taeuber graced the Galerie Dada stages with her memorable dance to Ball’s poems. Both original and striking, her performance compelled numerous figures to record their thoughts and reactions, often years later, and many of them in direct conflict with one another. Though Ball’s later-published diary entry recalling her performance is perhaps best known, another related essay of his, ‘Über Okkultismus, Hieratik und andere seltsam schöne Dinge’ (On the Occult, the Hieratic, and Other Strangely Beautiful Things) appeared in the Berner Intelligenzblatt on November 15, 1917, just a few months after he departed from the Zurich Dada group. Celebrating the talent of three female dancers, Ball discusses Wigman and the Russian dancer Raya Belensson before sharing a version of his notes on Taeuber, which I reproduce here in full:

“Sophie Taeuber is entirely different again. With her, in the place of tradition steps the light of the sun, the miracle. She is full of invention, caprice, the bizarre. In a private Zurich gallery she danced the “Song of the Flying Fish and Sea-Horses,” an onomatopoetic series of sounds. It was a dance full of spikes and fish-bones, full of flickering sun and gloss and of cutting sharpness. The lines shattered at her body. Every gesture is ordered in a hundred parts, sharp, light, pointed. The folly of perspective, of illumination, the atmosphere becomes here, for a hypersensitive nervous system, an occasion for drollery, for an ironic quip. Her dance formations are full of the desire to fantasize, grotesque and enchanted. Her body is girlishly clever and enriches the world with every new dance that she allows to happen.”

… Alternatively, Hans Arp would later recall Taeuber’s dancing body not as a mechanical object at the mercy of some external force but rather as an aggressive force itself, describing ‘the piercing glare’ and ‘the startle and the bite.’ Thirty years later, Marcel Janco still vividly remembered Taeuber’s ‘jerky syncopated expression,’ describing her movements as ‘exactly like the chords of good jazz or the restrained and dignified sadness of American blues.’ Janco’s allusion to new musical styles emphasized the modernity of Taeuber’s dance by dint of association. In contrast to Janco’s characterization of the dance as ‘jerky,’ and as ‘ke[pt] clear of all contrived elegance,’ Hennings [a dancer herself] remembered Taeuber as having natural beauty and grace, writing, ‘the ineffable softness of her movements allowed one to forget that her feet even touched the ground.’ In Hennings’s recollection, Taeuber’s dancing was akin to elements from nature: birds, flowers, stars, all of which seemed to be harmonious.

… Tzara’s description of Taeuber dancing, published in the first issue of his journal in July 1917, alongside mentions of Wigman, Perrottet, Wulff, and others. Tzara also identifies vibration as a key element, albeit in a more pathological sense, writing: ‘delirious bizarreness in the spider of the hand vibrates rhythm rapidly ascending to the paroxysm of a beautiful capricious mocking dementia.’ For Tzara, Taeuber’s dance was creaturely, even disordered.

A more scholarly take on reconstructing Taeuber’s dance, based on Laban principles, sounds like this: “Taeuber might have adapted [Laban’s] movement theory to her Dada costume as it enclosed and extended her body. The effect of her awkward collision with space would be based on a meticulously gauged environment in which the forms on and of her body make contact with the world through movement. Space would be conceived, as in Laban’s geometric principles, as a multiplanar icosahedron, and the dancer’s body the fourth-dimensional constituent that helps to articulate an understanding of the whole.”

Or, as the Laban Lady Ludmilla Vachtova put it, Taeuber “learned dance with Laban not as chance improvisation but as a creative game with variable rules that unfolds in time and space as a unique, moving, ephemeral sculpture.”

Emmy Hennings went on to write: “‘I can still see Sophie Taeuber-Arp dancing at the Galerie Dada. There several dancers who went on to become famous, such as Mary Wigman, showed us their talent. But none of them left us with such a vivid impression as Sophie Taeuber-Arp.’ …. There were many in the Dada group who thought Taeuber would go on to have a brilliant career as a dancer and choreographer.”

So according to Hennings, even though among the Laban Ladies were some of the pioneers of modern dance, Taeuber was the best dancer of them all. I have lost the reference but I read somewhere that Taeuber received star-level applause. She could have easily started her own dance school like Wigman and Perrottet and Wulff. Instead, she gave up dancing to pursue visual art more completely.

But elements of dance and movement can be found all through Taeuber’s artwork. She left dance, but dance never left her: “Even when engaging with seemingly static media such as drawings, painting, tapestry and embroidery, Taeuber often referred to the kinetic potential of dance. As such, not only her dance performances, but also her so-called applied arts are full of dance and movement. As Hubert observes in her drawings: ‘the harmonious distribution of Sophie’s lines, their unnerving flexibility, their modulations and rhythmicality, their refusal to pose vertically within the frame, in sum the graceful traces or designs they inscribe on the paper surface are features pertaining to the world of dance.’”

More Avant-Garde Women in this series:

–Eliane Brau: The Invisible Icon

–The Shakespearean Tragedy of Peggy and Pegeen Guggenheim

–Michelle Bernstein: Queen of the Situationists

–Sophie Taeuber: Founding Dadaist

–Emmy Hennings: “Shining Star of the Voltaire”

–Review of the Novel “Branded” by Founding Dadaist Emmy Hennings

An index of all Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments