Avant-Garde Women: The Shakespearean Tragedy of Peggy and Pegeen Guggenheim

The story of Peggy and Pegeen Guggenheim, as told by the Situationist painter Ralph Rumney, reads like Shakespeare: court intrigue, backstabbing, madness, and suicide. Rumney’s book The Consul provides a critical point of view on this fraught mother-daughter relationship cracking up at the cutting edge of the art world.

Peggy Guggenheim was the art collector-financier whose vast contribution to modern art resists calculation. For one thing, she saved many artworks (and artists) from extinction as the Nazis swept through France, shipping her collection of priceless art to safety through sub-infested waters. Then in the post-war years, her money and prestige powered the international art scene, as documented in the movie Art Addict. Peggy’s outsized personality and excesses are well known, as are her multiple liaisons through the art world; it’s scandalous and titillating. Not an artist herself, she had the foresight to grasp the importance of the avant-garde zeitgeist of the 20th Century. As art became less figurative and more experimental, not everyone could see the importance of what was occurring on canvasses worldwide. But Peggy got it. She blazed trails to preserve and display it. Her collection itself has been described as a work of art.

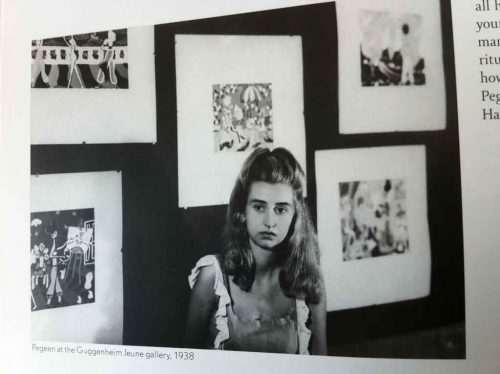

Art Addict devotes some time to Peggy’s daughter, Pegeen Guggenheim Vail, an accomplished surrealist painter in her own right. Peggy admits onscreen to being a hapless and emotionally ill-equipped mother. She also describes one of Pegeen’s suicide attempts which interrupted a dinner party with blood everywhere.

Pegeen Guggenheim Vail

Pegeen’s lifetime of depression was punctuated by more or less constant suicide attempts, one of which eventually succeeded in 1967. Art Addict documents that Peggy blamed Pegeen’s second husband – Ralph Rumney, whose name flashes across the screen as Peggy calls him terrible.

When Rumney died in 2002, The Guardian’s obituary said:

“He was, unforgivably, accused of murder. In 1967, Ralph’s wife Pegeen – whom he had saved from earlier suicide attempts – killed herself with an overdose of barbiturates in their Paris flat. Her mother, Peggy Guggenheim, who had always hated Ralph (for reasons he describes, with wit and a surprising lack of bitterness, in The Consul), took out a civil action against him for murder and ‘non-assistance to a person in danger’. Already devastated by the loss of his wife, Ralph endured months of persecution before the action was dropped.”

But Peggy had successfully smeared him. Ill-will followed him for decades. Here is Marlene Strauss’ 2017 lecture on Peggy’s history and legacy which characterizes Pegeen’s suicide solely as a function of her “troubled second marriage.” It is a simplification that gives Peggy cover for her own role in Pegeen’s suicidal depression.

Rumney and the Guggenheims

The Consul is a book of interviews with Rumney conducted by Gerard Berreby. I bought it because before he had any association with the Guggenheims, Rumney was an important figure in Situationism, an anti-art art movement in the lineage of Dada. Really I should call him an ex-Situationist, because Guy Debord kicked him out of the group — but Debord kicked everybody out. (I look at Situationism like the CIA — you never really leave it.)

As a Situationist, Rumney helped pioneer psychogeography, an imaginative critique of architecture and city planning which has propagated and remains influential. As a painter, Rumney was basically an abstract expressionist. But I snapped up The Consul wanting to hear his inside take on Situationism. Since Pegeen had been his wife, the whole Peggy-Pegeen story gets told along the way.

About Rumney and the Guggenheims, Rumney’s friends have anecdotes from when it all started snowballing. Artist Guy Atkins somewhat famously wrote:

“Ralph’s finances seemed always to alternate between penury and almost ridiculous abundance. One day you’d visit him in a squalid room in Neal Street, in a house he shared with people who were more or less tramps; the next you’d meet him in Harry’s Bar in Venice or at the opening of a Max Ernst [Peggy’s husband and Pegeen’s stepfather] exhibition in Paris, on the arm of Pegeen Vail, whom he married soon afterwards. It seemed to me that he accepted poverty with more equanimity than wealth.”

Writer Bernard Kops has an anecdote of seeing Rumney and Peggy together:

“[Ralph] was now popping into and out of our lives with decreasing regularity. And each time he laughingly suffered a sort of metamorphosis: an enormous change in his fortunes…. Apparently, he is betrothed to Pegeen, the daughter of Peggy Guggenheim, one of the richest creatures on this planet… Erica and I are scraping a living by selling books… A taxi pulls up, and Ralph, unusually flustered, jumps out and hurries towards us. ‘Can you loan me a fiver? Quick!’ he begs. ‘What?’ Money is such a rare commodity, and this amount is a week’s survival for us. ‘I’ve got Peggy Guggenheim in the taxi, and I’ve got to pay the cabby.’ ‘But she’s the richest woman in the world.’ ‘I know, but she never carries any cash with her.’ I moan and hand over our day’s takings, our worldly wealth, the last of our cash. We are now skint, but we laugh. What else can you do? Ralph was operating again. A Mephistophelian creature.”

Rumney had met Peggy first. She wanted to buy his painting The Change (currently hanging in the Tate gallery in London). But the sale didn’t work out immediately. Then Ralph met Pegeen – not realizing she was Peggy’s daughter — and successfully pursued her romantically:

“I was hit by the most classic, unexpected form of love at first sight… it was quite obvious that all the men there were trying to pick up Pegeen. I must have been the only one who didn’t know she was Peggy Guggenheim’s daughter. Since she looked fed up, I suggested to her rather abruptly that we get out of there. I took her by the hand, she came back to my place. And that’s how it all started. Some days later her mother, still in pursuit of my painting, returned to the fray. I told her I couldn’t sell it to her as it now belonged to Pegeen. She snarled at her, ‘You’re fucking your way up to quite a collection!’” (The Consul, p. 29)

Coming from Peggy, who had taken much of the art world to bed, the intended insult was hypocritical.

Peggy’s relationship with Ralph never recovered, and she constantly maneuvered to break up her daughter’s relationship with him. According to Rumney, Peggy’s machinations put Pegeen under enormous stress:

“[Peggy] hated everything about me…. She offered me fifty thousand dollars in return for agreeing never to see her daughter again. I told her to go and fuck herself…. I think Peggy did everything she could to destroy our relationship and to have control over her daughter. For Pegeen, the situation was unbearable. I’ve lost count of the number of times I saved her from suicide attempts. She was depressive, or rather, I would say, anguished. Pegeen’s problem, in my opinion, was that she wanted a real relationship with her mother, but her mother was incapable of having human relationships or giving affection.” (pp. 90-91)

Art Addict made largely the same point about Peggy (while still implying Rumney was to blame for Pegeen’s suicide). In a 2017 Vanity Fair article, Rumney’s and Pegeen’s son, Sandro, said of Peggy that “she had a knack for making my mother cry…. She had tormented Pegeen and ostracized Ralph.”

A mutual friend of Rumney’s and Peggy’s, Alan Ansen (of Beat generation fame), hosted a poetry reading that was meant in part to heal the rift between Peggy and Rumney. But it went wrong:

“In his opinion, the evening would offer a good opportunity for a reconciliation between the two of us. When she arrived she was given the best armchair. We would have put her on a throne if we’d had one. Allen Ginsberg began to read ‘Howl’ and other texts. During the reading he became more and more impassioned and was soaked in sweat, exhausted. It was hot, and people were getting increasingly drunk. Allen pulled off his T-shirt and chucked it across the room. Disaster! It landed on Peggy’s head. She made a scene and stormed out, saying Stravinsky would never have behaved like that.” (p. 35)

Rumney, Peggy, and Pegeen all shared addictive behaviors. Peggy alleged Rumney’s alcoholism was The Problem. But all of them had those issues. Pegeen’s addictive personality – and her suicide attempts — predated her relationship with Rumney. Rumney claims he personally prevented her from committing suicide 15 times, and that she had been suicidal for 13 years before they met. I would argue there was even an addictive aspect to the multiple attempts. Rumney essentially blames Peggy, but he doesn’t shy away from the fact that he was also an alcoholic:

“Pegeen’s milieu, her mother and father, were part of that generation of American alcoholics from the 1920s. I would sometimes get pissed, but I wasn’t used to the American martini system, where you got drunk before dinner. I took to it like a fish to gin. In the case of Pegeen, who took barbiturates and tranquilizers, the alcohol-medicine cocktail was toxic. I tried as far as I could to stop her taking one or the other. In theory, she agreed with me, but it caused her painful stress. One day, returning home in Paris, I didn’t find her. In extreme distress, Pegeen had called her mother because… I cut off her supply of tranquilizers…. She was being looked after by Peggy’s doctor, a perfect bastard. He’d put her back on Valium. When I saw this, I really lost my temper with him. You know that with stuff like that it’s very hard to stop once you’re back onto it. And she had practically stopped.” (pp. 89-90)

After running away to her mother’s house and its source of tranquilizers, Pegeen then felt trapped there and would call Rumney to help get her out of Peggy’s control. Pegeen was being pulled apart like taffy between her mother and her husband, along an axis of addiction.

Playing armchair psychiatrist for a moment, I think it’s possible that Peggy suffered from PTSD or a related trauma disorder, possibly from the physical and emotional abuse of her first husband artist Laurence Vail, as she describes in Art Addict. That or a personality disorder might explain her seemingly monstrous ability to withhold affection – a classic tactic of emotional abuse. Whatever the explanation, if there is one, Sandro noted Peggy’s withholding behaviors too. From the Vanity Fair article: “To think that she loved me and considered me her favorite grandchild and it never showed…”

Peggy’s accusations against Rumney – and her bottomless supply of lawyers – made his life extremely difficult in the wake of Pegeen’s suicide. Although there were no grounds for prosecution, Peggy had not only effectively accused him of murder, but she successfully took Sandro away. One of Peggy’s other grandchildren eventually confronted her, and the resulting exchange was reported back to Rumney in a letter: “‘Do you really believe Ralph killed Pegeen?’ ‘Of course not!’”

Rumney said of Pegeen as an artist:

“…I don’t want to give the impression that Pegeen was only a depressive woman or only tormented by her neuroses. She was an artist who lived her art and whose life was art… there’s a high price to pay for such integrity. Her paintings, especially the pastels, are very deceptive if you only look at the surface where, at first glance, there is nothing but light, color, and festivity. It’s only after a deeper contemplation that you perceive the poignant beauty and anguish that her work breathes. Her work reflected her experience.” (p. 90)

When Rumney said Pegeen was “an artist who lived her art and whose life was art,” that is one of the highest compliments a Situationist can give. To live life as art was the Situationist ideal of perfect authenticity and perfect creative freedom. Rumney never stopped living like a Situationist and he admired those qualities in her. He loved her work, produced as it was in the shadow of her mother Peggy Guggenheim, one of the greatest and most damaged people who ever lived. The quality of Pegeen’s work was hard won. The “high price to pay for such integrity” involved her own extinction.

More in my Avant-Garde Women series:

–Eliane Brau, the Invisible Icon

–Michele Bernstein, Queen of the Situationists

–Sophie Taeuber, Founding Dadaist

–The Hundred-Jointed Dancer and the Laban Ladies

–Emmy Hennings, “Shining Star of the Voltaire”

–Review of the Novel “Branded” by Founding Dadaist Emmy Hennings

An index of all Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments