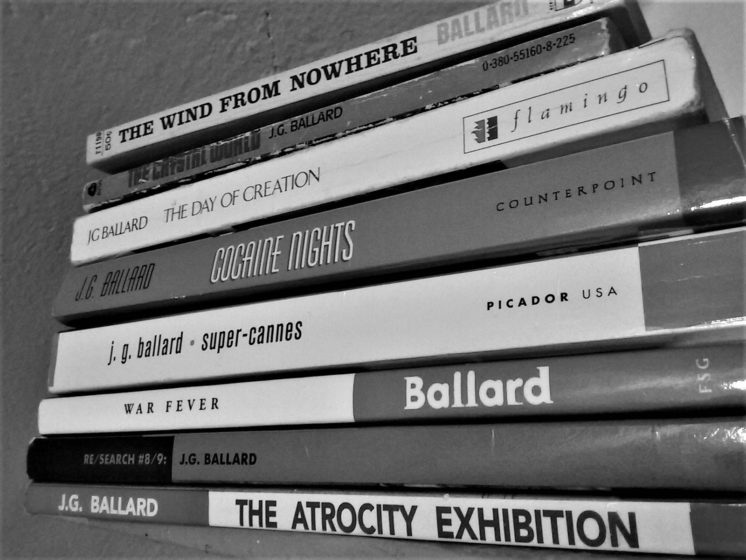

My Favorite Writers/Biggest Influences: J.G. Ballard

J.G. Ballard was born in 1930 to English parents living in Shanghai. He died in London in 2009.

Ballard’s life and career are notable in many ways. As a child in Shanghai, he survived the Japanese invasion of China, and was imprisoned for two years in an internment camp. As a science fiction writer getting started in the early 1960s, he became identified with sci-fi’s “new wave.” This was a generation that turned away from the style epitomized by Isaac Asimov, where stories took place mostly in deep space or the deep future. Ballard felt that science fiction had to speak to the present to be relevant. In his hands, science fiction came back down to earth.

Set in the present or at most in the near-future, Ballard wrote a series of disaster novels to analyze the human psyche. A 2003 BBC profile called him a “tireless pathologist of the modern condition.” In that same piece, Ballard explains his disaster novels thusly: “The English have always written disaster fiction. I think it may be something to do with the climate; it may be something to do with being cooped up in what is a sort of glorified lifeboat moored in the North Sea.”

After the tragic death of his wife Mary in 1964, his writing took an intensely dark and weird turn. Two books written in this period – “The Atrocity Exhibition” and “Crash” — were tried for obscenity, and continue to be controversial. He is considered one of the founders of the genre “transgressive fiction,” where protagonists act in evil or criminal ways; this is much like William S. Burroughs (writer #2 in this series), who Ballard lionized. Towards the end of Ballard’s career, his fiction books took the form of crime novels, but continued a lifelong exploration of how the world threatens to drive us insane, and how we might adapt.

Shanghai

Interviewed in the book Dreammakers (ed. Charles Pratt, Berkeley, 1980), Ballard described the Shanghai of his youth this way:

“Shanghai was a huge, wide-open city full of political gangsters, criminals of every conceivable kind, a melting pot for refugees from Europe, and White Russians, refugees from the Russian revolution – it was a city with absolutely no restraints on anything. Gambling, racketeering, prostitution, and everything that comes from the collusions between the very rich – there were thousands of millionaires – and the very poor – no one was ever poorer than the Shanghai proletariat. On top of that, superimpose World War II.”

The Japanese occupied the city shortly after the outbreak of the war, rounded up all the foreign workers and their families (including the Ballards), and held them in internment camps. Ballard dramatized those experiences in his 1984 semi-autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun, which was turned into a movie directed by Steven Spielberg. The young Ballard was played by a 13-year-old Christian Bale in his first big screen role. (The two other feature films made from Ballard books are the 1996 David Cronenberg film “Crash” starring James Spader, and the 2015 Ben Wheatley film “High-Rise” starring Tom Hiddelston.)

After World War II ended, the family moved back to England and Ballard finished school there. It was a jarring disconnect to go from his Shanghai wartime experiences to England. He dabbled as a writer, but fresh out of high school in 1950, he wanted to become a psychiatrist. In an interview (printed in Foundation no. 24, Feb. 1982) he put it like this: “I became very interested in psychoanalysis while still at school, and read almost all the Freud I could lay my hands on …. England seemed a very strange country. Both the physical landscape and the social and psychological landscapes seemed fit subjects for analysis – extremely constrained and rigid and repressed compared with the sort of background I had. To come from Shanghai, and from the war itself where everything had been shaken to its foundations, to come to England and find this narrow-minded puritanical world – this was the most repressed society I’d ever known!” In an interview on “The South Bank Show” in 2006 he said: “I thought, if I have to become a psychiatrist, my first patient will be me…. had I been a psychiatrist (instead of a controversial writer), I might have been able to do real damage.”

However, after two years of studying medicine towards a psychiatry degree, “I felt I’d completed the interesting phase… I wanted to write – I felt the power of my imagination pushing at the door of my mind and I wanted to open it.”

He began writing stories full-time, publishing them in the science-fiction magazines of the day, and later he blossomed into a novelist.

Surrealist Influence

Ballard’s influences included not only psychoanalysis, but the surrealist painters. In an interview with Re/Search in 1982, Ballard described the appeal of the surrealists this way:

“In the 40s and 50s, I thought that surrealism was the most important imaginative enterprise this century has embarked on. And I still do. For me the paintings of the surrealists have opened windows on the real world, and I don’t mean that as any literary conceit, I mean that literally …. That’s what always attracted me to the surrealists – they had the inner eye. The inner eye remained critical; it didn’t just respond passively to the imagination. That critical eye the surrealists have toward their own fantasies – you feel that all the painters are awake – that these are dreams dreamt by sleepers who are awake.”

Later, in a BBC interview, he said, “They seemed to be painting states of mind – which I was interested in doing also.”

He addressed the topic again in a 1983 Interview with Catherine Bresson: “I am interested in the surrealists altogether, because I am a great believer in the need of imagination to transform everything, otherwise we’ll have to take the world as we find it, and I don’t think we should.”

Death of Mary Ballard

Ballard and his wife Mary got married in 1955 for what Ballard called “ten happy years.” In 1964, when Mary was 34, the couple took a vacation to Alicante, Spain with their three young children, Jim, Fay, and Bea. There Mary caught pneumonia, and within a few days, she unexpectedly died. The three Ballard children were between six and nine years old.

Ballard’s daughter Fay, now an artist, discussed the tragedy in a 2014 interview for an article in The Guardian (“JG Ballard’s daughter on the mother who could never be mentioned,” The Guardian, 6/20/2014):

“She recalls a doctor visiting their holiday apartment and her mother’s fight to breathe with the aid of an oxygen cylinder; and, finally, her father emerging from the bedroom, holding his children tightly and saying, ‘She’s dead.’ …. ‘I remember my mother dying, quite vividly, and afterwards sitting in the car … and I was in the passenger seat and Daddy just cried and cried. After that, we moved forward – that was it …. My father was the most wonderful, loving, brilliant father, but we never talked about our mother. Not once. We couldn’t discuss her with the wider family either. I never discussed her with Bea or Jim. I felt very awkward if her name ever came up. I buried the trauma deep inside of me.’ Did she ever feel angry with him for not being able to talk about her mother? ‘No, I was more … sympathetic. I can understand that as a man left with three children to bring up, you have to make these choices, and it was partly a convention of the time and he felt he had to move on.’”

The Ballard family’s repression of Mary’s death is difficult to reconcile with Ballard’s criticism of England being “the most repressed society I’d ever known.” In the end perhaps there’s not much more to it than this: despite being raised in Shanghai during World War II, Ballard was fully English after all. I admit I can’t fathom it. My father died when I and my siblings were young, and we have never stopped talking about him with our mother. But then again, we are American from emotive stock.

Ballard’s daughter Bea addressed the issue in “Tragedies Marking JG Ballard’s Life,” saying:

“My father had two extreme experiences in his life – his internment as a young child in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, where he saw horrible cruelty, and the terrible tragedy of my mother’s sudden death. He knew how difficult life could be, but he showed courage and gave us a loving, happy and secure environment … he was a brilliant example to me when my husband died and later when I was diagnosed with breast cancer. He was a great survivor, and so am I.”

Ballard raised his three kids alone while being a full-time writer, working from home. He wrote later in his book Miracles of Life (the title refers to his children):

“Some fathers make good mothers and I hope I was one of them, though most of the women who know me would say that I made a very slatternly mother … too often to be found with a cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other — in short, the kind of mother … of whom the social services deeply disapprove.”

Ballard’s Prose

Ballard’s prose is unlike any other. He said somewhere that he admired the writing of Jorge Luis Borges (writer #1 in the series) for its clear, economical style. The two writers are also similar in the way they conflate the inner and the outer world. But Borges does not write as lyrically as Ballard, nor are Borges’ similes and metaphors quite so spectacular.

One seemingly simple Ballard sentence from his novel The Day of Creation (one of the most lyrical books I have ever read) has stuck with me as an exemplar: “The sky was a wall of cobalt.” Until reading that, I had always thought of the sky as a dome – to a certain extent we are all trained to think of it that way. If anything, one might think of the sky as a ceiling, a horizontal cover overhead. Ballard shifts the perspective, making of the sky a vertical thing that confronts a person straight-on – as of course it sometimes does — I just never thought of it that way. A wall of cobalt – spectacular! You can almost feel the perspective shifting in your mind, as the previously dome-shaped, overhead sky turns to face you, exchanging its horizontal axis for a new, vertical one. The metaphor is a magic trick. It is one sentence, the reading of which changes you, effortlessly showing you what’s possible – a different way of seeing. Ballard’s surrealist influences can be seen behind that wall.

With Ballard, perspectives always tilt towards the infinite. In “The Atrocity Exhibition,” he describes feelings between characters with the phrase, “transits of touch and feeling as serene as the transits of a dune.” It’s a mesmerizing take on a mood. The inner space of the mind is mapped on the outer space of the world for a moment, with the time element slowed way down. Feelings seem to stretch into centuries as “the transits of a dune.” It’s a theme of his work, and also his take as a writer: no matter what technology we have, no matter what the global catastrophe we face — the meat of the story takes place in people’s heads. The space-and-time dimension is one axis, and there is a whole other axis of: inside the mind. And the two are hopelessly confused. Those are Ballardian dystopias. (Ballard’s work is so singular that the word “Ballardian” actually exists.)

Another of Ballard’s little tricks that I adore is how he describes light. From this partial list of examples I have taken from his novel “Concrete Island,” you can see that he writes about light as if it had the qualities of a solid, or of an active force instead of an ephemeral quality: bar of light; panel of light; the morning light steepened; sunlight drew away the haze; the air shed its light; the yellow light moved across the grass as if covering the blades with ever-thickening layers of lacquer.

The novel is not science-fiction per se, but his metaphorical shifting of light into a different element lends the book an otherworldly atmosphere. Again, one senses the surrealists at work behind that light.

A final example: in the story “Myths of the Near Future,” Ballard conflates space, time, and light into a single mass. I consider the feat practically an alchemical miracle; I cannot imagine any other writer even thinking of it, not to mention being able to pull it off.

He repeats the trick in another short story, “Memories of the Space Age.” The premise of the story is that space travel has kicked off a sort of conceptual disease where time is slowly stopping. The epicenter of the disease – the “space sickness” — is Cape Kennedy, the center of the American space age. Going to space has destroyed society as people drop out, murmuring mystically about astronauts until lapsing into coma and death. The disease is described like this:

“Could it be that traveling into outer space, even thinking about and watching it on television, was a forced evolutionary step with unforeseen consequences, the eating of a very special kind of forbidden fruit? Perhaps, for the central nervous system, space was not a linear structure at all, but a model for an advanced condition of time, a metaphor for eternity which they were wrong to try and grasp…”

The plot concerns some of the last survivors of the space sickness making their way to Cape Kennedy to solve the mystery before time stops completely. One of them has gone mad and become murderously delusional, another has died, and meanwhile as time slows, “it seems to take all day for a bird to cross the sky.”

Even if that were it, I would think this was an astonishingly original idea for a story – not “hard science fiction” where everything must be explainable in conventional physics terms, but “science fantasy” where conventional physics is bent to the purpose of the story. In fact, the bending of physics is the story.

But what blows my mind every time is his treatment of light. In a normal science fiction tale, if time were to slow to a stop, everything would become a motionless statue, and that would be it. That is the sort of pedestrian time-travel cliché. But Ballard’s central insight, and what enlivens this tale beyond the ordinary, is how light would behave if time slowed down. In keeping with his habit of treating light like a solid, as time slows down, light accumulates on surfaces. It doesn’t have time to bounce off of objects, so objects become brighter and brighter. Objects also become seemingly larger as past and future collect into one space. The story grows more psychedelic as it progresses. Especially, in this touching passage; the character Sheppard finds the desiccated body of his dead wife in what reads as a fantasy memorial to Mary Ballard:

“The light continued to grow brighter, radiating outwards from the gantries of the Space Center, inflaming the trees and flowers and paving the dusty sidewalks with a carpet of diamonds …. Sheppard crossed the chamber, careful not to touch the glowing chairs …. Lying on (a) bare mattress was an elderly woman in a bathrobe … hair hidden inside a white towel wrapped securely around her forehead …. Looking down at the waxy skin of this once familiar face, a part of his life for so many years, Sheppard at first thought that he was looking at the corpse of his mother. But as he pulled back the velvet drape the sunlight touched the porcelain caps of her teeth. ‘Elaine…’ Already he accepted that she was dead, that he had come too late …. (He) touched her forehead. His nervous hand dislodged the towel, exposing her bald scalp. But before he could replace the grey skull-cloth he felt something seize his wrist. Her right hand, a clutch of knobbly sticks from which all feeling had long expired, moved and took his own. Her weak eyes stared calmly at Sheppard, recognizing this young husband without any surprise …. Trying to warm her hand, Sheppard felt an enormous sense of relief, knowing that all the pain and uncertainty of the past months … had been worthwhile. He felt a race of affection for his wife, a need to give way to all the stored emotions he had been unable to express since her death. There were a thousand and one things to tell her … (He felt) confused by the almost funeral glimmer that had begun to emanate from Elaine’s body. But as she stirred and touched her face, a warm light suffused her grey skin. Her face was softening, the bony points of her forehead retreated into the smooth temples, her mouth lost its death grimace and became the bright bow of the young student he had first seen 20 years ago, smiling at him across the tennis club pool. She was a child again, her parched body flushed and irrigated by her previous selves, a lively schoolgirl animated by the images of her past and future. She sat up, strong fingers releasing the death cap around her head, and shook loose the damp tresses of silver hair. She reached her hand towards Sheppard, trying to embrace her husband … Already her arms and shoulders were sheathed in light, that electric plumage which he now wore himself, winged lover of this winged woman …. Sheppard embraced his wife and lifted her from the bed, eager to let this young woman escape into the sunlight.”

Other installments in this series:

All my essay series here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments