My Favorite Writers/Biggest Influences: William S. Burroughs

William S. Burroughs was born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1914. He died in Lawrence, Kansas in 1997.

Wrestling with Burroughs’ Immorality

Burroughs is a deeply problematic and divisive moral figure. He suffered sexual abuse as a child from a caregiver. For long stretches of his life, he associated with criminals and the seediest countercultures of hard drugs. He has written about being a junkie and robbing passed-out drunks for fix money. He lusted for boys ages 12 and up.

He famously shot and killed his wife Joan Vollmer in a drunken “William Tell act” at a party in Mexico City in 1951. He addressed the incident in the introduction to Queer (the book he wrote while awaiting trial), and he basically only says how it affected him personally. I have gotten no sense of Joan Vollmer at all from his writing, and I have looked. The relationship and tragic shooting has been dramatized in at least two films: “Naked Lunch” (Vollmer portrayed by Judy Davis), and “Beat” (Vollmer portrayed by Courtney Love). Both films are under rated. It is only in those highly-fictionalized films that I have gained any slight sense of who Joan Vollmer might have been.

The killing of Vollmer is a particularly ugly fact given that a misogynist streak is evident in some of Burroughs’ early writing. I forget where exactly, I seem to recall from essays written when he was living in London in the 1970s? Anyway, for a while, I was keen on the question of whether he murdered her. And for a time, I was convinced he did it, although I could never find evidence. Allen Ginsberg knew and loved them both, and defended the tragedy as an accident, so if you trust Allen Ginsberg, which I do…

Burroughs was convicted of manslaughter and given a suspended sentence. The sentence was given in absentia because he had already fled the country.

Despite the ugliness of the crime, and all his other crimes, in his later years Burroughs gained prominent fans, defenders, and collaborators who included women in art, music, and literature (including Patti Smith, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Debbie Harry, Ann Charters, Angela Carter, Kathy Acker, Laurie Anderson, and Kim Gordon). Burroughs could work with strong women. He was good enough for Patti Smith to say he was on par with the Pope. I think perhaps he was largely forgiven for the scattered misogynistic passages by these women because they regarded them as aberrances or excesses in the context of his overall literary value. That’s why I personally overlook the stuff, even as it is an obvious stain. But I can’t quit him. I spend a lot of time rationalizing it.

One mitigating fact is that his vilest utterances characterizing women as parasitical on men (for instance) pale in comparison to things he wrote against heterosexual white men, so, that’s a plus I guess? Particularly, patriarchal white men abusing positions of authority. He also denigrated many of his gay characters with outlandish caricatures and stereotypes, even as he himself was gay. Perhaps it stemmed from self-loathing, but there was also always a wink in there it seemed to me, betraying layers of irony still not fully excavated. He seemed to reserve a special hatred for Christianity, but also Islam, and the root of all that lies in a contempt for any mechanism for controlling another person. So he hated governments, societies, and families. His (few) knocks against lesbians almost seem respectful since he knows they don’t need him at all, and he is not sure how to deal insults in that situation of detente. He certainly hated the rich and poor alike because they are all human, and humanity seems to be what he hated most. He hated humanity’s capacity for hate, and in that I see Burroughs’ self-loathing, and his tremendous irony, folding in on itself.

A major source of criticism of Burroughs is his constant use of pederastic imagery, which feels eerily at times like you’re reading the fantasy journal of a pedophile. On the one hand you have the mere fact of Burroughs’ homosexuality, for which he is credited by writer Dennis Cooper as “along with Jean Genet, John Rechy, and Ginsberg, [Burroughs] helped make homosexuality seem cool and highbrow, providing gay liberation with a delicious edge.”

That said, his seemingly endless fascination with underage boys might explain why Burroughs has not been more embraced by gay culture. That and the drugs, and the shooting of his wife, make terrible copy.

Burroughs was not a role model. He was a lifelong pervert who had no respect for the moral or legal basis for a statutory age of consent. He was a moral failure, and a toxic figure. Yet I always thrilled to his acid hatred of racist country sheriffs and evil white church ladies, and his unflinching view of the scope of human depravity.

One group that appears entirely spared from Burroughs’ hatred is African-Americans. He reserved a special hatred for racists and racism. One of the finest chapters in Naked Lunch is “The County Clerk.” This astounding piece consists almost entirely of a vile monologue from an inveterate racist, an American southerner county clerk spewing atrocious sentiments, including against women and gays. The clerk’s own words – written with the finest ear for accent and regional lingo – annihilate bigotry and ignorance. The chapter is a tour de force of American writing, and undeniably argues for a social justice ethos. Perhaps Jack Kerouac was thinking of this chapter when he said Burroughs was the greatest satirist since Jonathan Swift.

Separating the artist from the work is an important problem that we struggle with in many revisions of artists’ reputations, for instance the modern reappraisal of Paul Gaugin in a similar light. Burroughs’ reputation may not be able to survive another generation of scrutiny. The best I can say about him as a person is that he was deeply flawed. These questions do not resolve easily for me as a lifelong fan of his writing. I try not to idolize him. But as a prose stylist, he has been the greatest influence on my own writing without question, from my teen years onward, and I can’t deny that. His unflinching examination of the worst humanity has to offer was conducted in a style that is unmatched by any of my other favorites, despite his moral and criminal failings. I consider him a great moralist, and also a great hypocrite; a damaged mind that wrestled with mental instability and outright madness.

Literary Value

Burroughs’ output may safely be considered the unfiltered rantings of an insane person. No aspect is aspirational per se except the quality of his prose. The good one finds is so exceptional that it cannot be found elsewhere, often hilariously so. Like the restaurant scene and the “purple-assed baboon” routine in the Naked Lunch chapter “Islam Incorporated and the Parties of Interzone.” The section therein called “Manhattan Serenade” must be among the most savage comic passages ever penned by mortal hands. I cannot think of any writer as brutal or as funny: “Paul emerges from retirement in a local nut house and takes over the restaurant to dispense something he calls the ‘Transcendental Cuisine’… Imperceptibly the quality of the food declines until he is serving literal garbage, the clients too intimidated by the reputation of Chez Robert to protest….”

The Naked Lunch chapter “The Examination” is another literary achievement, as a secret-police bureaucrat interrogates a man he suspects of being gay. Its humor comes from the fact that the man is not gay — but by the end, the interrogator has questioned him so expertly, he has made him doubt his own sexuality, and we see the man is doomed. The chapter destroys any simple picture of either/or sexuality, at the same time putting this power in the hands of a homophobic police state figure. It’s as chilling as Kafka.

There is a hallucinatory image in Naked Lunch of a beautiful hetero love scene, like out of a primal mythology: the man’s genitals sprout buds, and the woman’s genitals grow a tuber into the ground and “their bodies disintegrate in green explosions.” It’s bizarre and beautiful. It signals maybe somewhere behind the noise there’s a fractured vision of … what? A wholeness in nature? Is there a unity of the sexes after all? It’s brief but it’s a highlight of the book.

The structure of Naked Lunch is a series of peaks. Every page is explosive, surreal, shocking, wondrous. To me it reads like a reverse-Bible.

Burroughs is recognized as a forerunner of the literary genre of “Transgressive Fiction,” wherein social norms are broken by the protagonists. These authors are not trying to promote evil or crime, but to comment on those things, use them as symbols, weave them into themes, and express things about them. The use of imagery and/or subject matter does not necessarily entail celebration or promotion. It may in fact mean its opposite, through irony and sarcasm. Burroughs’ “protagonists” are often evil and/or insane, in an evil and insane world.

I was first introduced to Burroughs’ work by my childhood friend Jason Bauer, who showed me a documentary when I was a high school junior. (Jason later died trying to kick his own addictions. So Burroughs was undoubtedly a terrible influence on him; for my part, I considered Burroughs’ struggle with addiction as a cautionary tale.)

The documentary didn’t make a huge impression on me. But Jason also introduced me to the performance artist/musician Laurie Anderson. I bought a handful of Laurie Anderson albums and studied them closely, and that is where I really discovered Burroughs: on the album Mister Heartbreak, Burroughs performs vocals on the track “Sharkey’s Night” and it was revelatory. I was like, “Who IS this guy??”

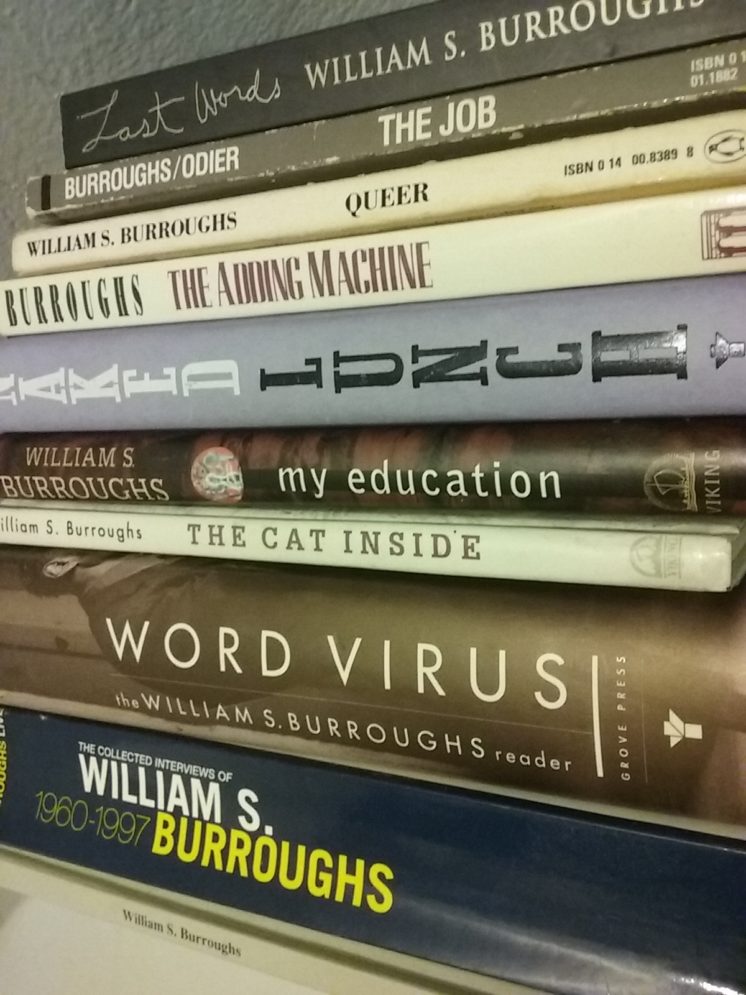

A writer’s written words should be enough to make you “get it,” but sometimes hearing a writer’s voice adds a whole other dimension of appreciation. This has happened to me particularly in reference to the three gods of the Beat generation: Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. Recordings of them reading their own works helped bring their writing alive. In Burroughs’ case, I had not even read his stuff yet, but hearing that unique voice electrified me. I bought two books of his right off the bat, devouring them. I didn’t realize it, but I had purchased the first two books he had ever written: Junky, and Queer.

They are perhaps unusual first books of his to read in that they are atypical; he was still trying to write linear narratives. They are autobiographical instead of the hallucinatory postmodernism of his later years. But what comes through is his precision and economy of language, and his details. His writer’s eye was seemingly sprung from genius, as Norman Mailer famously noted.

The first one I read was Queer, a story of unrequited love. It is utterly heartbreaking. Burroughs is an iconic figure of human alienation; I believe it was one of his biographers who wrote that he “suffered from a sense of alienation so great as to constitute extraterrestrial status.” That insight has functioned as my skeleton key to unlock his coldness, his bitterness, his condemnations. Abused as a child, he grew up broken, found himself on the outside of love, and condemned humanity for it. In Queer, he displays that vulnerability, and it aches with loneliness and desperation. It is the most human work of this otherwise inhuman writer. He wouldn’t publish it until later in his life, when he felt less vulnerable to the depths of feeling that are recorded there.

Another often-tender book, written towards the end of his career, is The Cat Inside. It is an old man’s meditations on his cats and their importance to him. Burroughs was admittedly cruel to cats as a younger man, but he grew into a tenderness for them that is softly evinced in this book.

His late “Western Lands” trilogy is notable for threading the needle between readable narrative and postmodern experiment. By and large they have conventional novel structures (apparently at the insistence of his publisher). But there are hallucinatory bits sprinkled throughout for that edge. These books are good starting points for new readers; I read them out of order so that is not important; they are accessible and fun. They are best described as gay science-fiction Westerns, and well, that’s what they are.

But for my money, his most famous book Naked Lunch is his best. I will not quibble, I think it contains some of the finest writing I have ever read, as I have stated above. I return to it again and again. Burroughs as a man was an evil human failure. And Naked Lunch contains evil, without question. It is difficult reading at times. The chapters may be read in any order and they do not weave a larger narrative, but instead they show you the human condition in a series of visionary passages. Although many chapters function as tight short stories, other chapters are non-linear — writing at the level of the paragraph, or, even more atomized, at the level of the sentence.

Most of his work contains brief experimental passages that are hard to read, and they may be skipped without much hesitation. A couple of his books however are entirely gibberish: The Soft Machine and The Ticket that Exploded. Like James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, they are essentially unreadable. (Okay I read them.)

What Burroughs’ difficult passages lack in readability, they make up for in images and word choices that are fascinating and beguiling. For Naked Lunch alone, I consider him as great as the other great Williams: William Blake, and William Shakespeare. I am ashamed to say that, but it is no mere hyperbole. Any fans of language owe it to themselves to dip into Naked Lunch and its pyrotechnic wonders. It is a peerless work of Americana with a global reach, a recording of the decline of 20th Century Earth by one of its worst citizens.

Other installments in this series:

Jorge Luis Borges here.

J.G. Ballard here.

Stanislaw Lem here.

Italo Calvino here.

All my essay series here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

3 Comments

David Beard

about 5 years agoVerushka Kowalski

about 3 years agoJim Richardson (aka Lake Superior Aquaman)

about 3 years ago