Thoughts on Anchorage: Community makes self-reliance possible

In the late 1990s, before it reorganized in bankruptcy, Sun Country Airlines flew out of the Humphrey Terminal at Minneapolis/St. Paul. It ran specials on undersold planes, and I received an email alert, I think, about round-trip tickets to Alaska for $300. It seemed so far away for so little money. I was a graduate student in the College of Agriculture on the Twin Cities campus; I was making $12,000 a year. This was cheap, it was an extravagance, an adventure, a story to tell.

In the late 1990s, before it reorganized in bankruptcy, Sun Country Airlines flew out of the Humphrey Terminal at Minneapolis/St. Paul. It ran specials on undersold planes, and I received an email alert, I think, about round-trip tickets to Alaska for $300. It seemed so far away for so little money. I was a graduate student in the College of Agriculture on the Twin Cities campus; I was making $12,000 a year. This was cheap, it was an extravagance, an adventure, a story to tell.

I boarded the plane in Bloomington and disembarked in Anchorage. (It was the first time I had been to an airport with signage instructing passengers how to check and reclaim your gun.) The bus took me downtown, and I looked for a hotel. In the years before travel websites and mobile phones, this was hard — I had to walk toward hotel signs and hope for vacancies. There were few; the flight was cheap, but the hotels were booked; I spent twice what I spent on my ticket on my hotel, at what felt like a dive for the price.

I was young and weighed less than half what I weigh now, so I started walking. I walked to Cook’s Inlet, which was muddy. “Captain Cook” was not a real person to me, and so his inlet meant little. So, too, did Mt. McKinley mean little to me — Mt. McKinley, also called Dinale or Denali or Bolshaya Gora/Большая Гора, Densmore’s Mountain. The history of its naming means more to me than the mountain. I was more interested in a business dedicated solely to pull tabs.

My first night in Anchorage was barely night; there were 19 hours of daylight — the blackout curtains in my hotel were necessary because it was light until nearly 2 a.m. Everything seemed to stay open later, too. Why close at 10 when there were four hours of daylight still, and tourists aplenty? I visited museums with Indian, Native, Aboriginal art and artifacts — I was still learning the nuances to those words.

The second day, I walked to the antique shops. I believe you can tell a community by its antique shops, and Alaskan shops in the 1990s were filled with the tools of pioneer life (lanterns, etc.) and guns, so many guns.

The second afternoon, I wanted to get as far from the city as I could, so I hopped the bus that drove farthest from town and rode it to the end of the line. That wasn’t very far.

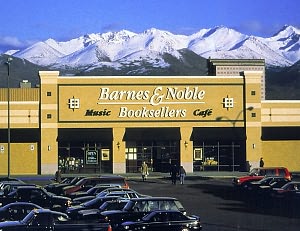

On the way back from the end of the line, I stopped at a Barnes and Noble.

It was the first time I imagined what it would be like to live totally surrounded by water on one side and mountains on the other. I have never lived in the shadow of mountains; in Anchorage, the mountains were horizon and barrier. Alaska is not sewn together by roads, but by flight paths and by boats running the coasts, running around or over or through the mountains.

To “graduate student me,” Barnes and Noble was civilization, but downtown was a reminder of the precarity of that civilization. Historical plaques and photos were scattered downtown commemorating the 1964 Good Friday earthquake. I see the photos of last week’s earthquake and I remember the earthquake of fifty years ago.

From Wikimedia/US Military

A vehicle lies stranded on a collapsed roadway near the airport after an earthquake in Anchorage, Alaska, U.S. November 30, 2018. Nathaniel Wilder | Reuters From CNBC: ‘Alaska Gov. Walker issues disaster declaration after major earthquake damages infrastructure near Anchorage’

California wildfires dominated my newsfeed for weeks. The 2018 Anchorage earthquake is already forgotten, because a former President’s death took over the front page, because the media is like that, and because Alaskans are resilient.

Most of what I think I know about Alaska comes from a single trip to Anchorage and from a deep love for Northern Exposure — which means I know nothing, to be sure. I love Alaska the way I love mincemeat pie — based on a memory of long ago, without any real knowledge of what it really is. (I don’t think my grandma put beef in mincemeat, but maybe it was always there.)

From CBS

Here is the dark secret of my time in Minnesota, since 1995: When I don’t think about it, Minnesota reminds me of Alaska. Bear and moose wander the city. Duluth feels as small a town as Cicely, sometimes. Like Alaskans, Minnesotans, especially Greater Minnesotans, have a disproportionate sense of self-reliance (justified by a sense of remoteness). That self-reliance is ideology as much or more than fact.

Last week I read about 35 rugged outdoorsmen who needed to be rescued from ice on Superior Bay. Blizzards are no longer fatal catastrophes because a complicated web of governmental agencies warn us when the temperature is going to drop sixty degrees overnight, as they did in the Armistice Day blizzard. Duluth and the Lake Superior region of Wisconsin are poised for disaster relief after two years of October storms, funding both Lakewalk reconstruction and access to communities of a few dozen along isolated Wisconsin roads. Our self-reliance needs an asterisk.

Community makes self-reliance possible, whether you are a fisherman on an ice floe or a miner on the range or an Alaskan surviving an earthquake. I hope our community, our national community, gives those rugged, resilient Alaskans all that they need.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

1 Comment

Eric Chandler

about 6 years ago