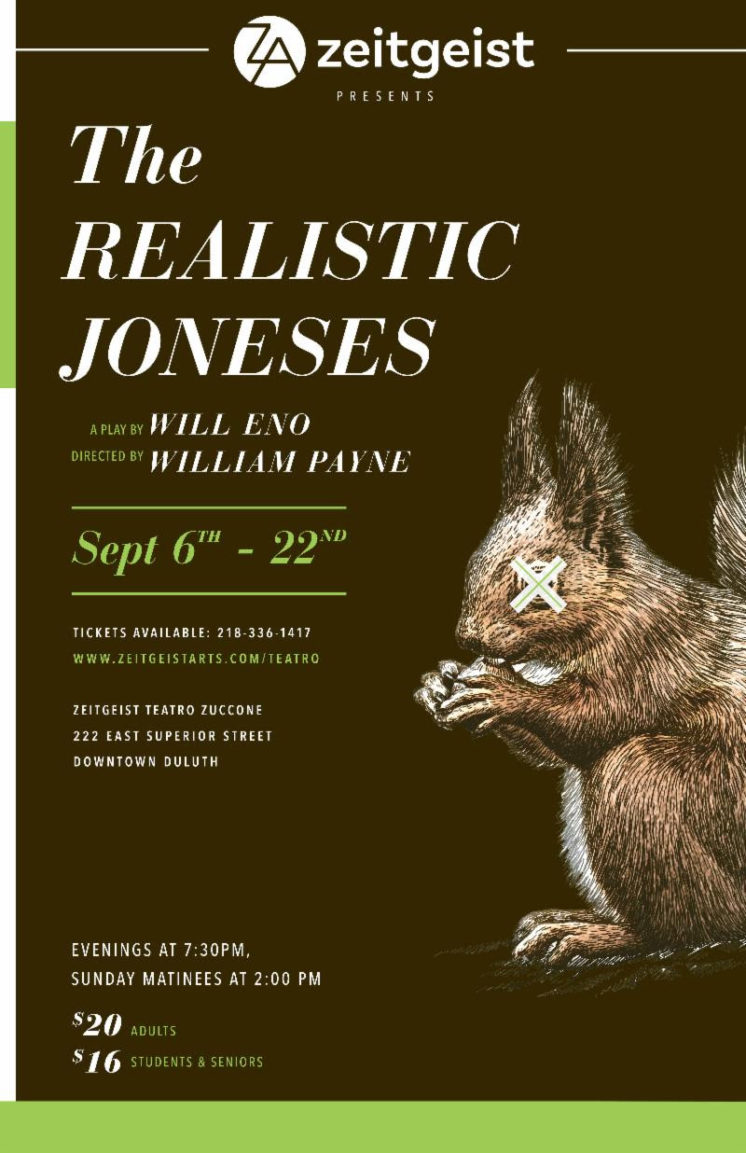

The Realistic Joneses

I left Panera for the Realistic Joneses at the Zeitgeist while, it seemed to me, a woman was in a tree. I’m not entirely sure about the tree part — I know she was in the woods, alongside the creek behind the parking lot separating the Panera from the Aldi complex, and I know that the police and EMTs were looking upward as one of the pines was shaking. I didn’t see her. I could only hear her voice, sadly crying that people believed that something was wrong with her. I felt a sadness that mirrored hers. There was no way for this story to end which didn’t fulfill her words. I wished there were a way for people to just turn their backs and let her leave, if that would be what she wanted.

The retail staff from adjacent stores stood in the parking lot, as did several customers, waiting for something to happen. I mention this because one of my companions at the Realistic Jones noted that she spent most of the play “waiting for something to happen,” until she realized, I think, that nothing more significant will happen than four people living their lives.

At a moment in the intermission, I turned to the director to say: I feel like I’m watching real people.

The play follows a set of couples, both named Jones, living in a small coastal town because it is close to a specialist in a neurological disease.

- In one couple, Bob denies the disease to himself — he will undergo treatments, but he does not want to understand the disease, or its interactions with the meds, or his prognosis. His wife Jennifer shoulders the responsibility to understand those things.

- In the other couple, the husband, John, shoulders the knowledge of the disease alone — his wife, Pony, seems unwilling or unable to learn of her partner’s frailty.

In this way, the play sets up powerfully resonant dynamics. I remembered being a younger man, incapable of managing depression on my own, and incapable of asking for help, just like John. I remembered my mother’s unwillingness to see her prognosis for cancer. (She has survived and is happily still with us.) I remembered a woman who wore a “brave face” while her husband slowly died from a rejected bone marrow transplant. The spectrum of ways that people deal with (or refuse to deal with) physical frailty and emotional trauma are visible in the first act of this play.

Eno’s play, in Payne’s hands has been enacted by a troop capable of making me laugh while hinting at a complicated inner life, aching to be shared.

If I were to complain, and I do so barely, the second act feels rushed — a fault of the script, not the performance. The first act so carefully sets up four individuals and the emotional roadblocks they face. In the second, Bob and John hurriedly learn that they can trust their partners, Pony hurriedly learns that she can be emotionally present for someone else in a moment of vulnerability, and Jennifer learns that if she dopes up her husband, he becomes bearable company. There is a rush to closure, with a more complete narrative and psychological arc, I think, for the male characters than the female.

The quality of the performances is all that sells this closure; the script does them no favors. It worked, last night. I think the magic will hold if you manage to see the show before it closes.

FoxNews interviewed the director and one of the stars here. Bill Payne was also profiled here, in the Human Fabric of Duluth page. The story includes these anecdotes about his mother, which may help you see how this production is an act of generosity.

My dad was a disabled veteran and my mom a homemaker until she got all her kids in school, then she went to college too, to become a teacher. One thing she made sure we did was to go once a year to the Cleveland Museum of Art, once a year to the Cleveland Orchestra, and once a year to the Cleveland Playhouse. It was an ordeal because she didn’t drive. She had six kids she had to get on public transportation to get across town, as we lived on the west side and all the culture was on the east side; but she made sure we got there. That established for me the value of art and I was totally taken with the theater.

[My mom] always played theater soundtracks with all kinds of music but those trips across town to experience that art made all the difference in the world. The thing I try to tell folks is that I have an imagination and it works 24/7, it’s always on. I’ve been this way ever since I was a kid and my mother made it ok. If I felt like putting on a circus she would say ok and I would put on that circus in the backyard. She had an ability to embrace who her kid was. I don’t have artist children but I embraced who they were. One is a scientist and one a soldier and scout and I made sure I helped them find their way. I’m really glad my mother did that for me. -William E. Payne

Payne and his players have been generous to us in this way, too. I’m grateful for a chance to see the play.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments