Schwinning and Losing

When I was a kid I had a blue Schwinn Sting-Ray Fastback 5-speed banana-seat bicycle with ape-hanger handlebars. It was classic and beautiful. I hated it.

When I was a kid I had a blue Schwinn Sting-Ray Fastback 5-speed banana-seat bicycle with ape-hanger handlebars. It was classic and beautiful. I hated it.

That bike was a relic handed down from my significantly older brother, Scott, who bought it in the late 1960s with his paper route money and used it to expedite his collections process. I took it over just as the 1970s turned into the 1980s, and by then banana bikes weren’t cool. Freestyle bikes were the new rage.

In West Duluth at the time we called freestyle bikes “dirt bikes,” a term that would get them confused with motorized dirt bikes in other neighborhoods or other periods in history, but there was no confusion among us. The Huffy BMX is a popular dirt bike I remember, along with Diamondbacks. I wasn’t really tuned into what all the hot brands were, nor was I much of an enthusiast for stunt biking, I just knew I wanted one of those bikes so I could blend in and not look ridiculous when it was time to jump over stuff and race through mud or whatever. But I didn’t want it bad enough to get a paper route and pay for it, I just wanted fate to hand me one. Because if fate hands you anything in this life, it immediately entitles you to think it will hand you things over and over again.

I’m sure there were a lot of kids in my neighborhood who didn’t have a bike at all, and there were certainly a few with bikes as dorky as mine, but at the time it seemed like everyone I hung out with had a cool dirt bike and I had a nerdmobile. It’s hard to really know in retrospect, but I think more than I wanted a dirt bike, I wanted the other kids to not have them so we could all play baseball or tin-can alley instead of failing at stupid bike tricks.

Anyway, when I look back on it, part of me is ashamed for not respecting the good qualities of the bike I was given, but part of me also understands that while the Schwinn was perfectly good for cruising to Eighth Street Market to pick up freezies and other sugar treats, it really wasn’t designed to do what the other kids’ bikes were designed to do. That meant it was less fun, which meant I was less fun, which meant I was a horribly disadvantaged failure at early 1980s life.

Paul Lundgren and his Schwinn Sting-Ray on the left; Brad Maki and his Huffy Bandit on the right, circa 1981.

The inadequacy probably radiated off me and made me an easy target for anyone looking to take advantage of my vanity, either through simple insults or deeply nefarious plots. The snotty comments did indeed get hurled at me periodically, but that was going to happen for any number of reasons at that age or any age. It’s what people do. But the conniving scheme I eventually fell into surprises me to this day. I don’t know if the perpetrator engaged in any research or just happened to hear about me from some other kid. I might have just randomly fallen into his path and he improvised his scheme on the fly, because that’s what it seemed like.

He was an older kid I’d never seen before, and I don’t think I ever saw him again. I would guess I was maybe 10 years old and he was 14 — something like that. He must have lived about two miles away, which to a kid is about the equivalent of 200 standard adult miles. One day he came walking down West Eighth Street in front of my house and saw me on my Schwinn.

Parts of this story are very fuzzy to me, having been so long ago. I think the kid just stopped and started talking to me about my bike, which would be something that had never happened before in any positive way. He thought the Schwinn banana bike was cool. I can’t remember if he said he wanted it for himself or if he knew someone who was into classic bikes or what exactly his pitch was, but he offered to trade me his dirt bike for my Schwinn. I didn’t have to think long about the offer.

He was eager to do the trade right away, but the trick was that his dirt bike was parked at his house, which was two miles away up Highland Street — a steep climb for a little kid on a banana bike. But since he was on foot, we’d walk together and I’d push my bike.

It took a while, but eventually we made it up Highland and turned at either Skyline Parkway or VInland Street. It wasn’t much farther before we got to a house with a big lawn and a dirt bike parked in plain view. This is the point where I should have realized I was being hornswoggled.

The kid told me he was really running late to something, so he was just going to take off on the Schwinn. All I had to do was go and get my new dirt bike, which was in the grass about 100 feet away. I wondered if something was wrong with the bike, but at this point we’d come so far, and it was right there. It looked good. What could be wrong with it that couldn’t be fixed? Even if there was a problem, I knew where the kid lived and could get my old bike back, right?

So I let him ride away with the Schwinn.

I walked down into the yard toward the dirt bike, set it upright and clutched the handlebars, observed that it looked good, and prepared to push it out of the yard to the street. The ride home was going to be fun — all downhill!

I was probably thinking about how I should make sure the brakes work before barrelling down Highland. Or maybe I was just generally checking the bike out or basking in its glory. As soon as I started pushing it away a loud voice came from inside the house.

“Where are you going with that bike?”

I don’t remember if I said something right away or just stood there in shock, not expecting this twist in the plot. Eventually I tried to explain to a silhouette in a window that I had traded my Schwinn for the dirt bike. And then things started happening quickly.

A man came out the door. He was probably in his 40s, but could have been younger or older. I had barely told him anything about the situation, but in less than a minute he informed me that the dirt bike belonged to his son, and some other kid had tricked me into stealing it. He told me to get into his truck and we would chase down the kid who deceived me. The man was going to help me get my bike back.

Telling the story, I cringe the most at this part, because it’s where everything is supposed to go even more horribly wrong than it already has. I knew I shouldn’t get into a truck with some man I didn’t know. But I did it. That kid had my bike. There was no time to think.

Don’t worry, it wasn’t an elaborate abduction plot. Everything the guy said was real. We drove off and spotted the thief riding my Schwinn along Stebner Road as fast as he could. Or maybe it was Vinland Street. I don’t remember anymore. But I remember the man pulling the truck up next to him, yelling at him by name, and the kid jumping off my bike and running off into the woods.

I got my bike back. I immediately forgot the name of the thief after the man yelled it out. I didn’t care about that. I left and never told anyone what happened. It was too embarrassing. I was too stupid. I didn’t deserve to get my bike back. None of this would have happened if I had respected that Schwinn in the first place, but as soon as I had no bike at all I was crushed about losing what I had. Then when I reclaimed my Schwinn and mounted that banana seat, all I wanted was to get home fast and forget all this had happened. But I never did forget.

I don’t think I ever saw that kid or that man again, but of course I probably did. The kid is my insurance salesman now and I don’t even know it. Or he jogs past me every day when I walk my dog or something. Maybe we became friends years later and didn’t recognize each other anymore. Maybe he’s more embarrassed than I am about what happened. Or maybe he’s in prison.

Maybe I sat down at the Gopher Lounge for a beer a few months ago and the hero guy who saved my bike sat next to me. He might be about 75 years old now. We talked for a second about the Bulldogs winning the hockey game on TV or whatever and that was that. There’s no way we’d ever put together that we met for a few minutes in the summer of roughly 1981.

I never did get one of those dirt bikes. Somehow I had a fulfilling adolescence without one. I occasionally wonder if I really learned a lesson that day or not. I still catch myself wanting things I don’t deserve or need just about every day, pondering what level of sacrifice I’d make to obtain them. Maybe I come to my senses quicker because I almost lost that Schwinn.

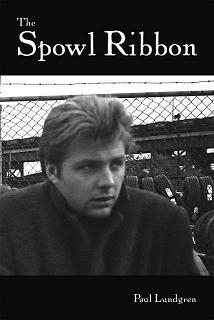

Paul Lundgren is author of The Spowl Ribbon, a book released in 2010 that finally broke even in 2015. Publishing success!

Paul Lundgren is author of The Spowl Ribbon, a book released in 2010 that finally broke even in 2015. Publishing success!

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

1 Comment

Mike Creger

about 7 years ago