Bad Student

‘Cause I survived the ’80s one time already

And I don’t recall it all that fondly

— Craig Finn

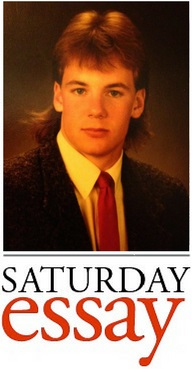

The bemulleted boy in that senior portrait over there came very close to not graduating with his Rochester John Marshall high school class of 1989 mates. One semester more and the rage that had fueled his self-destructive approach to school since 1983 would have elicited an anticlimactic letter explaining why he couldn’t walk in the ceremony and what he’d have to do if he wanted a diploma.

His K-6 career had suggested potential. Then a few months into seventh grade his interest in caring or trying seemed to evaporate. He embodied adolescent apathy. He also transcended it in ways that made very little sense to himself or anyone else. One example: he so bitterly resented being placed into advanced science and English classes (for reasons he could articulate no further than, “I just want to be in the normal classes”), that he intentionally got crummy grades on assignments until people who made such decisions had no choice but to bust him down to non-advanced sections.

At least that’s how I think I remember it. I know he was pissed — furious — about school in general, and still pretty far away from having vocabulary or perspective required to process what he was feeling or why. I know he self-sabotaged, sometimes so willingly it seemed wanton, and sometimes while watching it happen and wishing he knew how to stop it. In those situations, the latter often presented as the former. I also know it’s possible he got kicked out of those advanced sections because he just wasn’t equipped to stay in them. It’s not taking shots at him to say he might just not have been smart enough in ways the classes required students to be.

By his ninth-grade year teachers assumed him to be a “bad student.” By the time that portrait up there was snapped, in early autumn 1988, teachers had so often told him exactly how bad of a student he was, and what a problem that was for them and him, that it’s still sometimes tough for me to see myself in terms other than the ones those teachers used and implied. Does that make sense? Do you understand that as a 46-year-old man I sometimes feel deficient partially because of what adults who were younger than I am now, and who were convinced they were doing the right thing, said to boy me when he was a deeply struggling teenager?

I have a doctorate of education in teaching and learning now. I’ve been a teacher for 20 years and I’m good at it. I vigorously disagree with the premises underlying the label “bad student” and how those teachers applied it to that boy then and how teachers now apply it to struggling kids now. But some labels stick tenaciously enough to withstand life experience that should maybe have torn them off or gradually eroded them.

Kid me disrupted class occasionally in junior high. He got low semester grades throughout junior high and high school — had points deducted for tardiness, late work, missing work, work that looked lazy, and work that showed he truly hadn’t learned what the assignment required him to learn and demonstrate knowing. He came across as fairly blasé about all that stuff and got snotty about being asked to explain himself. So teachers perceived that struggling kid as problematic and let him know it. They told him he was a problem.

Listen: I’m not saying they were “bad teachers.” They were busy and he just seemed pleasantly clueless at best and incorrigibly insolent at worst. Like Mike Seaver from Growing Pains, only much less charming, cute, or well-dressed. I can understand how everything about the kid suggested he was just an entitled wiseass jock who couldn’t be bothered to try. Other kids actually cared or had legitimate problems and required a lot more attention a lot more intensely. Even if some gritty, hip teacher had wanted to make a project out of cracking his dudebro exterior and get him to show how much he really wanted to try, there was just no time for anyone to be his very own personal Michelle Pfeifer from Dangerous Minds. I get it.

And I doubt every kid who gets chastised for struggling grows up to experience long-term effects like the ones I’m obviously trying to work through. I might be a unique case. Maybe I’m just pathetically fragile and ill-equipped to deal with the cold, cruel realities of life. I promise I’m narcissistic and convinced of my own super-specialness, and way more covetous of acknowledgment for just being me than any emotionally or socially healthy person ought to be. I know I spend too much time looking backward in unskillful attempts to figure out what I’m experiencing now.

I’m not asking anyone to feel some sort of way for me because I can’t get over teachers making it very clear how disappointed they were in that boy 30 years ago. I should get over it. I’m working on that. But if you do feel a twinge of something like sympathy for what that kid experienced in the mid-1980s, or if you’re an adult and you know your own version of being dismissed by teachers who equated noncompliant with “bad,” maybe it would be wise to ponder the ways in which present-day adults talk to (and about) kids. And maybe, if you feel bad about what happened to a boy who presented as that one did and lived in a solid home and had nearly every advantage a kid could have in a culture and community maintained to benefit him regardless of how it affects people unlike him . . . maaaybe it would make sense to consider how school life might occasionally feel for kids who actually do follow rules, and who do bust their asses to do everything right, who conform at their own expense and aren’t caught up in self-indulgent emotional angst, and who still can’t get teachers to take them seriously as fellow human beings.

Here’s some of what teachers and counselors asked that boy throughout junior high and high school: “Why don’t you just do what you’re supposed to do? Why do you make things so difficult for yourself? Why don’t you care? Do you want to fail? Do you know how disappointing this work is? Is this how you want people to think about you? You’re smart, Chris — why don’t you act like it? ”

Here’s what teachers never asked him and I struggle to believe they ever wondered about: “Are you terrified? Are you confused? Are you struggling? Are you questioning where you belong, maybe in a way that exceeds what’s typical for people your age? Do you feel like everyone around you gets it and you’re missing something fundamental but you can’t really say that so you just try to make jokes and escape into music and Sports Illustrated and Rolling Stone and pretty much any book you can get your hands on? Do you want to feel and be different but have no idea how to? Are you more frustrated with yourself than your football-dudebro presentation suggests? Do you perform apathy because you feel like you might vaporize or combust without its protection?”

I doubt I’d have known how to answer any of those questions. Whatever I managed other than a mumbled, “I dunno” would have sounded like gibberish comprised of equal parts meatheadedness and trying to sound deep. But having a teacher ask questions like that, whether I could answer them or not, would have mattered.

I can tell you exactly what it felt like the first time a teacher seemed to acknowledge me as a fellow human being in the struggle to find meaning instead of as a “student” — as a subordinate whose overall value and right to be treated and thought about respectfully depends on how willingly and successfully and convincingly it submits. Before News Writing and Reporting II started one night in UMD Humanities 464, Larry Oakes handed me a small, clothbound copy of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge. “Godsey,” he said, “this is a book about a young man who’s searching for something. You seem like you’re searching. Please be careful with it. It was my dad’s. It was published during World War II, when books made like this were rare because of rationing. Take your time with it but please return it.”

I’m not sure I’ve ever thought deeply about that gesture without feeling moved by it as significantly as I was in the original moment. I was a bonehead at 21. I also knew what it meant to be seen instead of problematized. I’ve seldom talked about it out loud without having to pause and compose myself.

As far as I know, Larry treated all students like this: When our stories sucked he told us they sucked and showed us why. He told us when our work was wrong or inappropriate or flat-out stupid. When our stories impressed him he told us that, too. He was never coy about being an award-winning Minneapolis Star Tribune reporter. He also never seemed interested in using his status and expertise as justification for dominating us, making us feel small, or feeling entitled to our deference and adoration. In everything he did as a teacher, he treated us as fellow human beings who were trying to learn difficult things he had known for a while but remembered being difficult to learn. He always asked and expected us to work uncomfortably hard. He never treated us as if our job was to avoid disappointing him.

I’m probably hyperbolizing the boy’s junior-high and high-school experiences a bit. Independent School District 535 wasn’t some sort of “Another Brick in the Wall” situation during the 1980s. Teachers were nice to him. They mostly presented as warm and welcoming. They weren’t awful human beings. Some were probably more empathetic and perceptive than he knew or I remember. I assume most of them cared about helping kids learn and were trying to do that difficult work as mindfully as possible. Teachers get misperceived and mischaracterized in unfair and dehumanizing ways just as often as students do.

Experience and perspective tell me those teachers also, like most teachers I’ve known (including myself), had no idea how condescending and controlling they often were toward kids trying to survive and make sense of confounding situations. Adults’ entitled minimization of children’s (and each other’s) interior lives can be breathtaking in its dearth of empathy. Dismissive chastisement with a smile can feel unspeakably cruel.

And blah blah blah, by mid-spring 1989 there were valid concerns about whether the boy’s semester GPA would be high enough for him to graduate. It was 1.7, but somehow he did. I’m not convinced he should have. He was accepted into UMD on probationary terms — was on probation before even registering for a class — and wound up being a bad student there, too.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

2 Comments

Helmut Flaag

about 7 years agoEndion

about 7 years ago