Duluth Smells Ocean Breezes

Below is the complete text of a Duluth story from page six of The Observer out of Saline, Mich., from Thursday, June 14, 1934, reprinted from Collier’s magazine.

First, it should be noted that tales of Duluth’s shipping canal being hand dug by citizens have been debunked over the years, as described in detail in Tony Dierckins’ book Crossing the Canal: An Illustrated History of Duluth’s Aerial Bridge.

As Dierckins notes on Zenith City Online, “The truth involved more lawyers than shovels. There were no heroic feats by man nor machine, and Wisconsin’s seven-year effort to close the canal never once stopped dredging and improvements. But the legends make much more fun stories, and they also display another aspect of the city’s lore: the work ethic and determined self-sufficiency of Duluth’s pioneers.”

Duluth Smells Ocean Breezes

The time is near, so Duluth believes, when the winds blowing off Lake Superior will carry with them the fragrance of cinnamon and patchouli. The wharves in St. Louis Bay will teem with the color and romance of far places, and a seaport at the head of America’s inland seas will be available to half our population and almost half our wealth. Duluth sees herself as one of the greatest cities of the future. The near future, she hopes. A dream that has glowed for half a century in the face of successive disappointments can’t be darkened by the delays of Congress. Duluth believes in the Seaway: this is the substance of her vision.

By W. B. Courtney

(Reprinted from “Collier’s” by permission.)

Bad news came to Duluth one evening in April of the memorable year 1871. It was carried, thinly and sluggishly, over a single thread of newly strung telegraph wire. Again, on a night in March of this even more memorable year 1934 had news came to Duluth. It was flashed over a hundred humming wires; told in headlines; announced from ten thousand radios to the chagrined Duluthians at their dinner tables in the lovely “Peony City,” at the head of the lakes.

Bad news came to Duluth one evening in April of the memorable year 1871. It was carried, thinly and sluggishly, over a single thread of newly strung telegraph wire. Again, on a night in March of this even more memorable year 1934 had news came to Duluth. It was flashed over a hundred humming wires; told in headlines; announced from ten thousand radios to the chagrined Duluthians at their dinner tables in the lovely “Peony City,” at the head of the lakes.

Seaway Sam talked with me about both occasions. Not that he had personal experience with the first for he is just past middle life, whereas that happened well over half a century ago. But Sam is a sort of repository for all the bad news that ever came to Duluth; the historian of its adversities. Seaway Sam does not mind a bit of philosophizing in the right place, so long as you do not give it the wrong emphasis; do not use it for a crutch, that is. He has no patience with a man (or a town) who uses philosophy for a crutch; who cannot stand chin up to bad news. Boy and man, he has been hearing bad news these many years. “Bad news,” he told me “is bad news, and I won’t deny it. But if you get it often enough; you grow used to it. If you get it oftener, your dander begins to steam. And if you get it oftenest, why you must just pitch in and dig!”

When you look into Seaway Sam’s eyes, filled to the lashes with fiery dreams, you are certain that if will power were a pickaxe, and souls had muscles, he could dig a channel unaided from Duluth to Denmark. And it seems to me that in this doggedness, this spirit of pertinacious hope, he is a child of the city’s traditions and typical of its average burghers, past and present: as witness that black Friday night back in 1871, when Duluth was but a brash new speck on the tip of the finger that Lake Superior pokes into the midriff of the North American continent. It was the runt and the lastborn of the civic twins of the Central North wilderness.

A Civic Superiority Complex.

Superior, the elder village, bullied her from the Wisconsin shore, just across St. Louis bay. Superior was larger, sturdier, faster-growing; in its relation to Duluth it was everything that its name unwittingly implied. And now Superior was relishing an extra chortle, assured that the upstart neighbor had been pushed back on her shabby heels once and for all. Indeed, reliable family memorabilia tell, how a score of the less elegant citizens of Superior went down to Wisconsin Point, as darkness fell, and thumbed their noses and yelled homespun suggestions at some Duluth fishermen on Minnesota Point, across the natural strait through which the St. Louis river flows into the lake.

This was the apt scene for victorious catcalls because in it abided the reason for the controversy.

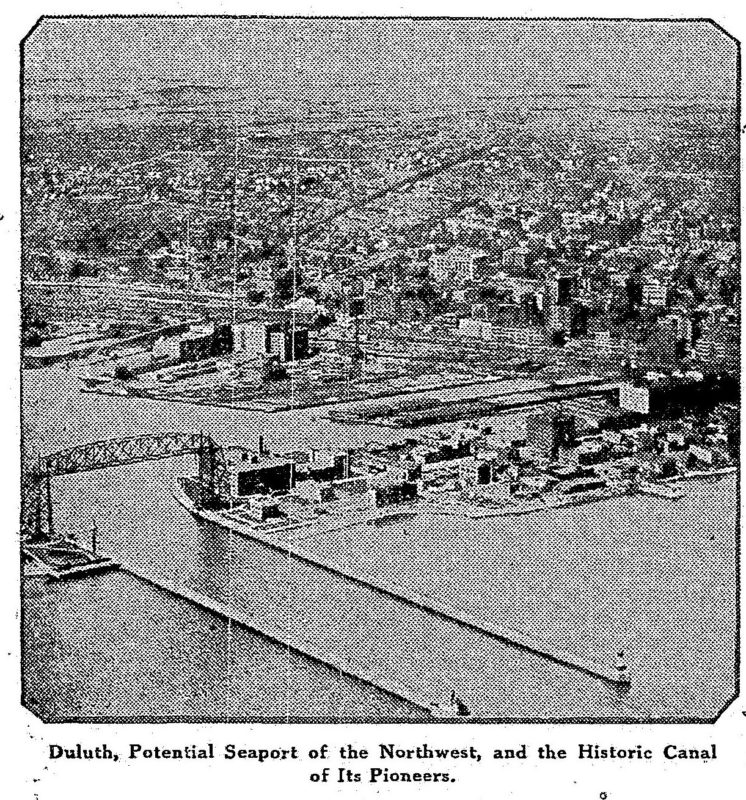

If it is possible for you to look upon the westernmost end of Lake Superior from the air you will get the idea at once. The St. Louis river, twisting down from the northwest forests toward the lake, abruptly begins to gnaw and slash at the countryside, pushing the Minnesota arrowhead away from the Wisconsin mainland, leaving jagged capes hanging like strips of torn flesh among which the waters form a chain of widening lakes and bays. But the river is suddenly confronted by one last obstinate sinew of land. Thin, yet tenacious, it holds the lake end from gaping into a broad wound. Behind it, the dammed waters spread to make St. Louis bay. At a point very close to the Wisconsin shore, and eight miles or so from Minnesota, the earthen muscle is stretched too fine, and there is a thin, ancient rip through which lake navigators since time immemorial passed from rough Lake Superior to the bay.

Fishermen, starting from the inner wharves of Duluth, had to beat a good seven miles down the bay before they could breach out into the lake; homing, they endured the same inconvenience, which was even greater if they came down from the north shore, for then they had to sail along the whole outside face of the peninsula and double on their course once they were inside–fourteen miles roundabout. The situation was a hardship to virtually the entire population of Duluth, which bad begun its career as a fishing village.

The wives of Duluth, like the women fisherfolk of Charles Kingsley’s poem, had to weep. Blows on Superior are unexpected and calamitous. Even so, I am sure that it was not in anxiety that the women shed tears. Ask one of your deep-sea sailor friends. He will bear me out that it was for shame to see how clumsily their men sailed that the women of Duluth cried, while they stood on the bluffs above town of evenings to watch for the incoming fleet. Keen-eyed old lady Maysley, who came from salt-water forbears, put it into words. “If only there was a hole down to this here end–‘would save us womenfolks a lot of dallyin’ and us’n’s menfolks from makin’ holy shows of themselves for such long spells!”

That was a reasonable idea, and it took quick hold. The city made up its mind to cut through the peninsula at its Duluth root and turn Minnesota Point into an island. Forthwith it hired a dredge and undertook its first active challenge to geography.

Not a Minute to Lose.

Word of the enterprise reached Superior. Ever since the day in the midfifties when the Nettleton brothers and a few other stalwarts had succumbed to the lure of the Minnesota bluffs and rowed away from the flat Wisconsin beach, Superior had looked upon Duluth as early New York looked upon Brooklyn; as Kansas City, Mo., looked upon Kansas City, Kan., as San Francisco of the nabobs looked upon Oakland–with a “fellow, why don’t you please go away from here?” air. But this latest annoyance could not be stared down; it required active rebuttal, for it comprised grave danger to the welfare of Superior. The people of Superior believed that it did, at any rate; they figured that a new channel on the Duluth side would scour out of the bay silt that would be diverted to the front of the natural passage on the Superior end.

Superior took pencil and paper in hand and hurried off a protest to congress. And Superior in those days, if you are to believe my friend, Seaway Sam, “was backed by a right powerful crowd of politicians and rich bankers in Washington.”

It may have been so. For the bad news that reached Duluth that Friday in April of 1871 was that congress, hearing Superior’s prayer, had answered it with an injunction against the digging of a canal by Duluth until a United States army engineer had looked over the ground. Both injunction and engineer were coming together from Fort Leavenworth in Kansas and would arrive on the first train in the morning of the following Monday. The town bell rang in Duluth within the hour of the telegram’s arrival, and when the citizenry had gathered the members of the common council spoke to them: “Clearly, this is to be a week-end of serious endeavor; of toil, and little sleep. If we depend solely upon yonder lone dredge our canal will not be finished before snow flies next autumn. The injunction will be here on Monday. How many of you have shovels?”

It was bleak down on the waterfront that early spring night; but young men and old, fat boys and lean, shed their coats and turned up their trousers and their sleeves, and dirt began to fly like “dust in a Kansas cyclone.” All night there was the singing of steel in sand; the secret odors and sounds of heavy, wet, earth; muted shouts, and the hurrying of figures to and fro in the fitful light.

Duluth Gets Its Canal.

With the dawn came the townsfolk of Superior, who had been mystified by the strange lights in the night, and now rowed or sailed over to investigate. They gathered on Minnesota Point, on the far side of the now plainly outlined ditch; and at first they jeered. But the men of Duluth turned hard looks upon them, and a few shovels were raised threateningly.

Early Monday a pompous army officer stepped off the train, not a moment too soon to see the little steam tug Fero puff and bubble and fuss her way through the canal into the lake and then turn right around and go through again, knowing she was making history, looking as though she might burst at any moment from importance–or an over-wrought boiler.

“You can’t have a canal,” the officer said, brandishing the injunction. “Maybe not.” the common council said, “but it appears mighty like we got it anyhow!”

And Duluth still has it. But instead of being a narrow ditch shored with hand-adzed planks, it is now wide and splendid, with concrete walls between which the premier ships of the world may glide without touching.

In 1930 eight thousand one hundred and ninety-eight ships, of a net aggregate tonnage of more than thirty-five million, came and departed with passengers, coal, coke, grain, limestone, iron and copper ore and dairy products. Only New York, aided by its overseas trade, leads in annual statistics the port which is known to every resident of Duluth as Duluth Harbor, to every resident of Superior as Superior Harbor, and to the federal government as Duluth-Superior Harbor.

“New York will have to take a back seat, for Duluth will be the busiest American port when the ocean comes here,” my friend Seaway Sam predicted wistfully.

When the ocean comes to Duluth!

Prophet of the Seaway.

In the year they broke through to the lake, the people of Duluth met for a purpose of wider moment. On August 8 the council hall was crowded to the lintels, yet strangely hushed, when Mayor Markell said: “Friends, Mr. Lewis A. Thomas has got something he’d like to say to us.”

Mr. Thomas spoke through a long evening, and there was neither stir nor sound. He talked quietly; for you do not have to shout when your words bear illustrious thoughts. He talked; and the walls fell away and there ran the open seas of the world. We have built our homes and cast our daily lives, he said in effect, beside the very greatest, the most truly providential, of the abundant natural resources of our laud; beside one of the sublimest of the earth’s geographical wonders–the Great Lakes. It is the only natural highway to the heart of our continent.

Except for a few links–matters easily within the skill of engineers–it is a broad, deep waterway down which we can ply at top speed in those newfangled steamships; carrying our products to all nations; and their products and their people likewise may come to us.

It is not, he said with emphasis, something intangible; something indefinite or visionary or problematical; something that must be wholly created out of nothing. This magnificent utility lies under our keels now, virtually completed; and needs only such improvements as the ingenuity of man usually imparts, for his greater comfort and service, to all means his race has found on earth. Thus he talked: and the room seemed filled with the rustling of palms and the fugitive pungency of tea bushes in hot moist fields. He finished; and there was a play of paper and pen. Soon a resolution lay upon the table. It called on congress to open the Great Lakes to the sea; and it pledged co-operation, toward the furtherance of that ideal, with sister towns and states of the lakes and their hinterlands. That was the beginning.

Other Great Lakes cities, aspiring in their own rights, might each have its notion as to which is going to be the metropolis; and your reporter is a peaceable fellow who loves everybody and takes no sides. None of its allies, however, withhold from Duluth credit for sole possession of the sentimental baton in the National Seaway movement, so called. If they did, their opponents would set them right. The anti-Seaway men know their foes. And it is upon the name and pretensions of Duluth that they call down the utmost ridicule. Duluth does not mind. Business men of Duluth, and of the whole territory involved in her fate, seem convinced that Seaway obstructionism is due not at all to honest conclusions, but wholly to provincialism and selfishness. Indeed, the existence of this belief among all classes is undeniable, and grave because it is so widespread. The farmer, every bit as much as the miller; the miner, quite as strongly as the operator; the cashier, equally with the banker, believe that the economic salvation of the north Middle West lies down the lakes and the St. Lawrence to the sea.

Seaway Sam Speaks.

I asked my friend, Seaway Sam, to interpret these convictions for us; also, to justify Duluth’s passion for the Seaway, and its certainty that the Seaway will be built. No one is better qualified to do so. He is called Seaway Sam by his fellow citizens, not in derision, but in affectionate tribute to the selfless zeal with which he has studied the Seaway until every aspect of it lies resolved at his mental finger tips, so that when he speaks it is not as an individual, but as the informed mouthpiece of his city.

“If the political tempers and circumstances of today,” he said, “were similar to those of sixty years ago–secession times–the mood in a dozen powerful states would be to secede and join with Canada in the construction of the Seaway. We have the three essentials to self-sufficient human society: agriculture, mining and forests. We need only unrestricted transportation facilities. With access to the ocean, Duluth, Superior, Milwaukee, Green Bay, Toledo, Sandusky, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and all the other cities and states on the lakes or adjacent to them would be quite independent of New York and the eastern, southern and far western states that have conspired to keep our commercial wings clipped.

“Fargo, North Dakota, for example, would be only a little more than 200 miles, Bismarck less than 450, from an ocean port, instead of 1,500 and 1,700 respectively from the New York seacoast. Think over our roster of cities and states, the list of those marooned from ocean traffic and handicapped in competition with the low rates available to seacoast cities and states through the Panama canal. We should have comprised a separate nation of some caliber, eh? Secession is fantastic today, beyond all sane thought; but sections can be alienated by the cupidity of others, and the ill-will and bitterness and lack of co-operation for the common national good with results that are ugly enough.

“All we seek is the improvement of a living utility. That is what makes us sore: the knowledge that the world’s greatest ships could today steam at full speed, unhindered, over 90 per cent of the 2,400 miles from Duluth to the Atlantic.

“Foreign ships can now come into the lakes. Prows that have furrowed the seven seas, from Russia to Rangoon, have touched the wharves of Chicago and Duluth. But these ships that come now are small; of fourteen foot draft, or less. By improving–not building, mind you–10 per cent of the present Seaway so as to permit the passage of ships of 25-foot draft, we would open the Great Lakes to more than 80 per cent of the world’s tonnage.

Complete–With Alterations.

“The Seaway, of course, means the five Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence river, which connects them with the Atlantic ocean.

“Sailing from Duluth eastward, we have 338 miles of deep water before we reach the first step, 21 feet down in the falls of St. Mary’s river connecting Superior with Huron. There are four American and one Canadian locks here now, 21 feet deep. One new lock would be required, and deepening of all. In 1929 more than 90,000,000 tons of freight passed through these Soo locks in the lakes season of eight months; compared with 64,000,000 tons for the Panama and Suez canals together over the full year. Now we are on Lake Huron, full speed ahead.

“If we had started our trip from Chicago or Milwaukee or any other Lake Michigan port we should have come into Huron through the Straits of Mackinac, without trouble. We race 223 miles along Huron to the next step down, 9 feet, through the river and lake of St. Clair, and the Detroit river. Here there is a 21-foot channel, without locks; and only dredging is required. We speed down Erie, 240 miles, and come to the biggest step the route takes in its course from Superior to the ocean–326 feet, divided between Niagara falls and the Niagara river gorge. In 28 miles and through 25 locks the Welland canal lets us down into Lake Ontario. Here only soft dredging is required to give us a 27-foot channel.

“Now, a last spurt of 180 miles along Lake Ontario takes us to the St. Lawrence. The fourth step, 226 feet down, spreads through the various rapids between here and Montreal. Locks and dredging are necessary. Once we pass Montreal we have clear sailing in a 30-foot channel to the ocean, and we’ll never notice the fifth step of 20 feet. Altogether, then, to bring the ocean to Duluth, there are 2,429 miles that don’t need a penny or a thought; and 258 miles that require certain work.

“You are familiar with the objections raised to the Seaway and with the source of these objections. Many of them are misunderstandings; others have been proved to be mistakes; but the most of them are propaganda–mean prejudices, or just bald falsifications.

“The cost–estimated on 1926 levels; probably less now–to the United States is figured at §272,500,000. Through a power agreement with the state of New York, the actual cost to the federal government would be in the neighborhood of $150,000,000.”

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments