Historical Trauma and Standing Rock

When I was young and more exciting than I am now, I started teaching Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus. One of the reasons Maus made its way into classrooms was that it was an immensely accessible introduction to the Holocaust.

When I was young and more exciting than I am now, I started teaching Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus. One of the reasons Maus made its way into classrooms was that it was an immensely accessible introduction to the Holocaust.

But about halfway through the second time I taught the book, I realized that its special genius is not the way it tells the story of Vladek, a Holocaust survivor, but the way it tells the story of Artie, the son of a Holocaust survivor.

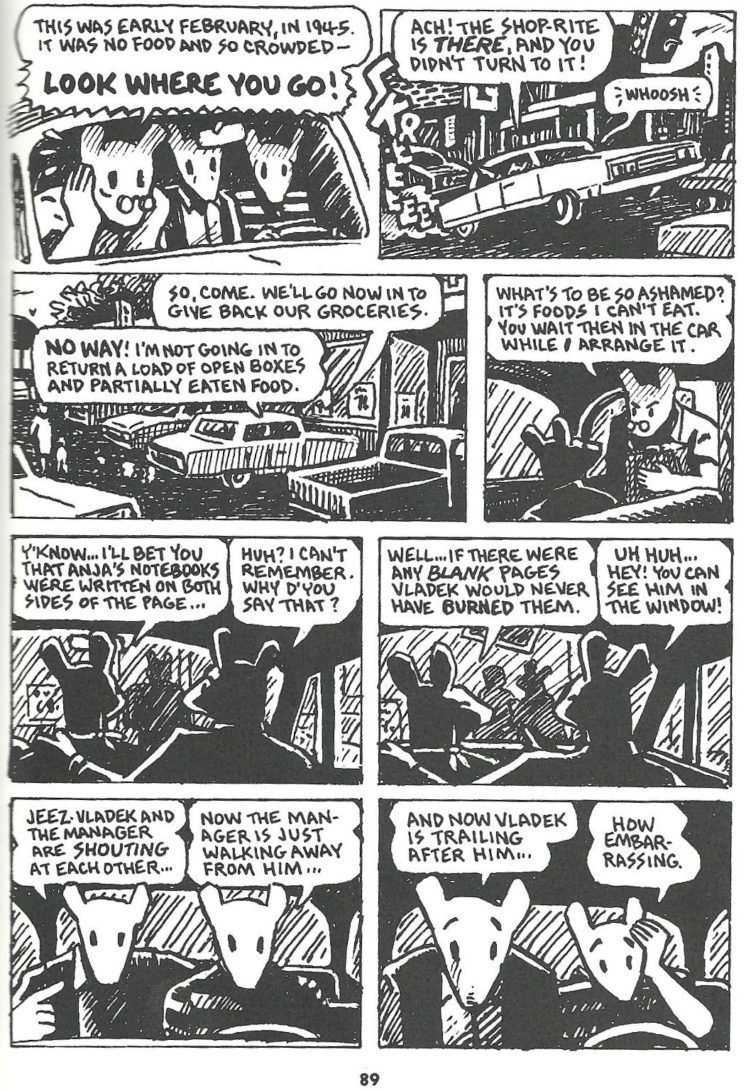

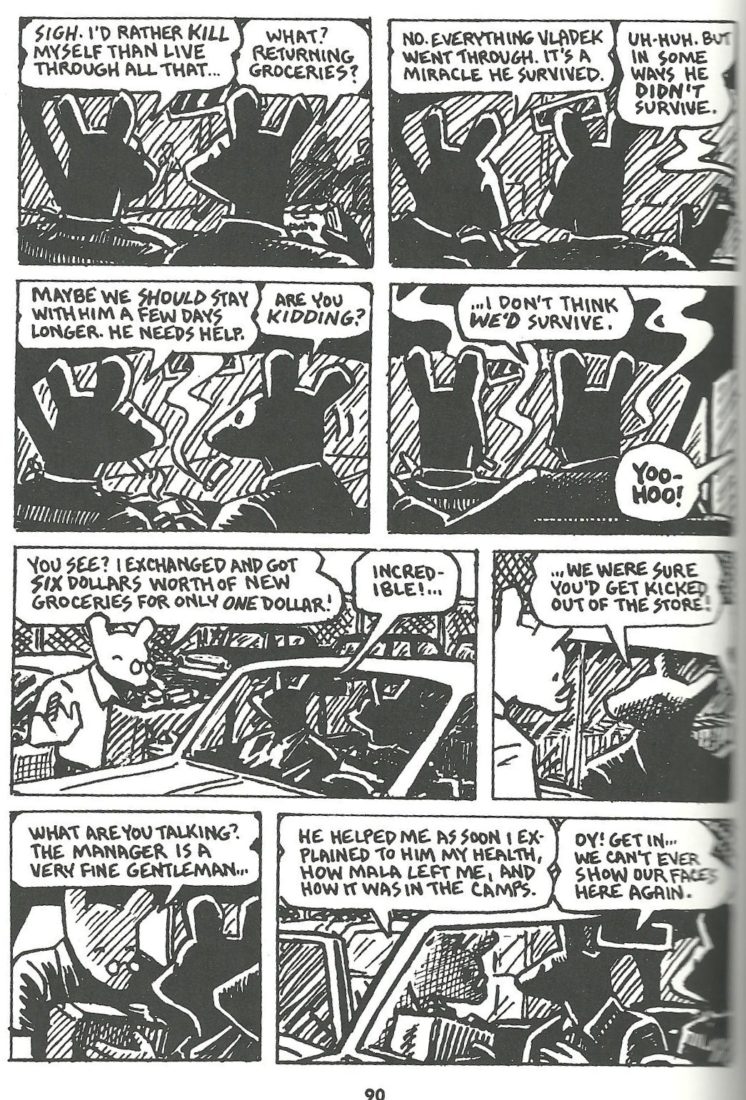

Perhaps this is clearest in the scene where Artie and his wife, Francoise, take Vladek to the grocery store so that Vladek can return a half-eaten box of cereal.

Why does Vladek want so much to return a partially eaten box of cereal? Because he remembers a time, in the camps, when every scrap of food was essential.

Why is Artie mortified? Because when his father tells the manager his story, Artie can’t tell whether his father is offering an explanation or an ad misericordiam, the Latin term for an appeal from pity. Does the manager really understand Vladek’s experience? Is the manager extending a kind of pity to a Holocaust survivor? Artie presumes pity, and so becomes embarrassed.

It’s clear that Artie barely understands how his father’s survival story has affected Artie himself, much less how other people might respond to it. Artie spends years writing Maus in an attempt to understand how his father’s experiences have shaped his life.

To be honest, very few of us understand the ways that historical traumas (or historical events more broadly) have impacted our lives. We are like a domino halfway down the line in a series of dominoes that have been struck by a finger hitting a first domino …

… fifty or

… … … one hundred or

… … … … … a thousand dominoes in line before us.

It’s not clear to us, in the moment, that the strike of the first domino has resulted in our falling over, but the relationship between cause and effect would be hard to deny.

* * *

The historical experience that shapes contemporary life doesn’t need to be as brutal as the Holocaust.

I brazenly throw out every plastic bag from every loaf of bread I buy. My great-grandparents saved every bag, placing them in a drawer next to the toaster, right below the cabinet filled with empty plastic butter containers. (They called those containers “Tupperware,” a kind of thumb in the eye of people who paid money for name-brand plastic food containers.)

At any given moment, there were dozens of those bags and twist ties in the drawer, and half a dozen plastic containers in the cabinet, because my great-grandparents lived through the Great Depression. In those years, everything they needed cost more than they could afford. Everything potentially useful needed to be saved. As a kid, I promised never to do that, to never fill a drawer with bags that belonged in the trash. I could never be like them.

I looked at my great-grandparents the way Artie looked at Vladek. I thought my great-grandparents were quirky, if not crazy, because I never experienced the psychology of scarcity that they lived with for years. As I grew up, I came to understand why they did irrational things. Those irrational things would have been entirely rational in another moment, as part of the earlier story of their lives.

I fully expect that if my life is blessed with the children I desire, they will decry my wanton wastefulness, which is a rejection, a reverberation of my grandparents’ desire to save everything. If butter is still packaged in tubs in twenty years, I expect they will save every last one. Their father, after all, was so wasteful. They could never be like him.

In that way, we can see that my children’s behaviors, in a very small way, may be shaped by the experiences of their great-great grandparents. As one scholar notes, “Even family members who do not have a direct experience of the trauma itself can feel the effects generations later.”

* * *

The University of Minnesota talks about historical trauma this way:

Historical trauma is not just about what happened in the past. It’s about what’s still happening.

This is visible in an indirect way, as “health disparities, substance abuse, and mental illness are all commonly linked to experiences of historical trauma.” The effects of the past are still happening. The Standing Rock Reservation is on my mind as I think about this.

The American Psychological Association reported on intergenerational historical trauma at Standing Rock Reservation in 2003, writing about “Denise Casillas, a half Lakota, half Latina single mother” who wanted to understand “a cycle of violence, extreme poverty and substance abuse” and “a slew of teenage suicides.” The researchers found that historical trauma shapes the challenges faced by the residents today.

The current president of the APA, Susan H. McDaniel, says that “chronic, systemic loss and mistreatment … may lead to historical trauma in which the pain experienced by one generation transfers to subsequent generations through biological, psychological, environmental, and social means.” Standing Rock was an open wound before the heavy equipment began turning the earth.

And when the heavy equipment arrived, it was history that the equipment made bleed, again. According to Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Chairman David Archambault II, “these grounds are the resting places of our ancestors. The ancient cairns and stone prayer rings cannot be replaced. In one day, our sacred land has been turned into hollow ground.” To make this possible, the construction crews used dogs and water cannons to move protesters.

It’s impossible to imagine what it must be like to live life in a community known to be suffering from the effects of historical trauma and to feel those traumas re-enacted with dogs and water cannons.

The University of Minnesota recommends that “reconnecting people to the vibrant strengths of their ancestry and culture, helping people process the grief of past traumas, and creating new historical narratives can have healing effects for those experiencing historical trauma.” In one fell swoop, construction workers cut off “the vibrant strengths of their ancestry and culture,” and they made impossible “new historical narratives [that] can have healing effects.” The only story that can be told from Standing Rock is one in which the trauma recurs, over and over.

In Duluth, multiple organizations have made statements of support for the protestors at Standing Rock. Peace United Church of Christ held a vigil. The Red Cliff Band has been present at the protest site. In reflecting on Standing Rock, in this way, I wanted to be able to nod to these efforts as well as invite (in the comments) more folks to announce other efforts worth participating in.

But I also wanted a gentle way to introduce the notion of historical trauma, and to remind those folks who may see a pipeline as an acceptable environmental risk that we are dealing with more than a risk to clean water. We are reopening the traumas of the past and perpetuating “health disparities, substance abuse, and mental illness” into the future.

I have no idea what we can do. I have no idea how to heal the wounds that history created and bulldozers reopened. Elder Atum Azzahir, as cited by the University of Minnesota, tells us what one path is, and I hope it’s not too late to start down this path together.

We have words for the trauma we are enacting, in the present, at Standing Rock. Is it too late for stories, songs and poems to heal?

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

4 Comments

Helmut Flaag

about 8 years agobhall

about 8 years agodoubledutch

about 8 years agoDavid Beard

about 8 years agoThe feedback on this piece reminds me to think harder about *choices*: Helmut, you are right. I know that film plastic bags are recyclable, and I make the choice not to recycle them because they are not part of curbside pickup. That's a choice, one with implications for this story that I hadn't thought about because, as you correctly note, I am contributing to the petrochemical dependency that created the pipeline controversy. Thank you for that reminder. DoubleDutch, I made choices in writing this that hurt my ability to achieve my intent. I only included direct links to two indigenous voices, a few more as reported in non-indigenous media. Linking to more indigenous voices, present at the protest, would have strengthened a sense of what is positive in the community or protest at Standing Rock. Thank you for that reminder. Beyond that, though, is the more central question of whether in writing this essay, I shined too much light elsewhere, on myself. I saw writing this essay in the way I see talking to people who do not understand (and sometimes deny) arguments about historical trauma. That resistance comes in two forms: 1. Resistance to the idea that our history shapes our actions. To these people, problems like "health disparities, substance abuse, and mental illness" are problems that begin and end in the lifetime of the individual. To these people, health disparities are about lifestyle choices, substance abuse is about character choices, and mental illness is resolved by a prescription. They refuse to acknowledge historical forces on contemporary struggles. I want, we need, to acknowledge those historical forces. 2. Resistance to acknowledging historical forces on contemporary life is often rooted in a confusion between (a) claims about historical trauma and (b) claims about "collective guilt." ("My family didn't even own slaves." "My family wasn't even here when the atrocities of the 19th century were committed against indigenous people.") Acknowledging historical trauma does not need to mean acknowledging collective guilt. My example (about the behaviors of people who survived the Depression and the legacy of those behaviors three generations later) is about establishing the existence of historical trauma without getting caught up in collective guilt. You can't blame anyone for the Dust Bowl. The historical trauma of the Depression shaped my grandparents without creating any possibility of guilt. If a reader can accept that the Depression shaped my grandparents, my mother, and me, then we can inch toward whether the historical events of the nineteenth century can still shape people alive in the 21st. If we can recognize the historical dimension of Standing Rock, not just the environmental dimension, we can understand more of what is at stake. We aren't just risking losing the quality of water. We risk losing the possibility of healing those historical wounds. I hoped that I was not writing about me, but explaining something difficult in a way that some readers might accept without becoming defensive. But I made a choice not to make that more explicit, and so I ran the risk of confusing my readers. Thank you for that reminder to be more careful in my choices. And thank you for the reminder to celebrate the act of resistance and survival, the reminder that healing is still possible. BHall, thank you for making the choice to share where more can be done.