The truth about Shakespeare in Duluth

2016 has been full of 400th anniversary observations of Shakespeare’s 1616 death. Having first read Shakespeare in Duluth, I was thrilled to return for my hometown’s own First Folio celebrations, from the exhibit at the Tweed Museum to an early music concert. It was an honor to speak at St. Scholastica, where I was once part of the crew for Cymbeline, with librarian Todd White as the baddie Iachimo. At the Marshall School, I did the lighting for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, starring Maria Bamford (Titania) and Katie McGee (Puck) under the direction of Tim Blackburn. (Our Marshall librarian Louis Jenkins recently teamed up with Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance.)

Caught up in the quatercentennial excitement, it’s easy to become fixated upon what Shakespeare supposedly thought, rather than how he thought — that is, what kind of education led him to think the way he did. I take as an example of this misguided fixation myself, 25 years ago. My 1991 yearbook profile includes the usual pimply portrait scribbled over by classmates’ farewells. For my motto, I selected a quotation from Hamlet: “To thine own self be true, and it shall follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.”

Caught up in the quatercentennial excitement, it’s easy to become fixated upon what Shakespeare supposedly thought, rather than how he thought — that is, what kind of education led him to think the way he did. I take as an example of this misguided fixation myself, 25 years ago. My 1991 yearbook profile includes the usual pimply portrait scribbled over by classmates’ farewells. For my motto, I selected a quotation from Hamlet: “To thine own self be true, and it shall follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.”

And I of course attributed those words to Shakespeare.

Unwittingly, I was doing what countless others had done before: quoting a dramatic passage out of its ironic context, and acting like Shakespeare said it himself, rather than a fictional character. Shakespeare’s words circulate far beyond their origins, whether in 17th century manuscripts, 18th century novels, 19th century poems, 20th century cinema, or 21st century politics.

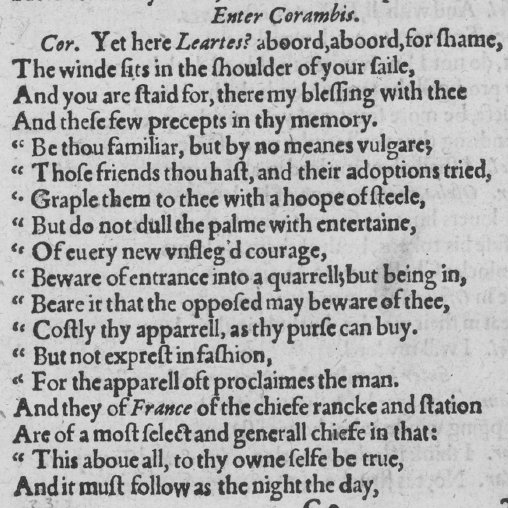

In this case, the words come from a father tediously reciting a cascade of bland proverbs to his departing son. The advice should already be suspect. But what’s fascinating about this speech is the peculiar way it was printed in the 1603 first Quarto. Why does the left margin include a series of quotation marks?

In this case, the words come from a father tediously reciting a cascade of bland proverbs to his departing son. The advice should already be suspect. But what’s fascinating about this speech is the peculiar way it was printed in the 1603 first Quarto. Why does the left margin include a series of quotation marks?

They are typographic flags, guiding you to recognize these as sententious phrases, and to transcribe them in your commonplace book. In such a notebook, an aspiring young thinker could gather choice thoughts for further reflection. A writer like Shakespeare might archive new words, plot outlines, and snippets of conversation. Again: what Shakespeare “said” (a banal truism in the voice of a dull toady) is far less interesting than how he came to say it.

This focus (on the how, not the what) helps us return Shakespeare to his dynamic, interactive environment of the school and theatre, rather than treating him as an isolated genius — something anniversary celebrations often risk doing.

1617 German broadside from The British Museum

When was the first centennial observed? It took place the year after Shakespeare died, on the 1617 anniversary of the German Reformation. A satirical woodcut makes Luther’s gigantic pen knock the crown off of the Pope. As one commentator quips: “I imagine someone here saying, ‘abandon Pope all ye who enter here,’ or Luther with the pen saying, ‘it’s the quill of God,’ or a lot of very strict Catholics saying, ‘yes, but your interpretation is much Luther.'” As you can instantly see: anniversaries often have a polemical edge.

The first major Shakespeare anniversary was the 1769 Jubilee, orchestrated by actor David Garrick in Stratford. This gala gave birth to the Shakespeare tourism industry, and the cult of “the Bard,” in which the mythology of Shakespeare as a unifying national figure trumps the actual engagement with his works. Strikingly, Garrick’s Jubilee, while full of pomp and memorabilia (like this entry ticket), did not involve any recitations from the plays or poems! (In contrast, it’s a credit to Krista Twu that so many Duluth organizations have planned such an impressive array of performance-related programming this month.) But it did include an “Ode” by Garrick himself, opening with these bardolatrous lines:

To what blest genius of the isle,

Shall Gratitude her tribute pay,

Decree the festive day,

Erect the statue, and devote the pile?

. . . ‘Tis he! ’tis he! — that demi-god!

. . . ‘Tis he! ’tis he!

‘The god of our idolatry!’

Anniversaries risk partisan factionalism (as with the Lutheran image) or over-idealization (as with Garrick’s festival). As James Shapiro has demonstrated, the 18th century praise of Shakespeare as an isolated genius led to a counter-reaction in the 19th century: the emergence of conspiracy theories proposing alternative candidates for authorship.

Houghton Library, Harvard University

People tend to see in Shakespeare what they want to see. Often this involves a chauvinistic projection of the author’s own self: lawyers, for instance, sometimes presume that Shakespeare must have been a lawyer. As it happens, two such lawyers had ties to Duluth. (A third, to his credit, concluded that Shakespeare was the real Shakespeare.)

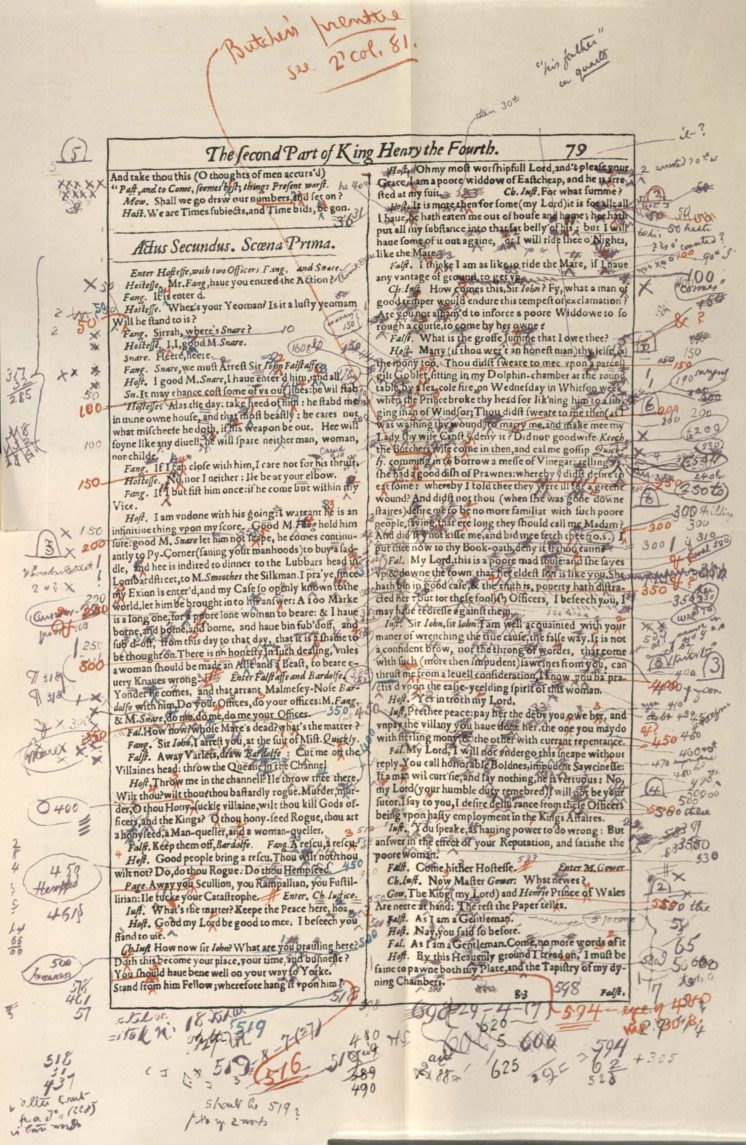

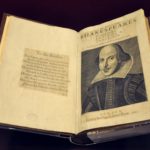

The more outlandish one was Ignatius Donnelly, a Minnesota Congressman during Reconstruction (1863–69) and railway lobbyist on behalf of financier Jay Cooke. In 1888, Donnelly published The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays. Donnelly’s copy of the First Folio furiously overflows with mathematical annotations to ‘prove’ Bacon’s covert authorship. Donnelly treated the Folio as an iconic, almost mystical object, one worthy of minute scrutiny to ‘reveal’ its secret code. This manic debunking is the disturbing inversion of Garrick’s hyper-idealization of Shakespeare.

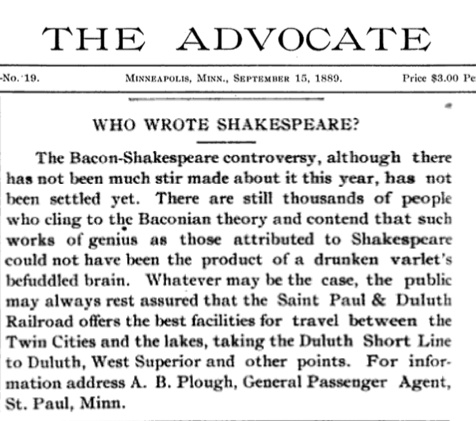

It was likely Donnelly whom a Minneapolis newspaper had in mind when it published this comical notice in 1889:

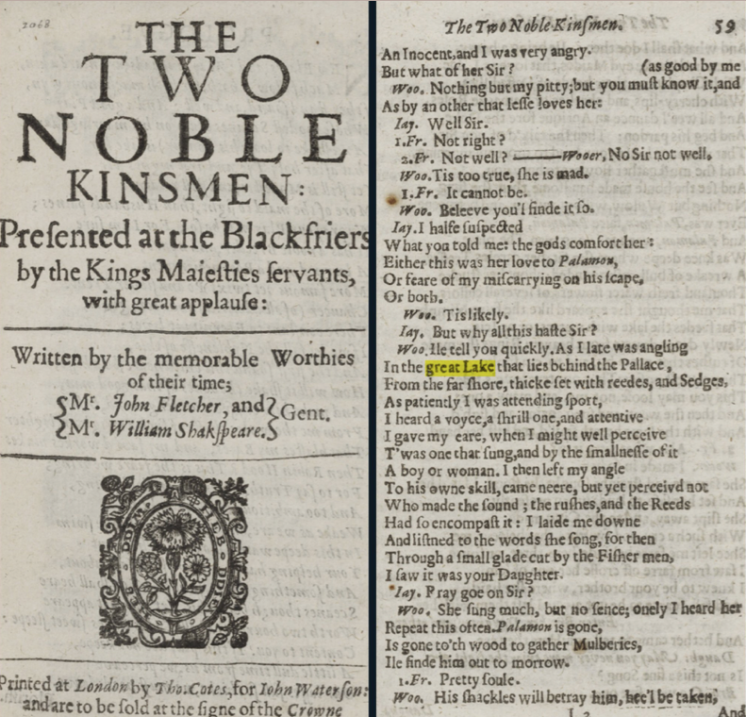

Rather than getting derailed by the myth of self-born genius, it’s more effective (and more accurate) to consider Shakespeare as a craftsperson. A craftsperson works closely with others in a highly skilled environment in order to make something — in this case, plays. As Paul Cannan helpfully reminded us at the opening reception for the First Folio, collaboration between playwrights was more the norm than the exception in Shakespeare’s era. (One of Shakespeare’s last collaborations, The Two Noble Kinsmen, was discussed by Nickolas Haydock as part of the Scholastica conference.)

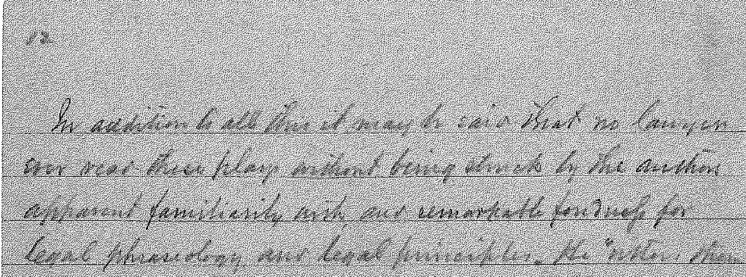

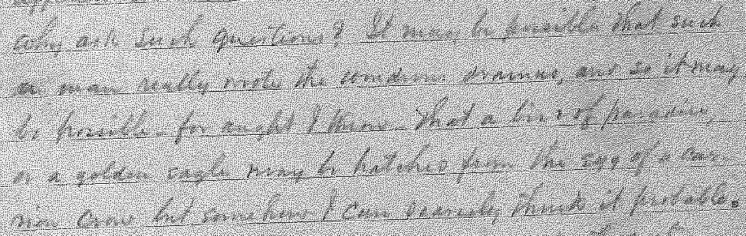

Another late 19th century American Shakespeare conspiracy theorist was James Proctor Knott. Archivist Jonathan Jeffrey helped me locate an unpublished Shakespeare lecture by Knott; the two excerpts reproduced here appear courtesy of Library Special Collections, Western Kentucky University.

Like Donnelly, Knott was a lawyer who presumed that Shakespeare’s plays must have been written by (not surprisingly) a lawyer:

“In addition to all that this it may be said that no lawyer ever read these plays without being struck by the author’s apparent familiarity with and remarkable fondness for legal phraseology and legal principles.”

This presumption aligns with Knott’s incredulity that someone from Shakespeare’s background could have written the plays:

“It may be possible that such a man really wrote the wondrous dramas, and so it may be possible — for aught I know — that a bird of paradise, or a golden eagle may be hatched from the egg of a common crow, but somehow I can scarcely think it probable.”

Snidely dismissing Shakespeare as a common “crow” was exactly what Elizabethan dramatist Robert Greene did early in Shakespeare’s career (1592):

“there is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that, with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bumbast out a blanke verse as the best of you; and being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrie.”

Greene was likely alluding to the Aesop fable in which a crow (or jackdaw), yearning to emulate other birds, adorns himself with their plumage – for which they violently attack him.

Melancholic jackdaw attacked by peacocks (1479), Victoria and Albert Museum

Yet this metaphor aptly conveys the canny ways in which Shakespeare borrowed material. To invoke just one example of him plucking plumes, recall the famous Christopher Marlowe passage where Doctor Faustus marvels at the apparition of Helen of Troy:

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Shakespeare repeatedly tropes on this “was this the face?” line, from the deposition scene of Richard II —

Was this face the faceThat every day under his household roof,

Did keep ten thousand men? Was this the face

That like the sun did make beholders wink?

— to Troilus and Cressida, in reference (like Marlowe) to Helen of Troy:

She is a pearl,Whose price hath launched above a thousand ships.

There are scores of such lines lifted not only from his peers but also from medieval poets, classical authors, and contemporary polemicists. (One scholar gathered eight volumes worth of these sources.)

Knott was also a witty politician (perhaps even one whom Ignatius Donnelly was lobbying for Cooke’s railroad subsidies). Here’s Knott’s equivocation when queried whether he preferred Hamlet or Macbeth:

“My friend, don’t ask me that question. I am a politician, and a candidate for reelection to Congress; my district is about equally divided; Hamlet has his friends down there, and Macbeth his, and I am unwilling to take any part between them!”

But in Duluth lore, James Proctor Knott is renowned for the satirical speech he delivered to Congress in 1871. Dismayed at what he considered a boondoggle subsidy for a Wisconsin railroad, Knott hyperbolically praised the then-small town of Duluth. His ruthless mockery brought roars of laughter — and death to the bill.

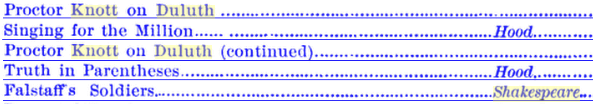

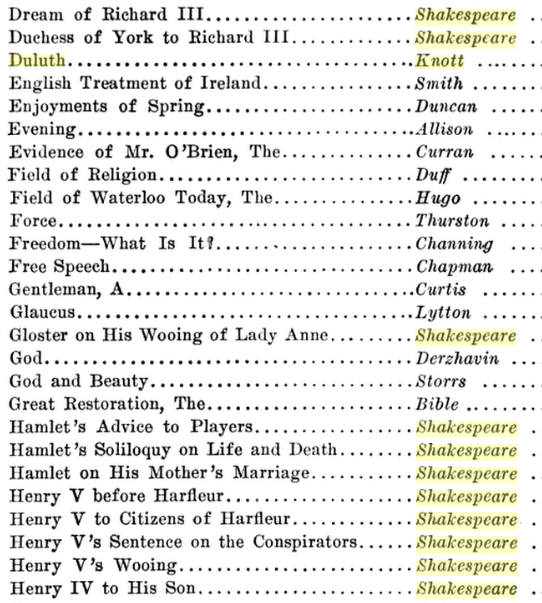

Knott’s oration gained instant notoriety, and was quickly reprinted and anthologized, as in Benjamin Bussey’ Huntoon’s 1874 The American Speaker:

“Duluth” appeared alongside passages from Shakespeare, as in the 1909 volume Natural Drills in Expression gathered by Arthur Edward Phillips:

In fact, Knott remains in print, in William Safire’s anthology of “great speeches in history,” with the appropriately Shakespearean title Lend me Your Ears.

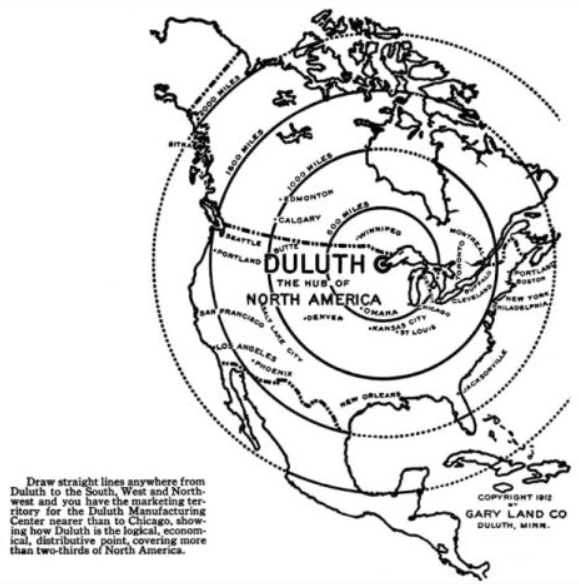

Image courtesy of the Kathryn A. Martin Library Archives and Special Collections, University of Minnesota, Duluth

Part of what made Knott’s speech so uproarious was his demonstration of a map that placed Duluth at the center of North America: “there, there for the first time, my enchanted eye rested upon the ravishing word ‘Duluth.’” Local promoters appropriated Knott’s ridicule to their own ends, producing similar maps that boasted: “ALL ROADS LEAD TO DULUTH.” What had begun in lacerating jest eventually became shameless boosterism by civic leaders: “DULUTH THE HUB OF NORTH AMERICA”.

In 1890, when the city had grown to over 30,000 residents, Knott was even invited to Duluth as guest of honor. To commemorate the visit, his 1871 congressional speech was reprinted alongside his 1890 address, with this triumphant conclusion from Duluth advocates:

OUR REASONS WHY

Duluth and vicinity is the best

place in which to

invest.

In reading the preceding pages you have probably smiled and perhaps as Shakespeare says, “The heaving of my lungs provoked me to ridiculous smiling.” [a quotation from Love’s Labour’s Lost] Undoubtedly others have smiled before you and after you have read his speech of nearly twenty years later and begin to realize how wonderfully his sarcasm has become a reality — you will want to turn back and “smile some more” — but it is not my intention to keep you in a hilarious mood, but would rather you would put on your thinking cap and see if you can realize what the statements in these few pages mean.

By the late nineteenth century, Duluth’s prominence made it a regular stop on major national cultural circuits: the 1887-88 theatrical tour by eminent Shakespeareans Edwin Booth and LawrenceBarrett went through Buffalo, Detroit, Minneapolis, Duluth, Chicago, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Boston, New York, Baltimore, Richmond, New Orleans, Atlanta, Nashville, and Memphis.

In jest, Knott’s map had shown Duluth as being (preposterously) near the latitude of London. Yet as writer Frank Ernest Hill would later point out, Shakespeare’s London c. 1600 was about as populous as Duluth c. 1950 (i.e. 100,000 people):

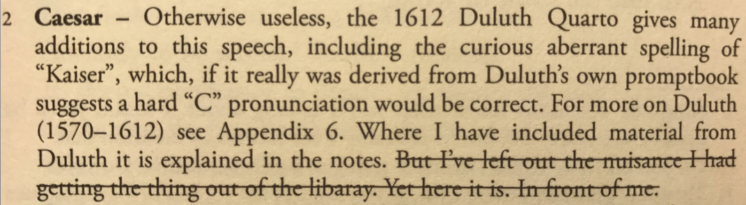

By the 1960s and 1970s, as deindustrialization and soaring unemployment contributed to Duluth’s declining population, the city more frequently served as a cultural punchline than the home of Knott’s “untold delights.” There’s even a Duluth joke found in the pseudo-scholarly notes for collaborations between Shakespeare and Dr. Who. In the annotations, an unnamed editor claims to be examining the “1612 Duluth Quarto,” supposedly by a Shakespearean actor named Duluth (1570–1612):

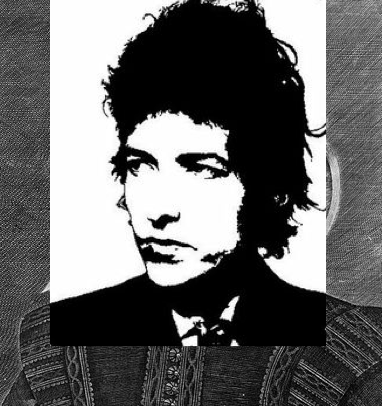

I would be remiss if I didn’t nod to Duluth native Bob Dylan, of whom “Like a Rolling Stone” organist Al Kooper once proclaimed “Bob is the equivalent of William Shakespeare. What Shakespeare did in his time, Bob does in his time.” As many others have cataloged, Dylan alludes to Shakespeare throughout his lyrics.

But again it’s worth reflecting upon the process of artistic creation, rather than what’s actually said. And here Dylan is in accord with the ways in which tradition informs an artist’s work. In a 2015 speech, Dylan acknowledged: “These songs of mine, they’re like mystery stories, the kind that Shakespeare saw when he was growing up. I think you could trace what I do back that far. . . . These songs didn’t come out of thin air. . . . It all came out of traditional music . . .”

But again it’s worth reflecting upon the process of artistic creation, rather than what’s actually said. And here Dylan is in accord with the ways in which tradition informs an artist’s work. In a 2015 speech, Dylan acknowledged: “These songs of mine, they’re like mystery stories, the kind that Shakespeare saw when he was growing up. I think you could trace what I do back that far. . . . These songs didn’t come out of thin air. . . . It all came out of traditional music . . .”

As New Yorker editor David Remnick celebrated Dylan’s Nobel: “his primary influence is the history of song, from the Greeks to the psalmists, from the Elizabethans to the varied traditions of the United States and beyond: the blues; hillbilly music; the American Songbook of Berlin, Gershwin, and Porter; folk songs; early rock and roll.” Like so many creators, Shakespeare and Dylan gather and absorb material from the past, remixing it into something rich and strange.

Dylan and Shakespeare have even shared the occasional rhyme. Christopher Ricks, a tireless champion of Dylan’s lyricism, noted that “rhymes for truth are few . . . perhaps the only word into metaphorical relation with which a rhyme can creatively bring truth [is] the word youth,” citing the first quatrain of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 138:

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutor’d youth,

Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties.

Ricks then observed that Dylan’s “Something There Is about You” “deftly supplements his rhyme of youth and truth with the names of Ruth and Duluth“:

Thought I’d shaken the wonder and the phantoms of my youth

Rainy days on the Great Lakes, walking the hills of old Duluth

There was me and Danny Lopez, cold eyes, black night and then there was Ruth

Something there is about you that brings back a long forgotten truth.

London’s Old Vic Theatre just announced that it will produce Girl from the North Country, a new play about Depression-era Duluth, set to songs by Dylan. It’s fitting that Dylan’s Duluth will be coming to London, just as Shakespeare’s London is now in Duluth. As the Folger Shakespeare Library pointed out, even The Two Noble Kinsmen seems to anticipate being on the “great Lake.”

Scott L. (Newstrom) Newstok directs the Pearce Shakespeare Endowment at Rhodes College in Memphis — way down on Highway 61.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments