Sixteen Years on the Superior Hiking Trail: Swamp River to Cascade River

Digital cameras existed in the year 2000, but it wasn’t until about 2003 that using one became mainstream. I started my quest to complete the Superior Hiking Trail with a cheap 35mm pocket camera and a roll of black and white film … perfect for capturing lush fall colors. A grand total of four photos were taken during this five-day hiking trip.

Digital cameras existed in the year 2000, but it wasn’t until about 2003 that using one became mainstream. I started my quest to complete the Superior Hiking Trail with a cheap 35mm pocket camera and a roll of black and white film … perfect for capturing lush fall colors. A grand total of four photos were taken during this five-day hiking trip.

By contrast, I have 35 photos and three videos from a five-minute window when I finished my hike in 2015. So the world has changed a bit. I worked for a newspaper then, I work for a website now. The World Trade Center buildings stood then, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum stands now. Time marches on at a faster pace than my hiking boots, apparently. My first trip covered nearly 60 miles of trail, however, and that’s not too shabby. Unfortunately, things slowed down after that.

On the sunny afternoon of Sept. 23, 2000, my friend Jeff and I drove the winding way of Highway 61 to Grand Portage. It’s not a place that is necessary or practical to go when seeking the start of the Superior Hiking Trail, but it’s a fun location to stop and look out over Lake Superior while there’s time to kill on the day before the adventure begins.

Maybe an hour before sunset we arrived where Otter Lake Road meets Swamp River near the Superior Hiking Trail’s northern terminus at “270 Degree Overlook.” At the time, I didn’t really consider the overlook to be part of the SHT. My old guidebook didn’t mention it at all, though it did show a line on a map to indicate the start of the Border Route Trail, the first mile of which leads to the overlook, which is now regarded as the SHT terminus.

So, in retrospect, by hiking to the overlook I had already completed the first mile of my 300+ mile journey, but at the time I was under the impression my mission wouldn’t officially start until the next morning.

Jeff and I built a sloppy fire and shot the breeze. I’m sure a few beers were involved, though I don’t really recall. The photographic evidence seems to indicate a can of what is quite likely some macro-brewed pilsner near Jeff’s chair.

While I don’t remember any of the conversation, I do recall the feeling that we were both on the eve of parting ways for separate adventures, and it would be a long time before we sat around another fire to recap. He would soon be on an airplane heading to the other side of the world, where he would remain for three years. And I would be on a leisurely hike, where I would remain for five days.

Since I would still have my car 20 feet away on my first night in the woods, it was the perfect opportunity to test out the bivy sack I had loaned from a friend. If I could sleep comfortably in that tiny one-man cylinder of a tent, I’d bring it along. Otherwise it would go back in the trunk and a large, clumsy four-person tent would have to ride my back to future campsites.

As fortune would have it, the most miserably cold night of my 16 years on the SHT was the very first night. I know temperatures were below freezing, because my water was solid the next morning. I slept not a wink. It was a fitful night of tossing and turning and trying to squeeze into the fetal position to retain enough heat to stop the incessant chattering of my teeth. I don’t recall if Jeff stayed up all night by the fire or slept with any degree of comfort in the large tent, I just knew then that it was my first night of the trip and out of principle I couldn’t go crawling into the car for heat.

When the sun came up it was immediately much warmer, and cold would never hamper my sleep again on the trail. I tossed the fancy bivy into the trunk and packed up the Target tent. I was eager to get started, so I said my farewells and hiked a little way up the trail to pose for my one and only start-of-the-trail photo.

When the sun came up it was immediately much warmer, and cold would never hamper my sleep again on the trail. I tossed the fancy bivy into the trunk and packed up the Target tent. I was eager to get started, so I said my farewells and hiked a little way up the trail to pose for my one and only start-of-the-trail photo.

Then off I went on the poorly maintained northernmost section, where the dewy wet grass at times was as high as my waist, which meant spending the morning trudging along in sopping wet jeans long after I reached better conditions.

I saw one other human being on my first day of hiking, a middle-aged man hunting grouse. On remote parts of the trail, late in the season, it’s possible to not run into a soul.

My first campsite was at Woodland Caribou Pond. I set up my tent immediately, while there was still daylight, and sat down for a peanut butter and jelly-slathered bagel. About halfway into the meal, I started hearing branches snapping in the distance and the grunt of what was obviously a large mammal.

Here I am, alone in the woods, sitting on a log with open containers of peanut butter and jelly, and instantly a black bear is on his way to check things out. Sure, black bear are very rarely inclined to attack humans, but if this one is hungry it will probably huff and mock charge and scare the bejesus out of me while insisting on having its way with my Thomson Berry Farms strawberry rhubarb.

So, in the most ridiculous manner possible, I begin shouting in order to ensure the bear isn’t surprised by my presence. But instead of just shouting out hoots and noises I for some reason decide to just speak loudly in complete sentences, announcing exactly what I intend to do.

“Listen here, black bear,” I announced. “You are not getting my food. I am putting it away right now and I’m going to raise it up into a tree. So give up and go away. I’m getting my rope out right now. Yes, it does seem to be working in your favor that most of the taller trees here do not have branches that are the proper height, but I am determined to keep you from my food. Go away. Now.”

Eventually, I managed to pathetically hang my stuff sack of crude nourishment about seven feet in the air, up against the trunk of the tree, where any self-respecting bear could reach it as easily as a 5-year-old kid could climb a kitchen counter to reach a cookie jar on the top cupboard shelf.

And then I stood there and waited. And waited.

The large mammal sounds were still there, but not getting any closer. The sun was going down and it was about to get dark. What should I do? Climb into my tent and blindly listen to what is certainly a bear trudging around my campsite?

For some moronic reason, I decided I should grab my deer knife and go out and check things out. I wanted to put eyes on the enemy while there was daylight. So, still explaining out loud what I was doing, I clutched my weapon and headed into the brush.

“I’m just coming to get a look at you, ol’ boy. No reason to panic. Let’s all just be cool here.”

In a matter of seconds I found my large mammal. A moose was hanging out in the nearby swamp, not really interested at all in me, my incessant shouting or the delicious preserves left dangling at what would be close to mouth-height if Bullwinkle cared enough to lumber over and check it out.

So that’s pretty cool. I saw a moose on my first night alone on the trail. And I got to continue eating the food I brought for the rest of the trip.

The next morning is when I started to become concerned about something I had figured out the day before. I was deep in the woods without a water purifier and performing heavy exercise hiking with a 40-or-so-lb. backpack. The two tiny water bottles I brought were almost empty and I wasn’t drinking anywhere near as much as I should. I needed to get to town or find a fellow hiker who might be smarter than I am.

Back then, part of the trail near Hovland wasn’t built, so hikers had to hoof down Highway 16 into town and walk Highway 61 a couple miles until the trail resumed. So I had to pass though town whether I needed water or not. In this case, however, town consisted of the Hovland General Store and pretty much nothing else. But that would do the job, right?

When I reached the Highway 16 trailhead I noticed a parked car. Almost immediately, another car pulled up. A middle-aged couple got out and placed a bottle of water under the parked car. They explained to me that their son and daughter-in-law (or maybe it was daughter and son-in-law) were going to be coming off the trail that afternoon and would be thirsty. Apparently I wasn’t the only one out there without a purifier.

That bottle of water looked pretty refreshing. I couldn’t help but consider stealing it. It wouldn’t have been a big deal, really. The other hikers had a car parked right there. The general store was only two miles up the road. But it wasn’t like I was going to die without stealing water, and besides, I repeat, the general store was only two miles up the road. No need to resort to thievery.

I chatted with the couple at the trailhead a bit longer and when I mentioned I would be hiking the highway to town they offered me a ride. I accepted.

During the ride, I learned the couple was related to Brooks Anderson, the Lutheran minister from Duluth who at the time was in prison serving a three-month sentence for trespassing while demonstrating against the Army’s School of the Americas at Fort Benning. I told them they should be proud of Brooks. They said they were and expressed shock that a judge could possibly consider him a threat to society. I told them nothing is more threatening to a government than a citizen who has courage.

The Andersons dropped me off in front of the store and went on their way. They had given me a warm feeling. I didn’t mention my thirst to them, knowing I was almost to the store. And talking with them kept me from thinking about it as much as when I was hiking and sweating.

I set my pack down outside the store and walked in carrying my two plastic canteens. I approached the woman behind the counter and asked where I would find a faucet where I could fill up.

“The owner has a policy against that and he’s here and I don’t want to argue with him,” she told me.

I told her, “I have a policy, too.” And I left.

I suppose if I had Brooks Anderson’s brand of courage I’d have argued with the owner or staged a thirst protest at the register. I’m Paul Lundgren, though, and Paul Lundgren has to be Paul Lundgren. So I decided I didn’t even want to look at the owner, I certainly didn’t want to buy bottled water at his store, and clearly my job is to badmouth him on the internet 16 years later, despite having never actually met him. I’m not proud of it, it’s just who I am.

Judge C. R. Magney State Park wasn’t far from the store, and I found plenty of good drinking water there.

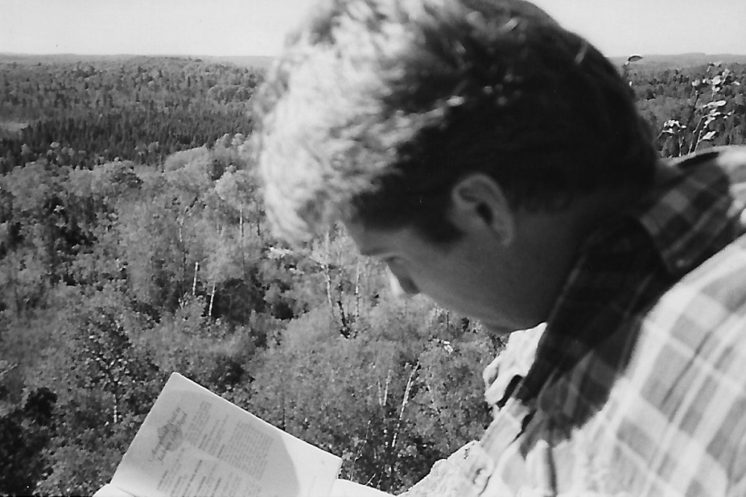

It’s difficult to remember details of all the beautiful scenery and chats with passing strangers on the trail after all these years. I think the photo above, the last one of the trip, is from the first day of hiking, shot selfie-style because the camera had no timer, at a place called “Hellacious Overlook,” but I could be wrong. A couple of old newspaper columns I wrote helped me pull together the Hovland General Store incident. Scrambling to get my food into a tree to save it from a bear who turned out to be a moose is still pretty vivid in my memory, though.

The only general note about the scenery I kept from 2000 begins by emphasizing the grotesque. It was written at one of my favorite spots, the top of Pincushion Mountain:

The natural beauty of wilderness is comprised of many ugly things. Dead trees, rabbit turds, muddy swamps, maggot-infested deer carcasses — genuinely nasty stuff. These sights all serve as an important reminder to human beings. When a loved one dies, we are sad, angry and torn apart. When thousands of people die in another country, we change the channel. When a bear devours a fish, that’s business as usual. Life is so terrible and wonderful at once, the only way you can really make sense of it is to climb on top and look down.

My next three nights on the trail were spent at Kadunce River, Grand Maris Municipal Campground and finally Cascade River State Park, which I decided would be a great place to continue my adventure in 2001. I used the payphone at the park to call my parents and request a ride the next morning. There were payphones back then.

“Sixteen Years on the Superior Hiking Trail” Index

Part one: Introduction

Part two: Preparations

Part three: Swamp River to Cascade River

Part four: Cascade River to Temperance River

Part five: Nonchalance

Part six: Temperance River to West Branch Bar in Finland

Part seven: Duluth Sections

Part eight: Finland to Silver Bay

Part nine: Silver Bay to Split Rock State Park

Part ten: Two Harbors Vicinity

Part eleven: Leaves, Needles, Mud

Part twelve: Loss and Lost

Part thirteen: The Double Finish

Part fourteen: Ely’s Peak Loop

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments