Reflections on Race and Community-oriented Policing

This is going to begin in Milwaukee, pass through St. Paul, and end in Duluth.

This is going to begin in Milwaukee, pass through St. Paul, and end in Duluth.

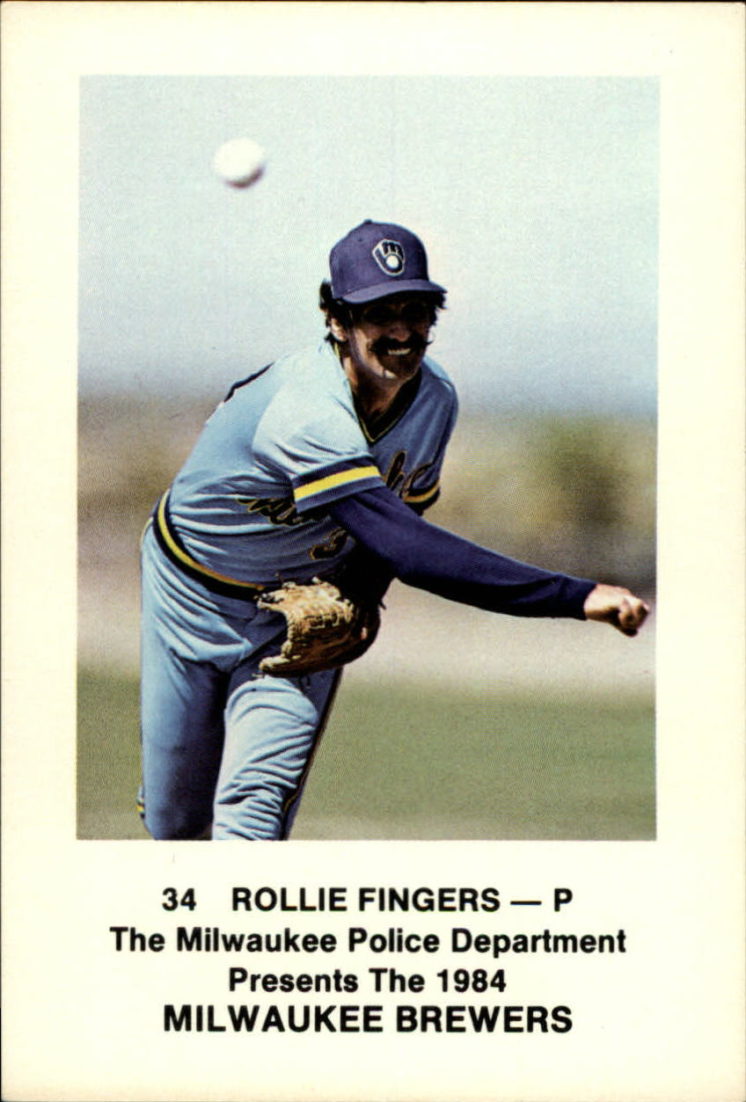

When I was a kid, the Milwaukee Police Department gave away baseball cards. The cards were printed for the police with the Milwaukee Brewers as the celebrities. Each officer carried two, and you had to talk to more than one officer over the summer to collect a full set. It was a great strategy for bringing families and police together. My favorite Brewer was Rollie Fingers, because he had a handlebar moustache. I didn’t know anything, any damn thing at all, about baseball.

The baseball cards were part of a “community-oriented policing” initiative. I was a kid; I barely understood what that meant, but I understood the problem it was meant to address.

In 1981, when I was nine, Ernest Lacy was arrested on suspicion of rape in Milwaukee. According to an account in The New York Times, Lacy was taken into a police van, where “two of the officers then held his legs down by placing their feet on his legs, and a third officer placed his knee between Mr. Lacy’s shoulder blades, forcing him to lie face down with his left cheek pinned to the ground. … Then, one of the policemen pulled Mr. Lacy’s arms up beyond his shoulder blades and over his ears [with] one violent, convulsive seizure and then the black man was absolutely still. … [T]he extension of Mr. Lacy’s arms toward his head interfered with the flow of oxygen to his lungs. … [T]his was fatal.” Lacy was taken alive into a police van and was removed dead, a victim of police brutality.

(Another man was convicted of the rape, if that matters to anyone reading this. It shouldn’t for Ernest Lacy any more than it did for Clayton, Jackson and McGhie.)

Ernest Lacy was African-American at a time when the Milwaukee police had an explicitly racist organizational culture. For example, Police Chief Harold Breier claimed that desegregation and school busing caused crime. “We have bused crime all over the city,” he told editorial writers, suggesting the South Side, a largely white residential neighborhood, “now has black crime.” Racism ran from the chief into the streets.

I remember almost nothing about being nine. I don’t remember what grade I was in, or what TV shows I watched on Saturday mornings. I remember Ernest Lacy. I remember thinking: police gave out baseball cards. They weren’t supposed to kill people they pick up on the street.

* * *

In May, 1991, when I was 19, police arrested Jeffrey Dahmer. My friends and I piled into a car to go see the apartment where he killed people. We couldn’t get within two blocks of the site.

It was months later that we learned he could have been caught several weeks earlier, if the cops had cared one whit about the welfare of a Laotian boy. Two Milwaukee policemen returned “a fleeing, dazed and naked 14-year old Laotian boy [Konerak Sinthasomphone] to [Jeffery] Dahmer`s apartment, where he was killed and dismembered a short time later.” Police officers were recorded making homophobic and racist comments on police radio after they left.

My first impulse was to shriek inside at the injustice.

My second was to wonder: because I was white, would they have helped me? Or, accepting Dahmer’s story, that I was gay, would they have left me to die, too? And how messed up is it that my 19-year-old self would wonder what it would take for the police not to leave me to die?

And how many of my friends lived with that feeling every day?

* * *

I’m reading about Philando Castile, about the shooting in Falcon Heights, a suburb two hours away from Duluth, just north of St. Paul, where I lived for ten years. I’m thinking about this in the context of Ferguson, of Black Lives Matter.

The violence is not new, nor is the racism (nor for that matter is homophobia). Police violence has been present for all of my forty years.

What is new is the video.

* * *

I think about my home for the past decade, Duluth. I feel optimism and hope. Former Duluth Police Chief Gordon Ramsay talked about community-oriented policing in his blog and in the Budgeteer News. A visit to the Duluth Police Department web page shows current Chief Mike Tusken sees the community as a partner. Community-oriented policing might be part of what prevents these tragedies in Duluth.

“Community oriented policing” means working against the sometimes-racist, sometimes-homophobic culture of policing by making sure that police encounter people of color and LGBTQ people as people.

As Paul J. Hirschfield notes in Lethal Policing: Making Sense of American Exceptionalism: “police have killed people after allegedly mistaking such objects as wallets, phones, candy bars, spray nozzles, and Wii remotes for guns … because hesitation in the event that the threat is real could prove fatal to the officer.”

We need to remind police they are encountering people, not threats, in most circumstances. In those officers for whom racism and homophobia play a role in defining a threat, we have special work to teach them that people of color and LGBTQ people are people first.

We need to shriek at the injustice, but shrieking at someone embedded in a racist, homophobic culture is only one path toward action. Working toward community-oriented policing as more than just a “liaison” position in a department but a relationship between all patrol policemen and all members of their community is another. Make sure police understand their community includes people who are different from them, and some who aren’t that different, after all. This is the kind of work (of making police part of their communities, rather than outsiders policing their communities) that never stops.

When the person stopped for a taillight violation is not perceived as a threat by virtue of being different, the script will change just a little. Perhaps enough to save lives.

* * *

Maybe an end to police violence will come because we are more aware. The police can no longer be as brazen as they were in my youth, in covering their tracks and denying their culpability.

In 1983, Milwaukee’s then-Police Chief Harold Breier “sent high-ranking officers to the homes of about 40 citizens who did not like Police Department operations. He said he had sent the officers “to straighten out the thinking” of people who were “misinformed.”

Too many are “misinformed” today, on video, for those kinds of intimidation tactics to work. Too many people know, too many people are willing to take to the streets to protest, and I hope, enough of us are willing to partner with the police to move forward.

(This essay is dedicated to S. and K.)

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

2 Comments

Jana Studelska

about 9 years agoDavid Beard

about 9 years ago