Down Town

“I’m from New Jersey, I don’t expect too much

“I’m from New Jersey, I don’t expect too much

If the world ended today I would adjust.”

–John Gorka

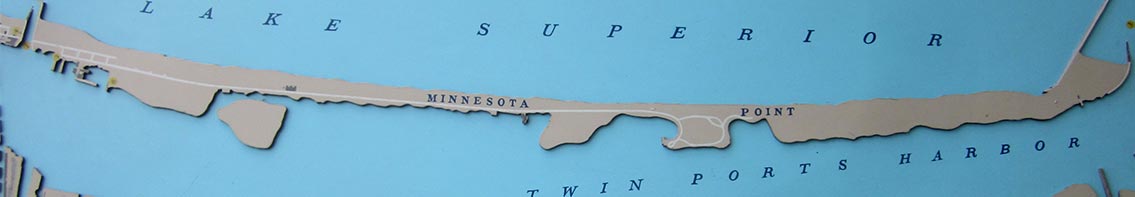

New York, New Jersey. San Francisco, Oakland. Duluth and Soup Town. The Deep North, top of the map, and shallow end of the gene pool. Ugly sister-city. Can you feel the gravitational pull of the swamp it was built on? This force that bends us, slouching like the lowland willows. That drives water, beer and whiskey to seek the lower ground. Rains and fortunes falling, down and down. The banker’s son becomes a biker. The executive’s boy delivers pizza and sells dope well into adulthood. Sociologists call this “regression toward the mean.” Or maybe the swamp is pulling them. Down.

Of course the place tosses off an astronaut or Nobel winner once in a while. But folks mostly seem to understand they were born in second-place, and second place, as we know, is first loser. You get used to it. It helps to have negative role-models. Don’t do what he did. Look out for that. Rest in peace.

Let me tell you about our long-ago, analog ways. At first there were no Frisbees and no convenience stores. Elm trees lined the streets and a union job could float a family. This second-place golden-age exists only beneath a glassy snow-globe sky, held in the palm of my hand. Memories bend beneath, or ricochet off my missile-defense shield composed of pure nostalgia. Cracks will appear soon enough, but for now the grownups’ problems strike glancing blows, ephemeral as the light of the television, and no more consequential.

We had it all, really. I swear it wasn’t as flat back then. There were more gullies, more creeks, more crooked places. I loved them so. They’re gone. We had parks and fields and bums’ jungles. Places to cast our spoons and endless trees to climb. Strangers’ doors were open to anyone under four feet tall. A transistor radio swung on its strap as I rode my Sting Ray to the bay. “Sugar Sugar, Honey Honey.”

Cracks in the sky soon appeared. The boom times were ebbing as our hormones reached high tide. The oil embargo dovetailed with the end of the war. We pulled out of Viet Nam and rock-and-roll went to hell. All that rebellion was squandered in a beer-hippy rampage by rebels without a clue. “Free Bird!”

Through the cracks, with a wind from the south, you could smell the refinery, where an eternal flame burned excess gasses from a tower visible down our avenue. On rare occasions the southern clouds would reflect the lovely, rosy glow of an out-of-control industrial blaze. “Fire at the refinery,” we’d say.

From Duluth you look across the big lake and into blue Wisconsin. From Superior you look at Duluth. You know the lake is there only when the maritime wind howls from that direction. You know the trains are there, because they idle and couple through the night. Those trains, with all that heavy metal, forever in the way, would be made to serve our needs, and our needs were simple: kicks. We started young, and small, flattening pennies beneath their wheels. Made whistles from pieces of metal strapping found along the tracks. Moved on to hopping them, going, of course, nowhere in particular. We ramped it up to jogging along the running boards on top and leaping from car to car. Then someone figured out how the crossing signals worked. If you held a metal bar across the tracks a block away, it closed an electrical circuit and lights would flash, bells would ring, and the crossing-guard arms would lower, blocking traffic. You could let the cars line up for a while, then release them, one by one.

A trio of trees on our corner lot were the biggest for blocks around. Two unclimbable cottonwoods flanked an enormous willow. As a city crew swept up the last of the elms my father told them to take out the giant nearest the house, afraid that it might fall. So we lost a tree that shaded half the yard, and more than half of childhood. Soon after, the north wind felled the two survivors. Down. I don’t know if their death pact was based on physics or sylvan sympathy, or if my father was prescient in his fears for the house, but the world was flatter, and not so green, and this seemed to tell the future.

After a couple stints in Minneapolis I moved all the way to Duluth. Consider my humble origins — I’m easily impressed. Before the Bong Bridge existed, before buses ran to Superior on Sundays, there was a railroad swing bridge that crossed the river beneath the span for the highway. I needed to get across for Easter dinner at my parents’ place, so I started walking the tracks. I made it to the middle of the river before the harbor started spinning, and the bridge opened up. There it stood, not a ship to be seen, and I was stranded between the fraternal twin ports. With hat in hand I climbed the stairs to the control room. A blue-eyed man in a white T-shirt seemed surprised to see me. I confessed. I told him about Easter dinner. About the paucity of bus service. He threw some levers, and the harbor began spinning on its axis once more. “Wait,” he said, as I turned toward the stairs, and he spoke those words which must be spoken to all who cross this river:

“What time you coming back?”

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

4 Comments

treepeople

about 9 years agoJana Studelska

about 9 years agoBecky Sturtevant

about 9 years agoMichelle Rowley

about 9 years ago