Archetypes in Wrestling: Reflections on Recent Matches at Wessman Arena

I spent last Saturday night thinking and rethinking about cultural archetypes through the most popular form of American theater, the wrestling show.

I spent last Saturday night thinking and rethinking about cultural archetypes through the most popular form of American theater, the wrestling show.

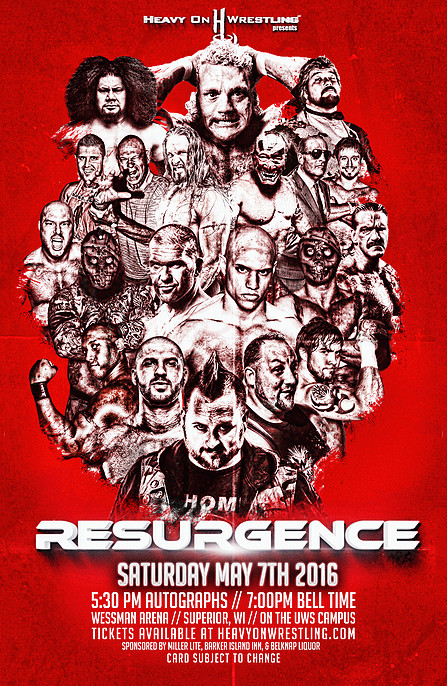

Heavy on Wrestling, a Duluth-based promotion, has organized numerous cards over the past decade at casinos and entertainment centers throughout the region. Last week’s event at Wessman Arena was intergenerational. Baron von Raschke, who started wrestling in 1966, served as the “commissioner.” For those a bit younger, who remember wrestling on network TV, “The Million Dollar Man,” Ted DiBiase and Eugene were present; DiBiase signed autographs and Eugene wrestled Minnesota wrestling mainstay Mitch Paradise.

If you thought wrestling was something that only happened on cable TV, you are missing out. There are more than a half-dozen wrestling promotions in Minnesota running shows throughout the state. To learn more, follow the work of Razzling Rick.

So how were the matches?

The opener was a throwback. Daivari grabbed the mic, spoke what I took to be Farsi, then translated for “the stupid Americans.” (And let’s be honest — I’m only guessing it’s Farsi because he said he was Iranian — the PhD holder in the bleachers accepts that he’s a stupid American.) Preserving our honor, Matt Winchester, the Beer City Bruiser, trounced him. (Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the 1980s. Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the post-9/11 era. Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the Trump campaign. Oh, forget it. It’s not flashbacks. It’s a permanent condition of living in the United States.)

The opener was a throwback. Daivari grabbed the mic, spoke what I took to be Farsi, then translated for “the stupid Americans.” (And let’s be honest — I’m only guessing it’s Farsi because he said he was Iranian — the PhD holder in the bleachers accepts that he’s a stupid American.) Preserving our honor, Matt Winchester, the Beer City Bruiser, trounced him. (Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the 1980s. Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the post-9/11 era. Oh, the flashbacks to the jingoistic nationalism of the Trump campaign. Oh, forget it. It’s not flashbacks. It’s a permanent condition of living in the United States.)

But there were alternatives to the traditional hypermasculinity of professional wrestling in last week’s show. Men a third his age still cringe at the threat of the Claw from the Baron, which does something to upset our assumptions about age (though maybe not about male power).

Eugene presents a wrestling persona who adores children and who would prefer to be friendly, rather that hyperaggressive. In a key moment of his match with Mitch Paradise, as Paradise was building momentum, bouncing himself back and forth between the east-west ropes of the ring, Eugene began bouncing himself back and forth between the north-south ropes. As a result, they did not smash into each other. It was a brilliant move, defying our expectations (that the men would crash and the strongest would remain standing). A sense of play is essential in a hyperaggressive world.

In Minnesota, hypermasculinity is being questioned by the work of Terrance Griep, the Spider-Baby, the first openly gay, inside and outside the ring, wrestler. Griep establishes that wrestling is not just for one form of masculinity. But maybe more to the point, he’s an accomplished actor in the ring; he engages real performance. Griep is bald, and I remember how convincingly he tried to argue with a referee once, at a show in a parking lot outside an American Legion, that his opponent should be disqualified for pulling his hair.

It is theater I watch when I go to see wrestling, and it’s the most collaborative form of theater. People bring signs — one fan brought a dry erase board — and the “babyfaces” bask in adulation while a few of the “heels” go into the crowd to rip up signs that mock them. The crowd chants to support favorite wrestlers. The heels spit their bottles of water all over their opponents and the audience in a fine spray.

Most of us in the arena are actors in this play. The wrestlers are acting: pretending that the outcome is not predetermined, pretending that they do now know what move will “finish” the loser, so that the loser will know not to kick out of the three-count. We, in the bleachers, are like theatergoers who believe that rooting for Laertes might have any effect on his duel with Hamlet.

And wrestling hurts, it surely does — a predetermined outcome does not make a fall from seven feet any less painful, and the consequences can be tragic. But it is theater, too. Like a theatregoer who pretends that a red kerchief is blood, we pretend not to notice that every time a wrestler punches an opponent he slams his feet against the mat. The mat is engineered to make a massive noise when slammed. Sound effects.

I like wrestling because I think the wrestlers, the ring announcer, the referee, and the fans are really one massive theater company, creating this event together.

There were so many children at this match. Scratch that — so many young boys. The wrestlers loved interacting with them, and it was fun to watch the boys get so excited. At the same time, I’m a professional worrier. I worry, some, that the boys don’t realize it’s theater, not life. That they will internalize some of the worst lessons of wrestling: That you only have to listen to the rules, to the referee, if you want to. That the man who can make another man submit, or who can pound another man until he can’t get up, is the winner. That the only woman in the show was a “manager’s assistant,” and that’s normal.

I think about a segment of This American Life TV I watched recently, “Ask an Iraqi,” and the ways we send our Beer City Bruisers into the Middle East with cheers and paper signs, stupid Americans. I think to myself: How old should a young boy be before he’s taught that wrassling is theater — and that in very collaborative theater, even a small boy can shape the future. If we stop cheering for the Beer City Bruiser as he pins the Iranian, the promoter will find another gimmick. If we stop cheering for soldiers who occupy the Middle East on our behalf (because they are “protecting our freedom,” etc.), maybe our leaders will develop another foreign policy. It’s a long shot. I’d be willing to try.

If we teach the boys in the audience, whether they were nine years old or ninety, that just because someone in the front starts chanting “USA, USA,” we don’t need to chant, too… If we can teach the boys in the audience that we can boo both the “heel” who threatens the only woman in the match and the “face” who rescues her (because she doesn’t need either one of them, she’s fine on her own — though maybe she could stand a few sisters, in the next event)… If we can teach the boys in the audience that Eugene has the right idea, that you can refuse the script of hyperaggression, sometimes…

If we can teach the boys that our part in the participatory theater of wrestling can change the script for the next event, well, maybe, we can change the scripts of some other things, too.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments